The Modelling Relation

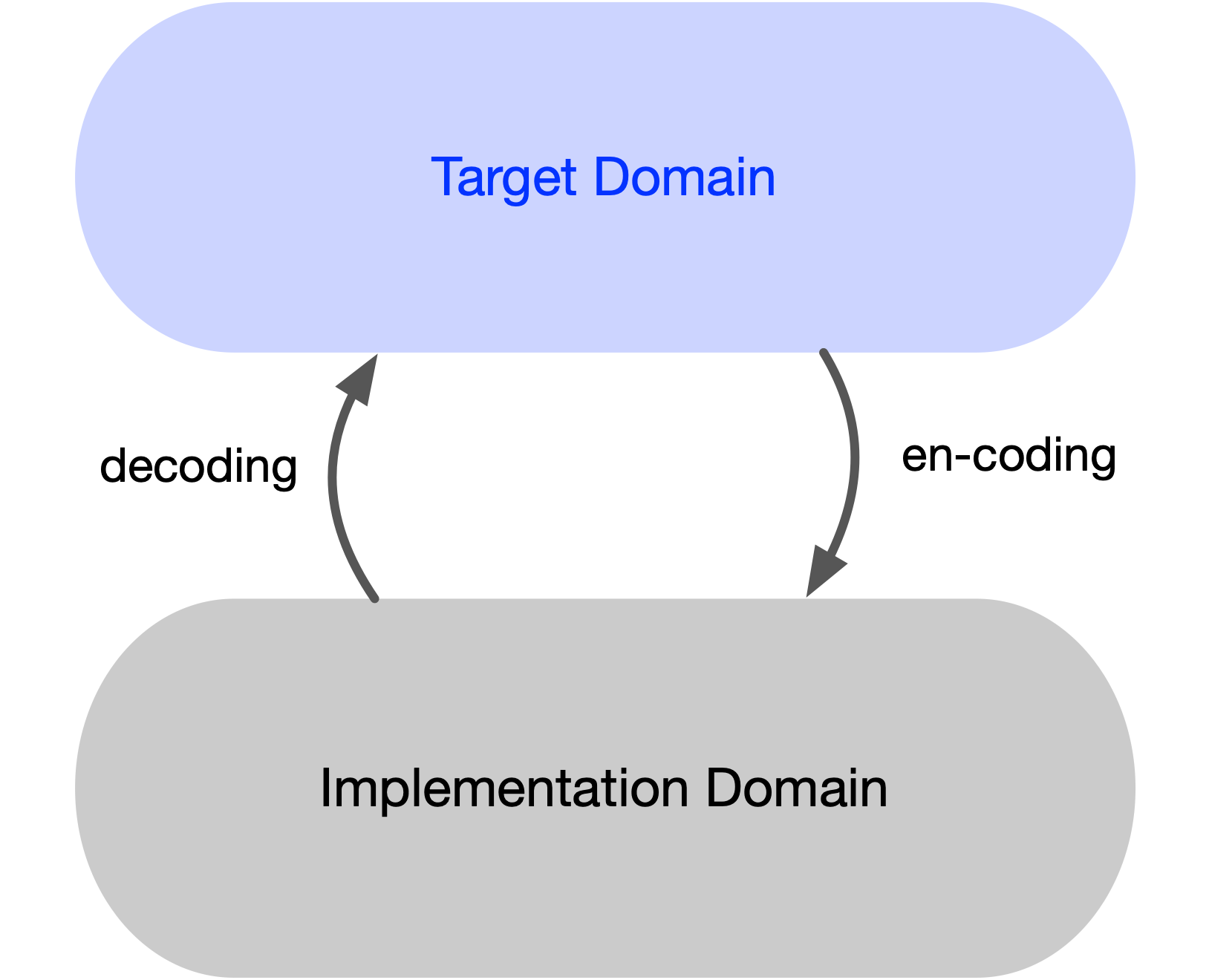

The modeling relation, however, is not limited to natural systems. It applies to any pair of systems where one serves as a model of the other.

Note that the formal system is something built to serve a purpose: to model another system (e.g., a natural system).

The system to be modeled (e.g. natural system) is given to us at the outset as the goal.

Hence we will call it the target system (instead of the natural system), and the formal system we build in order to model it will be called the implementation system. These terms describe the functional roles these two play in the modeling relation rather than their nature or origin.

We must also distinguish between a domain and a system built from its elements. When writing software, the domain consists of programming languages or hardware, which supply the building blocks. What we construct with these blocks is a system. For example, writing JavaScript code to compute the total cash value of a shopping cart takes place in the domain of JavaScript; the system being built is a summation function.

The nature of the available building blocks shapes the qualities of the resulting system. Thus, the implementation domain plays a decisive role in defining the character of its implementations: all systems built upon it inherit its structural constraints and affordances.

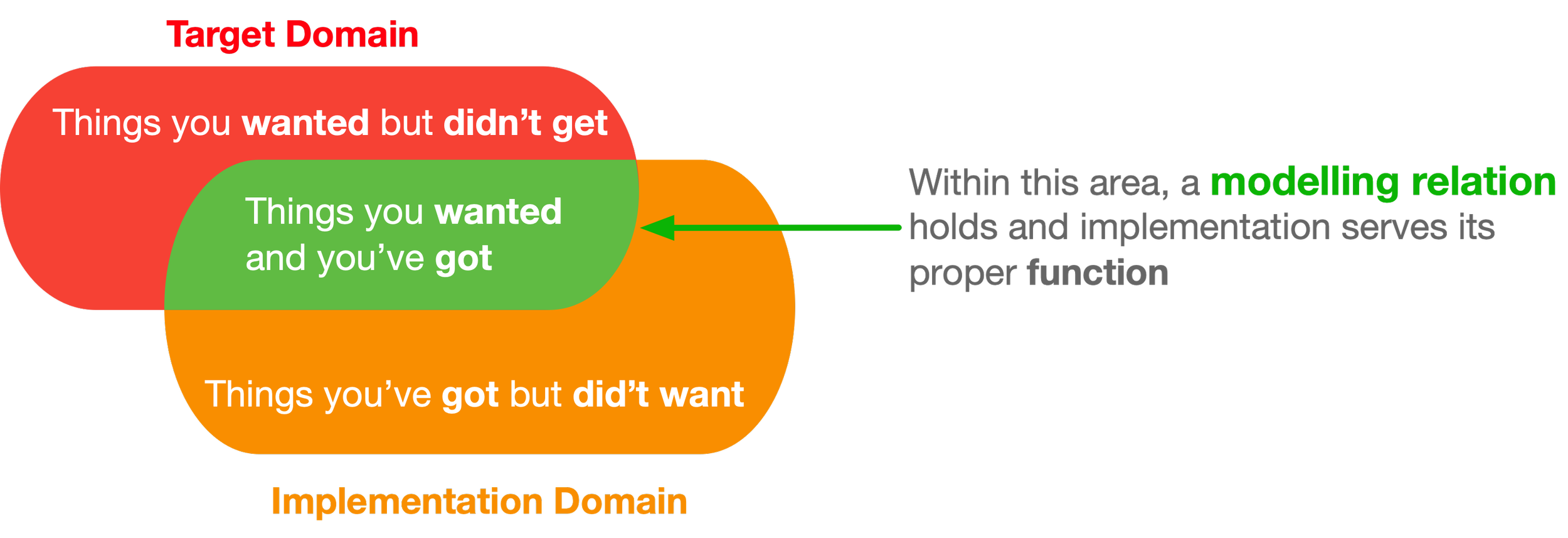

Our task, then, is to examine the relation between target and implementation domains in order to establish the conditions under which this relation qualifies as a true modeling relation. In theoretical terms, the presence of such a relation demonstrates that a theory succeeds in describing its target.

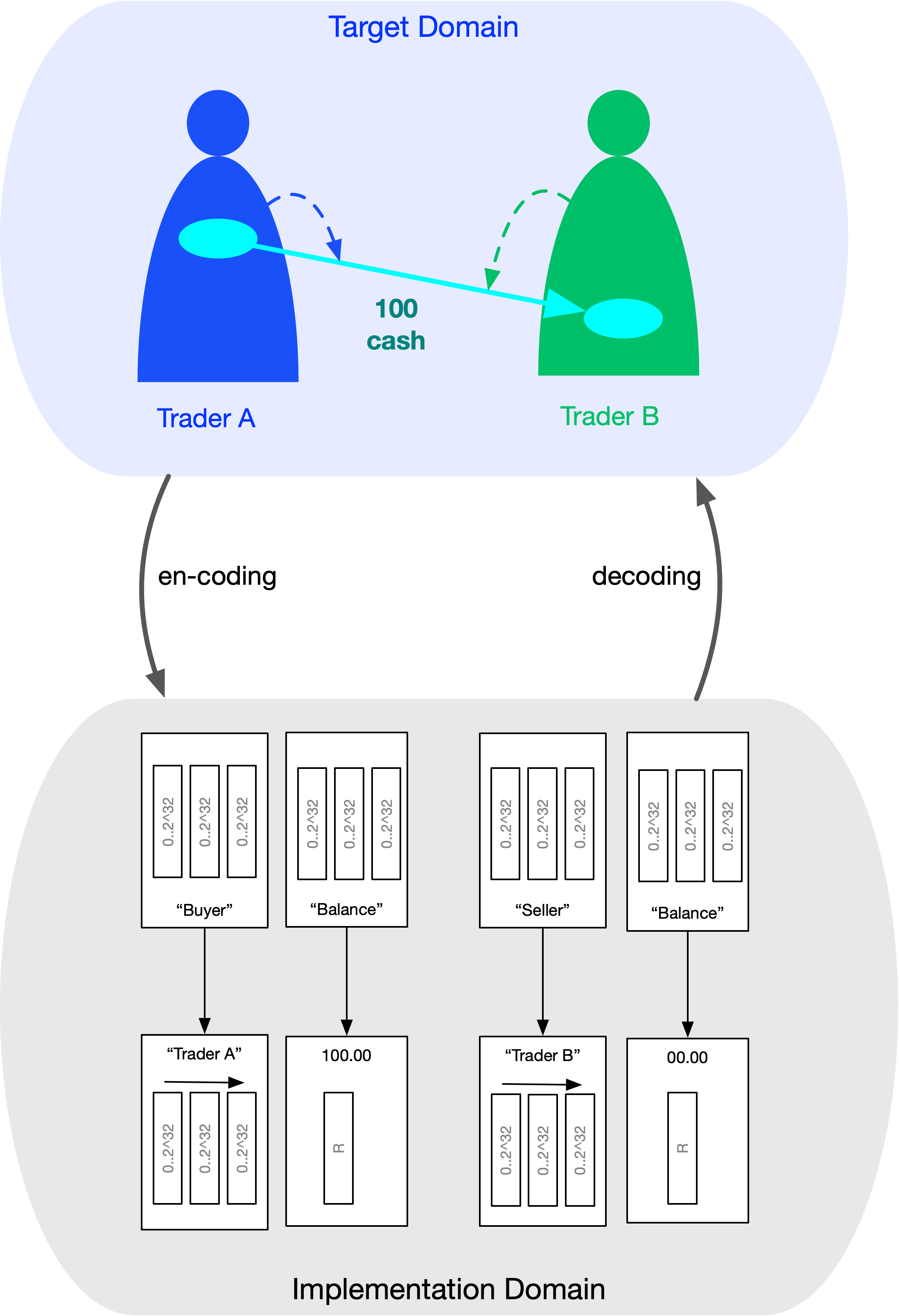

Following Rosen, we call the process of moving from target to implementation encoding, and the reverse—from implementation back to target—decoding. The target may be a domain, a system, or a natural process; the implementation may likewise be a domain, system, or formalization. Since our interest lies in software for business contexts, the term target domain may be read concretely as contract management or financial operations.

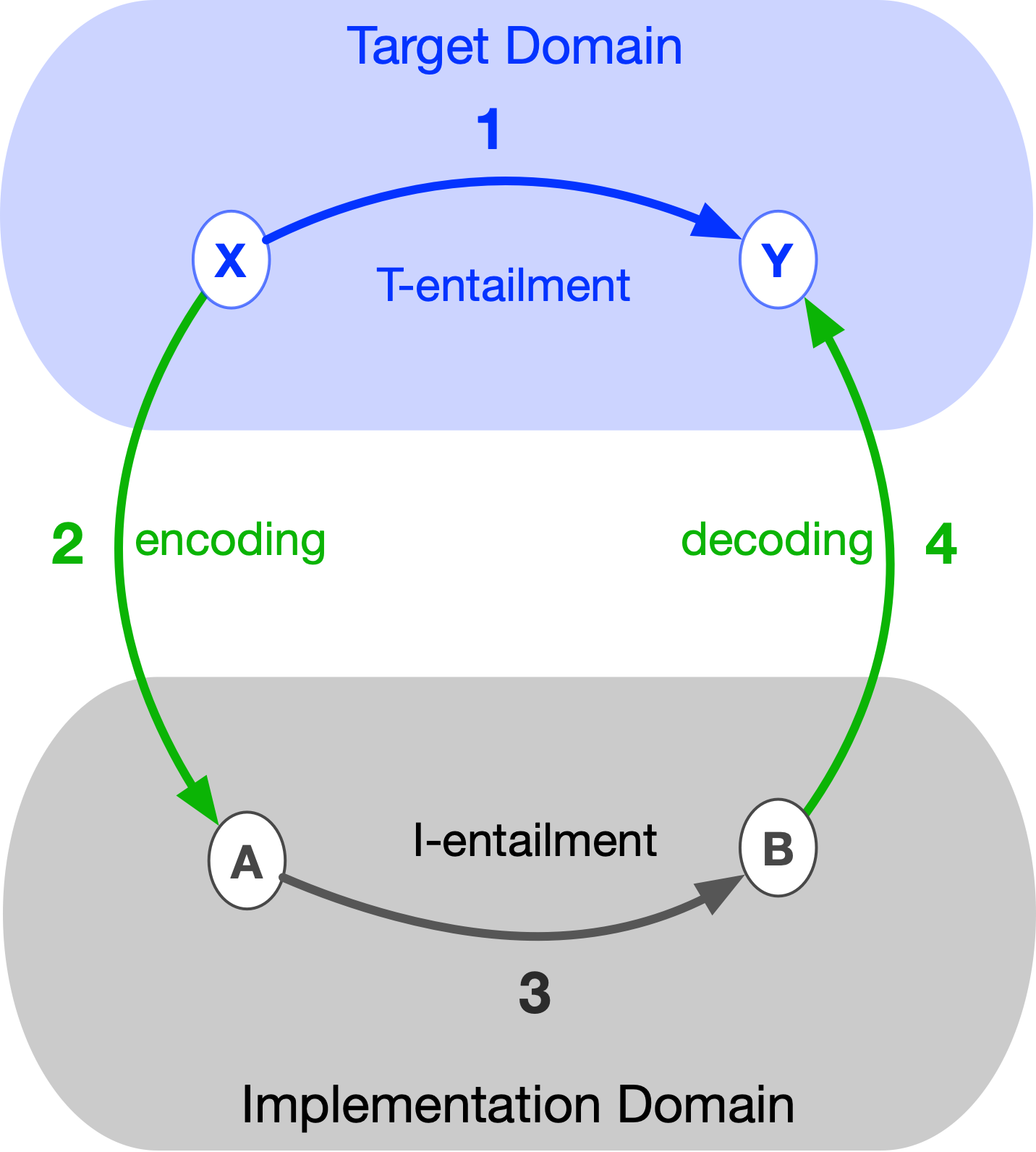

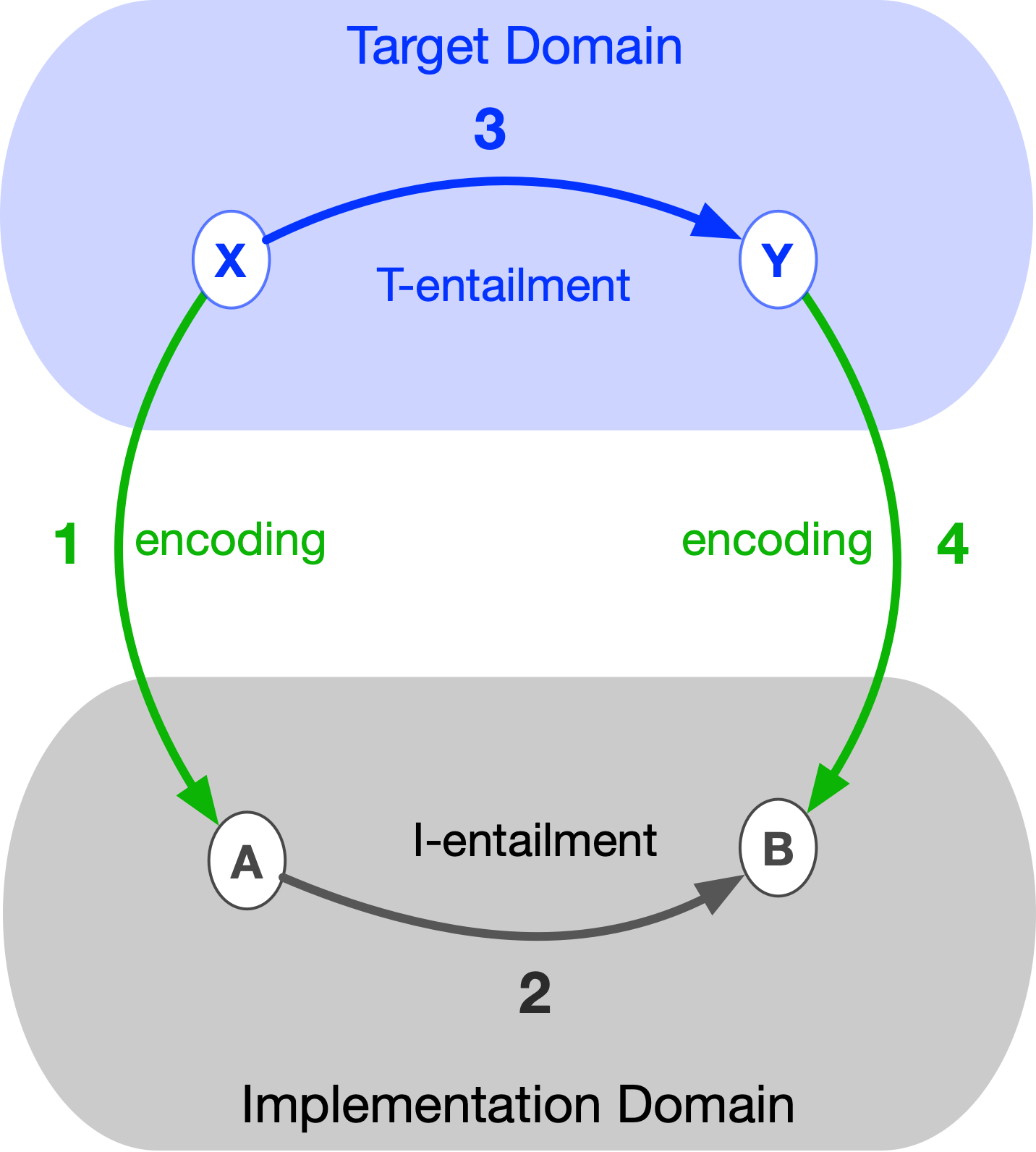

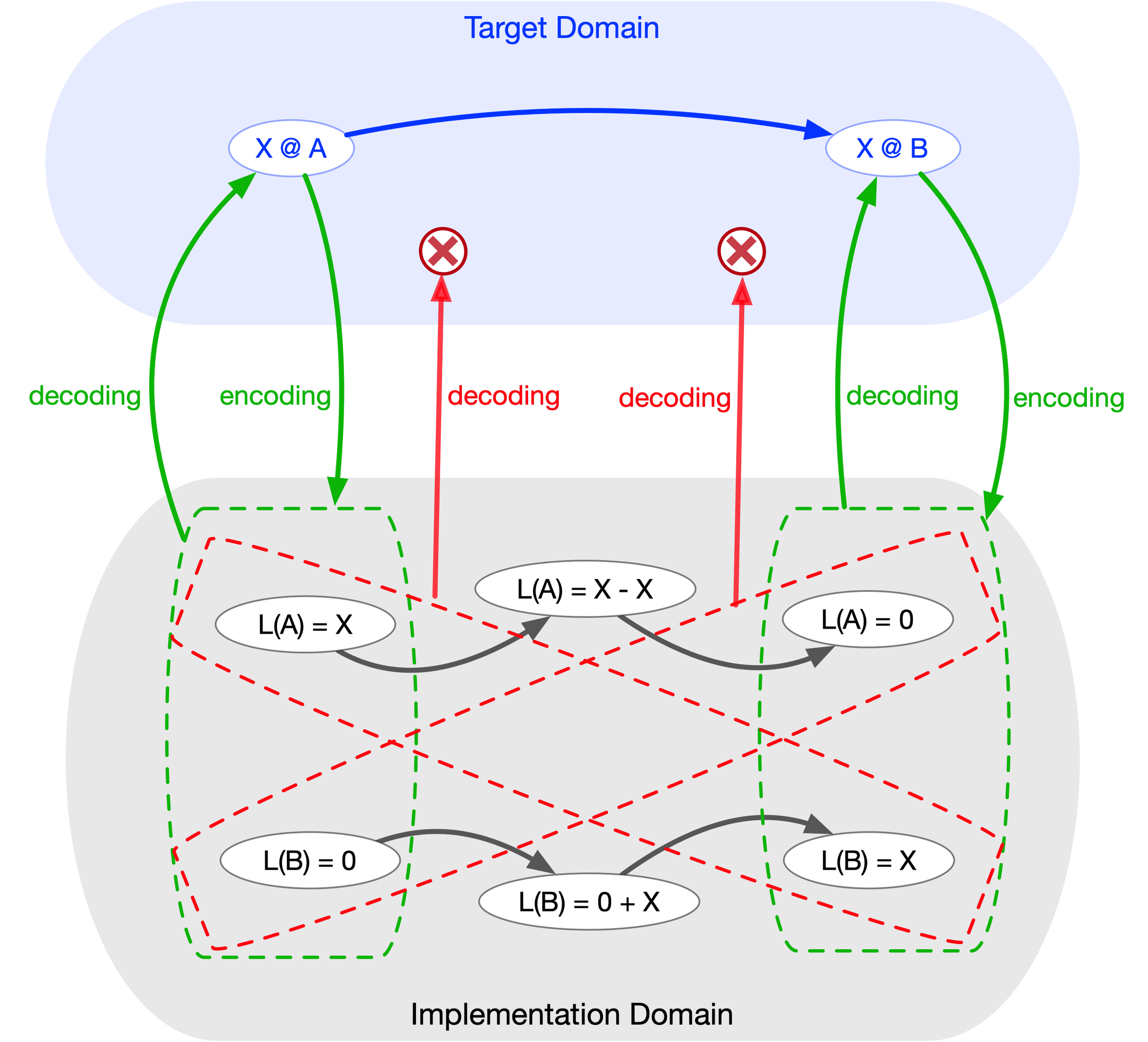

An implementation is said to be a model of a target if we obtain the same result by following path 1 as we do by following path 2 + 3 + 4 in the diagram on the left (or, in terms of a diagram on the right, this would be path 1 + 2 versus path 3 + 4). More precisely, an implementation models a target if the diagram formed by any composition of encoding/decoding arrows together with entailment arrows internal to each system commutes.

Suppose there is an entailment in the target (a T-entailment) where element X entails element Y (i.e., event X causes event Y). For example, consider a natural system consisting of a hot egg and a pot of cold water. Placing the egg in the pot triggers the T-entailment: the interaction between egg and water, which cools the egg. Here, X denotes the initial state of the egg and water, while Y denotes their state after interaction.

We can build an implementation (a formalization) to model this target. First, we encode X into A. Then we apply an entailment A → B within the implementation (an I-entailment, a rule of inference). Finally, we decode B back into Y in the target. In our example, the first step is measuring the temperature of the hot egg and the cold water before immersion—this measurement constitutes the encoding of X into A.

The second step uses the inferential machinery of the implementation (I-entailments) to calculate the expected equilibrium temperature of the egg and water.

Because a temperature value cannot be decoded directly into a physical object, we reverse the final arrow: instead of decoding, we perform another encoding (as shown in the diagram on the right). The last step is to measure the actual temperature of the egg after equilibrium is reached. If the implementation correctly reproduces the behavior of the target with respect to parameters A and B, then the measurement of Y coincides with B. In that case, the diagram commutes, and the implementation successfully models (that aspect of) the target.

Since modeling the target is the very reason for constructing an implementation, if the implementation fails to stand in a modeling relation to the target, it must be considered defective—because it did not fulfill its purpose.

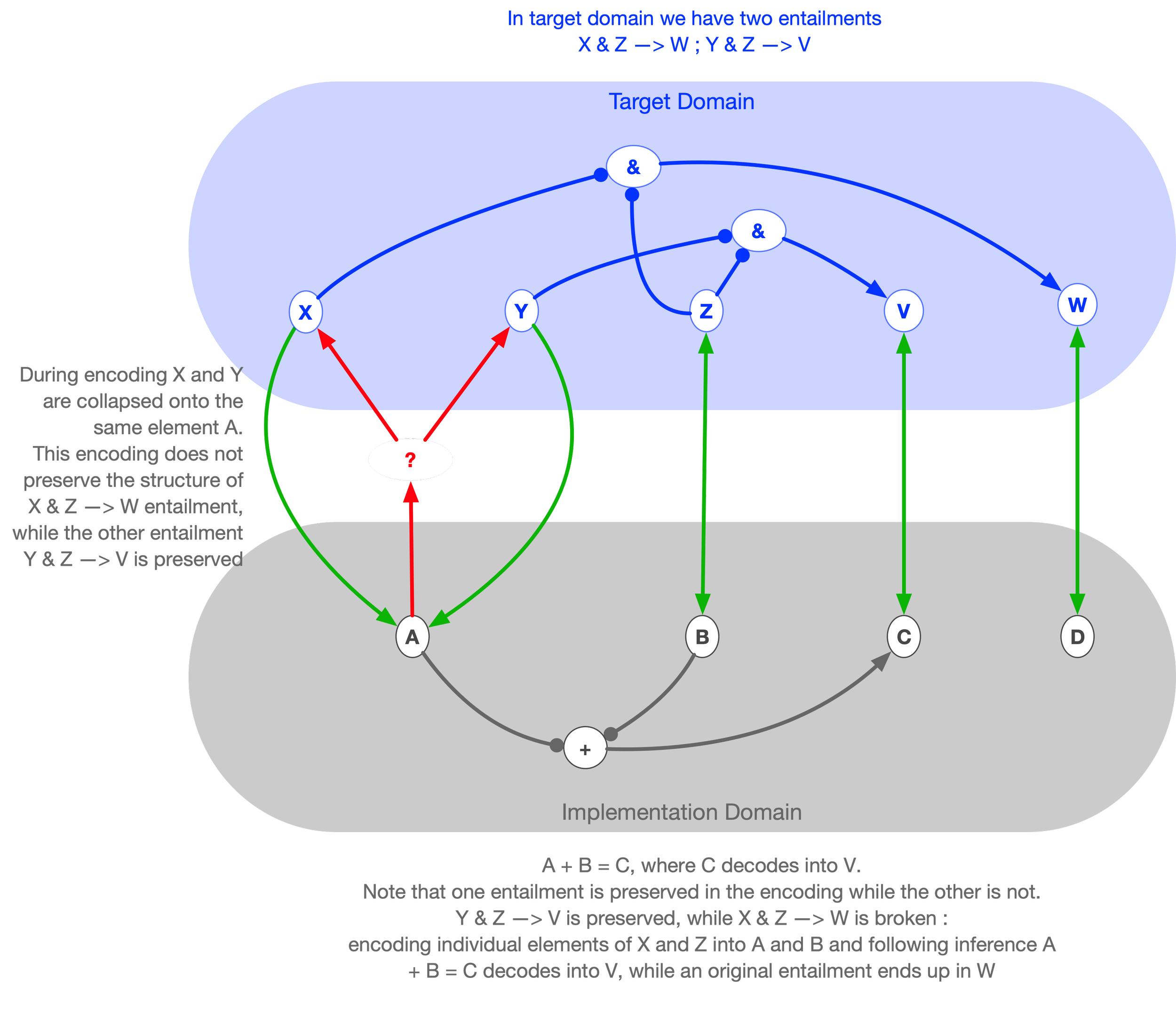

In software development practice, whether an implementation models a target depends on what we designate as the target—i.e., which subsystem of the phenomena we extract as the target to be modeled. The same piece of software may stand in a modeling relation to one target subsystem while failing to do so for another. In other words, a piece of software can be a valid implementation for some entailments of the target domain while being entirely defective for others.

Incommensurability Between Domains

Mathematical interpretation of the modelling relation

Mathematical interpretation of the modelling relation is given by a notion of a natural transformation of category theory: the T-entailments are functors of the target domain category, while I-entailments are functors of the implementation domain category.

Suppose that we have encoded functorial images of target category into functorial images of the implementation category. These encodings constitute morphisms in the higher level category, and the totality of these morphisms constitutes a natural transformation.

In other words, with modelling relation we have commensurability of inferential structure of two domains.

When building software, we are building it to serve some function, and in rich business domains such as trade processing, this function is to model the domain of financial operations, which existed before computers were invented and are conceptually independent of them. Thus, we view software as the implementation (formalisation), whose raison d’être is to be a model of the target. In other words, how well software serves its function depends on whether it stands in a modeling relation to the target domain.

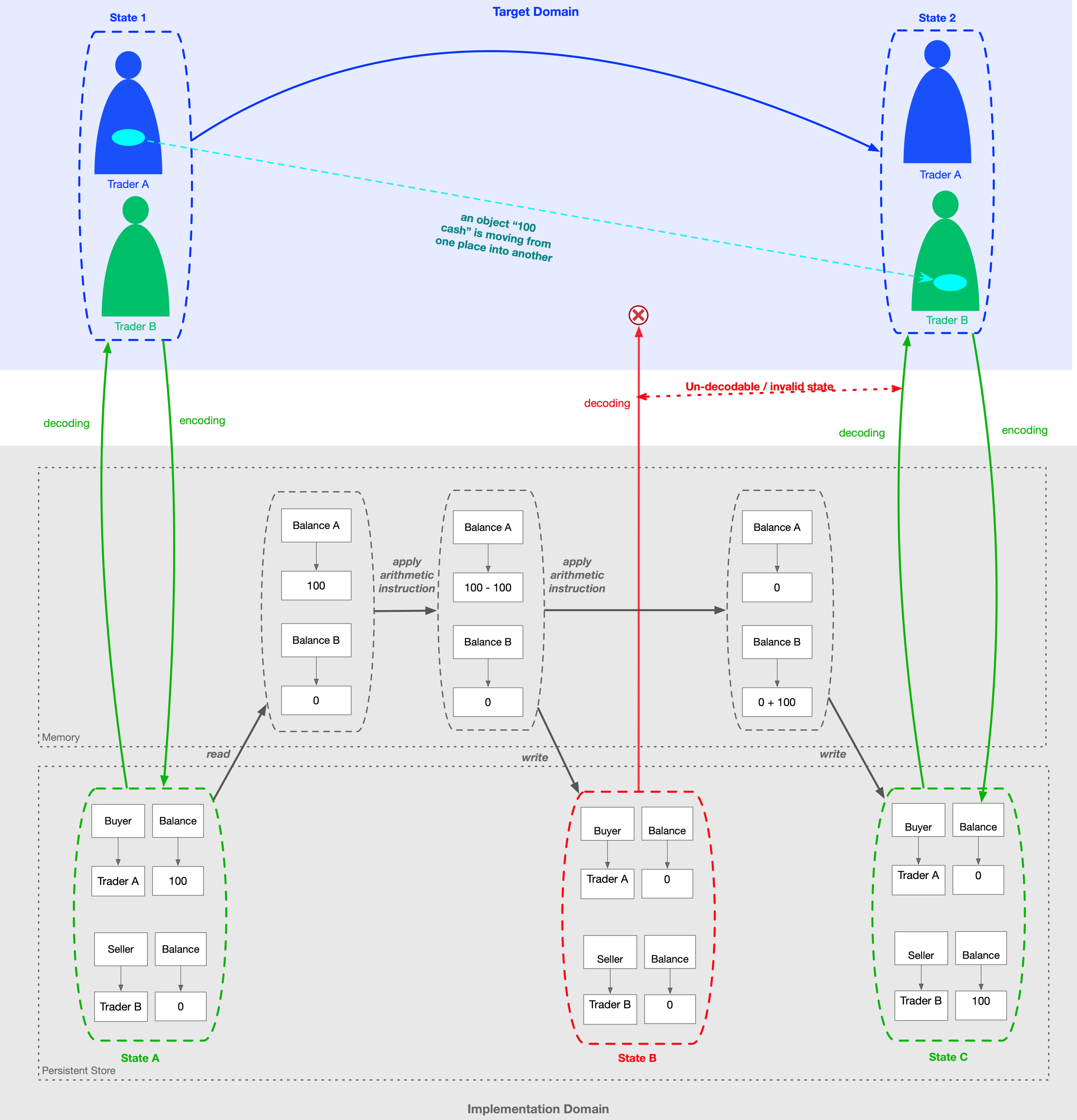

The modeling relation can be applied to implement a simple movement of cash in software—for example, as part of a financial transaction from a buyer to a seller.

The implementation domain will be that of computers and programming languages (such as Java, Go, C, etc.) built on top of them. The elements of the implementation domain are memory cells and the values stored within them, while entailments are the sequence of instructions or subroutine calls (regardless of how these foundational elements are wrapped into classes, objects, or functions at the programming-language level).

The target domain is the physical world, where a physical object—the cash—can move from one place (the buyer) to another (the seller).

The most important point is that these are two different domains, each with its own intrinsic structure (or constraints), and there is no one-to-one correspondence between them.

To model the financial operation of cash movement, we have to encode it into the elements of the implementation domain. The most fundamental issue here is the absence of space-time topology in computers, which leads to the loss of the notion of a continuous trajectory of an object.

In the real world, an object moving from place A to place B cannot be in two places at the same time, nor can it be nowhere.

But in programming languages, where there is no space-time—only independent memory cells with stored values—that constraint is absent.

Thus, encoding a financial transaction (credits or debits) loses this constraint and effectively decouples being in place A from being in place B. Again, the reason is that what is given to us for free in the target domain (spacetime topology) is absent in the implementation domain.

Breaking wholes into parts and reconstructing

Things themselves—the noumena, as Kant calls them—are inherently unknowable except through the perceptions they elicit in us. What we observe are phenomena, which are themselves shaped, by our perceptual apparatus (which, of course, also exists partly within the ambience). Thus, to know things, we require a mediator—our perceptual system or a scientific theory.

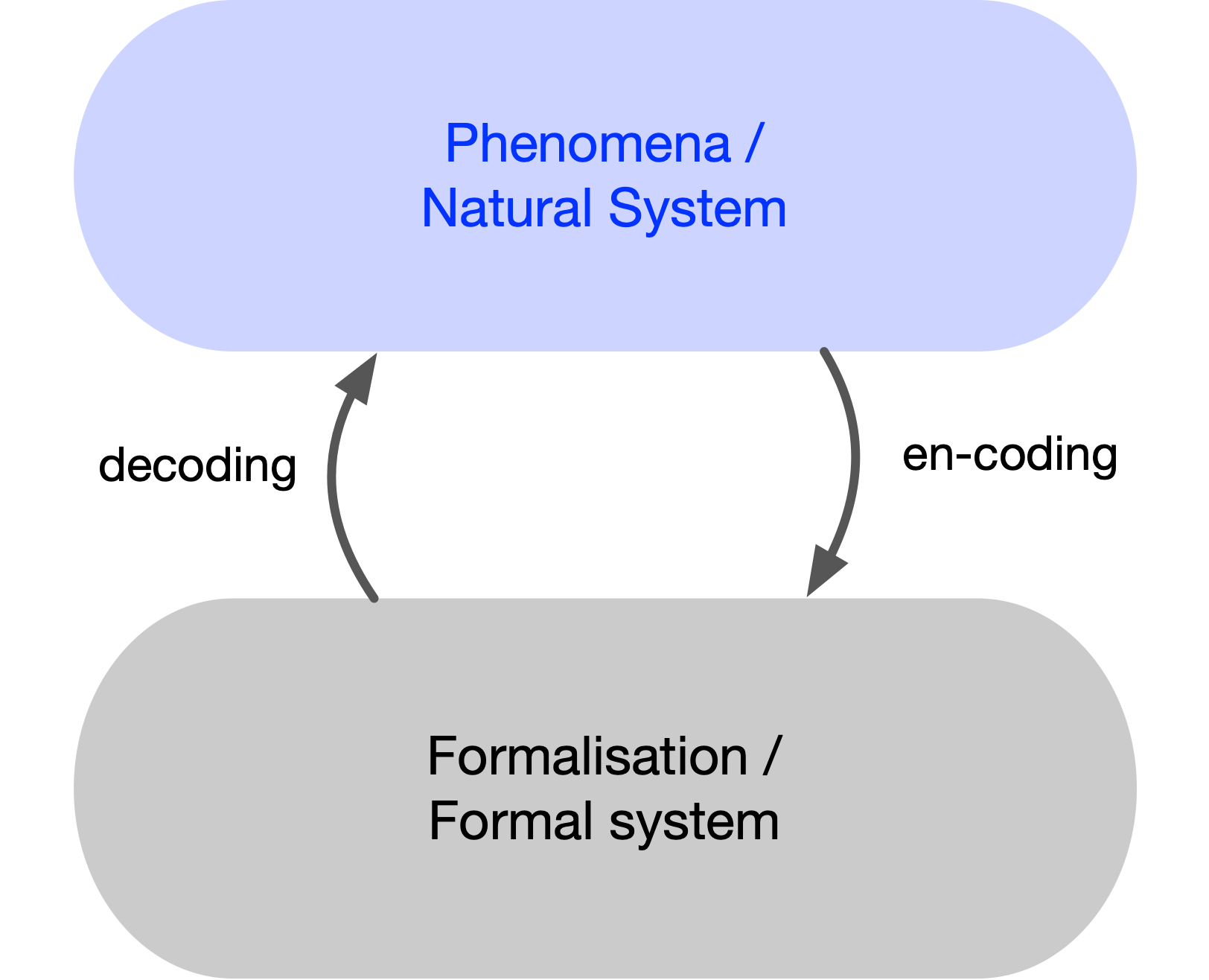

Science functions by providing a formal theory of phenomena: once phenomena are formalized, they can be accessed and manipulated directly. Robert Rosen, the theoretical biologist and founder of relational biology, introduced the idea of a modeling relation to study such formalizations of natural phenomena, including living organisms. The phenomena to be formalized constitute a natural system, while the resulting formalization is a formal system.

Rosen explored the relation between the two: a natural system can be encoded into a formal system, and the formal system can be decoded back into the natural one. Encoding corresponds to measurement: a meter acts as a transducer, associating elements of the formal domain (e.g., numbers on a thermometer) with phenomena (e.g., the thermometer–body interaction). Every measurement is an abstraction, replacing the thing measured with a limited set of formal elements. Decoding reverses this process, de-abstracting by mapping formal elements back to phenomena. When we read a number on a thermometer, we attribute it to a property of the body being measured—its temperature.

Entailments

State explosion and formal verification

To reproduce the results observed in the target domain, we must reconstruct or simulate those constraints within the implementation domain by whatever means are available to us there.

Constraints are essentially prime elements of a domain—they are irreducible to more primitive elements. In the target domain (of physical objects), a prime element is localization: an object occupying location A is a state that comes as an irreducible whole.

The implementation domain of computers does not have these primes; instead, it has very different ones of its own—the memory cell and the value stored in it.

Thus, we must use the primes of the implementation domain to model or simulate the primes of the target domain. What used to be an indivisible whole becomes a composite that can be broken down into parts.

This means that during encoding, we instantiate a one-to-many relation: we replace wholes with particles that must be glued together.

Note that the implementation domain can now have states that do not decode into anything in the target domain. These states are a side effect of the lack of constraints intrinsic to the target domain—the side effect of breaking prime elements of the target domain into particles that compose their emulation in the implementation domain. T

The implementation now has far more states than the target it is supposed to represent, and those additional states are meaningless in the target domain. The possibility of activating these states corresponds to the possibility of malfunction.

The fact that there are way more states in the implementation than in the target often appears under ‘state explosion‘ name and it arises out of incommensurability between implementation domain and target domain : it is due to our choice of implementation domain that we end up having to deal with the state explosion. The cause of the state explosion is the wrong choice of description or inappropriate formalisation of the target domain.

In formal software verification — particularly in model checking — there is a distinction between the formal model of a software system (e.g., a state machine or Kripke structure) and the formal properties that the model is expected to satisfy (typically specified in temporal logic). This method is commonly applied in practice to embedded software and hardware implementations — for example, ensuring that the software controlling an elevator never allows states in which the cabin moves with open doors.

However, when applied to higher-level software, model checking often encounters the state explosion problem, leading to significant effort being spent on reducing the state space that needs to be verified or checked. Even then, verifying real-world programming-language implementations against formal properties becomes intractable for most business domains that DCM targets.

With DCM, the implementation is specified at a much more domain-specific level of description, where there are orders of magnitude fewer degrees of freedom — and therefore fewer possible states. As a result, DCM avoids the state explosion problem inherent in programming languages (which merely render hardware states), since there is no incommensurability of scale between the target domain and the implementation domain.

Problems introduced by encoding

What must the implementation domain preserve in order to ensure that it is capable of serving as a model of the target domain? Roughly, we can think of the content of the target domain as consisting of things and relations between things — both being elements of the target domain. We can then look into encoding things and encoding relations.

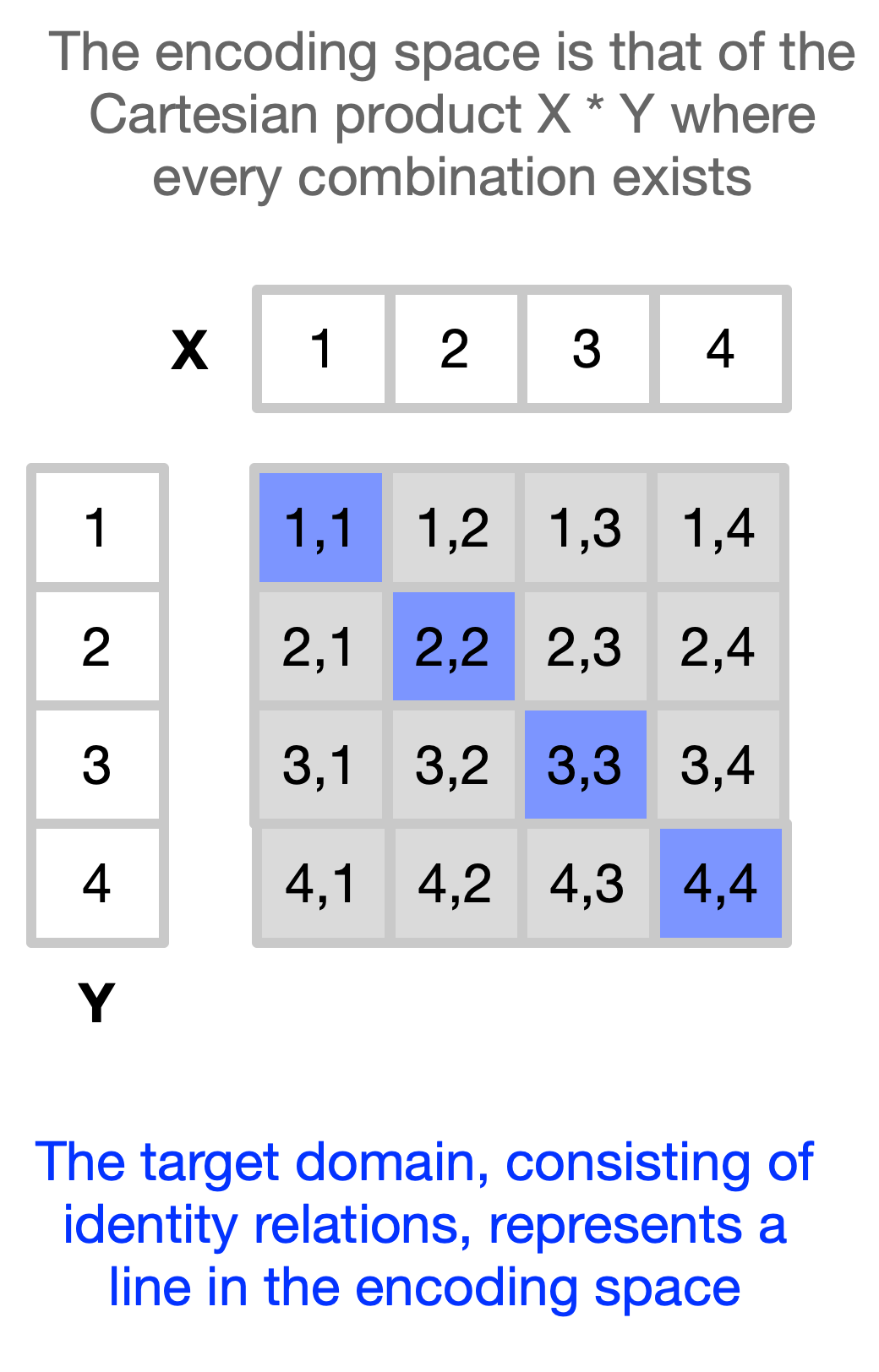

Ideally, the mapping between the two domains would be one-to-one: each element of the target domain would have a unique label in the implementation domain, and vice versa.

The main goal in encoding things is that the implementation domain should reproduce both the individuation (the delineation of distinct entities) and identification (the tracking of identity across appearances) structures of the target domain.

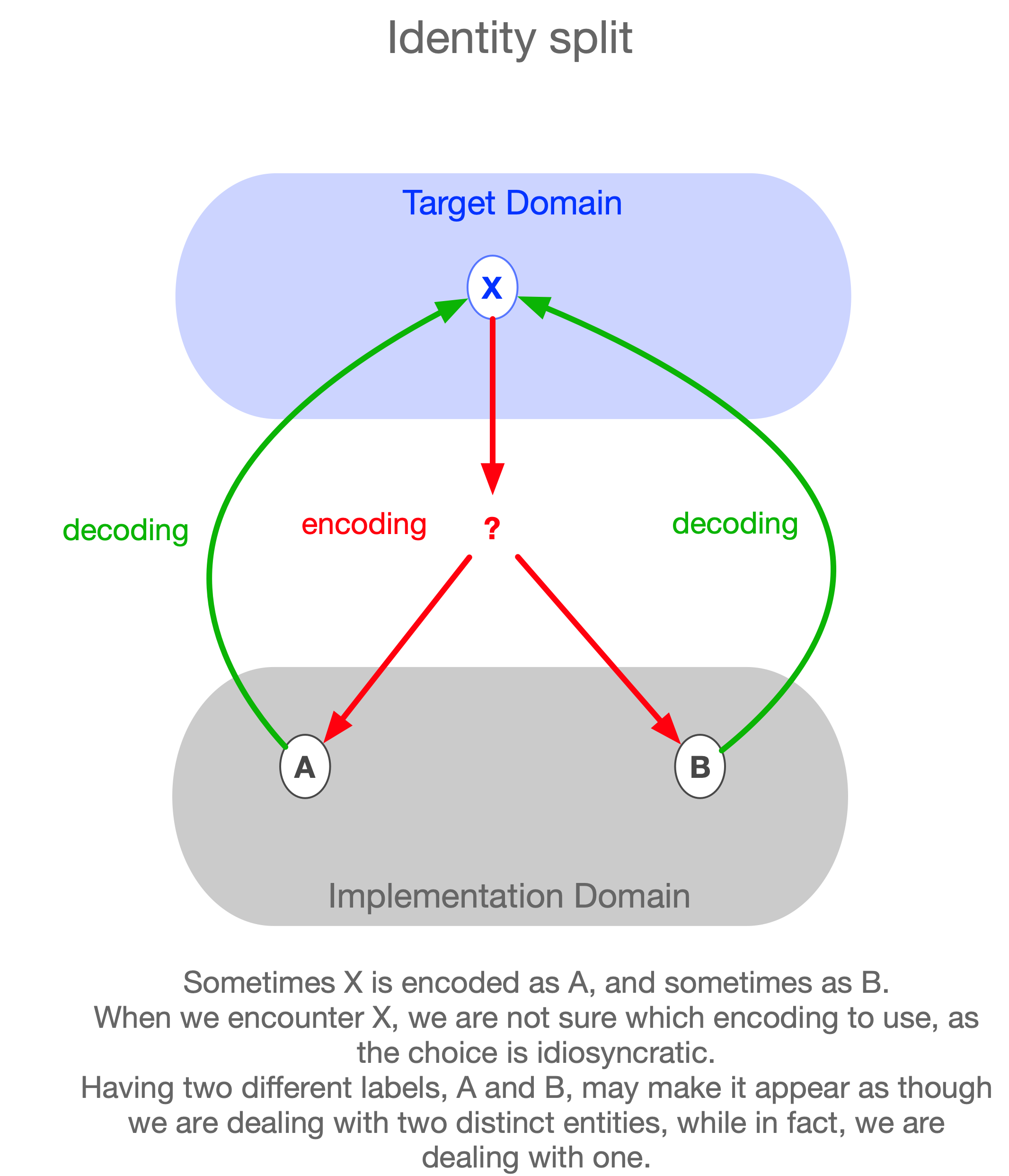

Split of Identity, multiple alternative encodings

The problem of the breakdown of identity appears in the philosophy of mind under the name “Paderewski case”. Paderewski cases are situations in which a subject associates two distinct identities with a single individual — the subject does not realize that it is the same person that he is dealing with.

This situation corresponds to a single target-domain object being represented by two distinct implementation-domain objects. On some occasions, the target object is encoded into one implementation object, and on other occasions into another. The person who is confused corresponds to someone whose knowledge is limited to the implementation domain. Such a person mistakenly believes that there are two distinct entities being dealt with, while in reality, there is only one.

Returning to the case of encoding into a PL: a single element of the target domain can have many alternative encodings. In other words, the implementation generates doppelgängers for elements of the target domain. For example, there may be multiple ways to encode a transaction within a given PL — such as using “+” and “–” signs to label buys and sells, or using a separate field called buy/sell indicator.

Such encoding errors can lead to two problematic situations: the implementation may lose inferential power (entailments that should concern the same object become split into unconnected fragments), or it may hold contradictory information about the target domain — for instance, stating mutually inconsistent facts about the same object, since from the implementation’s point of view, these appear as two different entities.

As we have seen with the space–time topology, this cannot be achieved when encoding domains based on physical space directly into PLs.

Individuation breaks down; the encoding becomes lossy.

But this phenomenon is not specific to software implementation or technical engineering. It arises from the very fact that there are two domains — two systems — where one represents the other.

If one domain is the physical world and the other the human brain, we encounter the very same problem again — only this time, it is a problem for the human brain to deal with, not for software.

Note that this problem cannot be solved simply by imposing a single encoding across the implementation. Because of the nature of the target domain, some of its content can only be represented indirectly, via projections. The same element of the target domain may have different construals (projections) under different circumstances, so multiple encodings may be an unavoidable requirement.

However, this does not remove the need to track their co-reference — to recognize within the software that several different elements are merely alternative encodings of the same identity in the target domain.

Only when identity is preserved can the implementation remain internally consistent.

Instead of multiple doppelgängers living independent lives, there will be multiple projections of a single original entity.

The very same trade can be viewed from the perspective of cash movement, price reporting, or security movements. Since each use case requires different information about the same trade, each will end up dealing with its own encoding. Thus, on one side we must preserve identities, while on the other, we must allow for alternative encodings of the same individual.

This is precisely what DCM achieves with its perspectival collage mode of composition — allowing for alternative construals that overlap on the same underlying content.

Bifurcating encodings introduce noise

The problem is that we cannot know which label is correct from the target domain’s point of view; what counts as right or wrong is arbitrary from the perspective of a business expert. This knowledge is essentially technical noise introduced into the system by the PL domain itself (which plays the role of the implementation domain).

In complex systems with many referents, guessing the right label can become akin to winning a lottery. This is where numerous heuristics enter the software development process: conventions, design patterns, best practices, templates, and even natural-language cues embedded in PL identifiers (variable names) all serve as tools for navigating this unfavorable situation. However, these are merely informal aids; they do not resolve the fundamental incommensurability between the PL domain and the target domain.

To work effectively with such a system, it is no longer sufficient to understand only the target domain (i.e., what the PL code is supposed to label). We must also know all the encoding choices made during implementation. This additional layer of idiosyncratic knowledge increases cognitive load, making the system more difficult to reason about. As a result, a domain expert approaching the system from the outside is often unable to comprehend the implementation — simply because they lack awareness of this idiosyncratic layer of encoding decisions that obscure the formal system description.

The number of elements in the PL domain is vastly greater than the number of elements in some specific target domain. This means that when we encode an application into PL code, we must select one representation from among many equally possible encodings.

At first glance, this abundance of options makes writing small pieces of code appear easy, since there are so many labels (alternative encodings) available in the implementation domain to choose from. We can simply pick any of them.

However, if we want to achieve internal consistency throughout the implementation, we must ensure that the same encoding is used consistently everywhere.

If, at different points, different encodings have been chosen for the same object (i.e., different labels attached to the same referent), we then need to recode one into another while preserving the reference to the target domain.

In other words, we must extend our formalization with an additional set of mappings between different encodings of the same element. Before using any object from the target domain, we therefore have to determine which label — among many possible ones — is the correct one.

From the perspective of domain intersection, this breakdown of individuation represents noise generated by the implementation — things you’ve got but didn’t want.

But his is only one side of the incommensurability problem between the two domains.

Its complement is the loss of information from the target domain within the implementation — things you wanted but didn’t get.

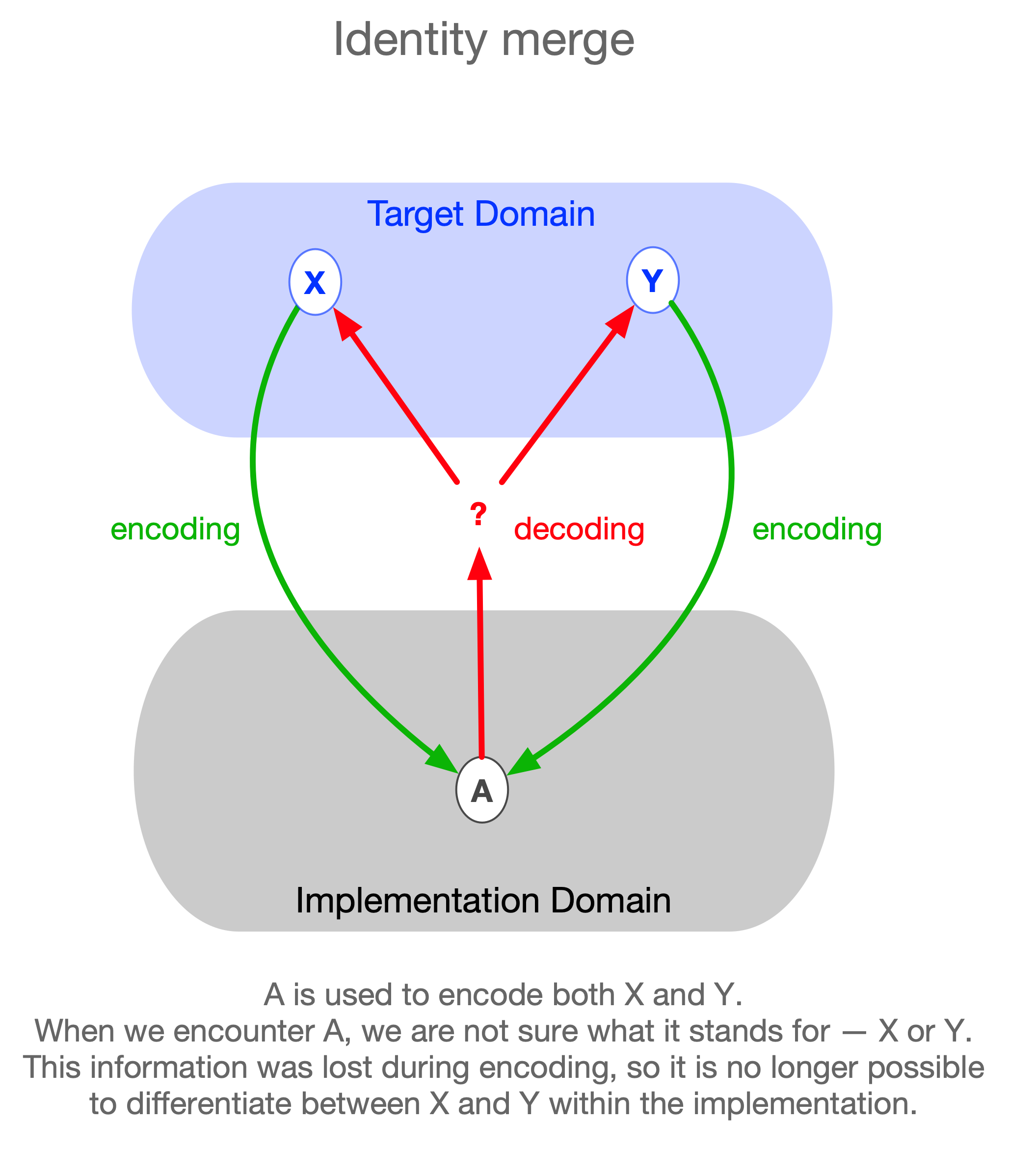

Merging Identities

This is an inverse Paderewski case. Inverse Paderewski cases are situations in which there are two distinct entities, but the subject associates them with a single identity — that is, the subject confuses or conflates the identities of two different individuals. Here, there are two different identities in the world, but the subject believes there is only one.

Consider the following example, due to Herman Cappelen (p.c.): There are two people, A and B, who share the same name (say, Cicero). John believes there is only one person by that name, so he freely mixes information he receives about A with information he receives about B, storing everything under a single entry. Having heard that A (Cicero) is bald and that B (also Cicero) is well-read, he concludes that a certain bald man is well-read.

This situation corresponds to two distinct target-domain objects both being encoded into the same implementation-domain object. Again, the confused subject corresponds to someone whose knowledge is limited to the implementation domain. Such a person mistakenly believes that only one object is being represented.

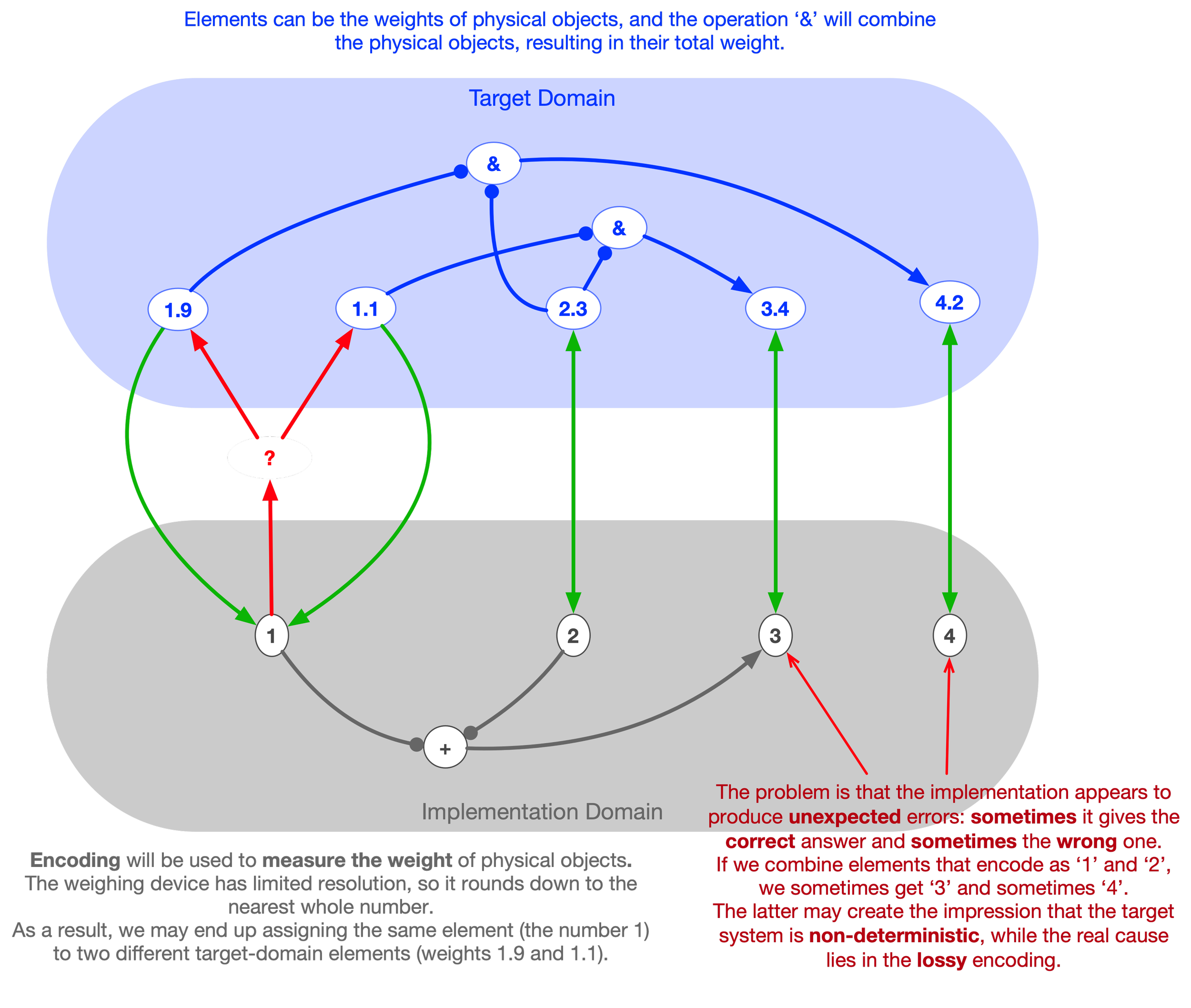

This encoding error can lead to situations in which inferences made within the implementation suddenly break down, creating the appearance that the target domain itself contains unpredictable errors or contradictions. In reality, these errors originate from lossy encoding, not from the target domain.

Everyone has direct experience of this phenomenon: when vision fails to deliver enough detail about moving objects at a distance — especially in conditions of low visibility, such as fog — we may see movement but cannot tell how many objects are moving, or what those objects are. As the fog lifts or the distance closes, perception gains resolution, allowing us to count and identify individual objects.

Analogously, in software design as target-domain encoding, we can encounter lossy encodings — encodings that collapse distinct entities into a single undifferentiated representation, or fail to encode certain entities altogether.

For instance, in financial trading, an exchange instrument may pass through multiple phases such as auction and continuous trading. If the software fails to encode these phases distinctly, it may treat them as identical, leading to erroneous behavior — for example, order rejections that appear causeless from within the system.

The issue worsens when we move to second-order strata — that is, when encoding relations between things. If the encoding cannot distinguish between different target-domain states, it cannot resolve the transitions between them. The inability to differentiate among target-domain entailments means that the implementation’s entailments (inferences) may deviate from the actual causal chains they are meant to represent, leading to erroneous behavior, loss of function, or malfunction.

Encoding Relations

An implementation must not only encode individual things but also the relations among them. A non-trivial target domain — such as that of settling a trade — involves entailments that represent the dynamics and causality within that domain. These second-order structures also require encoding.

While human beings can readily perceive physical objects, there is no corresponding mechanism for directly perceiving out-of-context relations. The fact that perceptual phenomena such as color are context-dependent — arising from relational structures rather than absolute physical quantities — and that humans can Gestalt spatial configurations into unified percepts or affordances, does not grant us the ability to perceive relations that have not been previously schematized.

This is related to the issue of objectification: for the mind, it is far easier to deal with first-order static entities — those corresponding to the construal of an object — than with relations, which require more complex cognitive constructions and less stable content, thereby demanding a higher cognitive load.

Yet it is often relations that possess greater causal power or ontological priority, meaning they are frequently more fundamental (and more useful) to a domain than the individual things that serve as their terms.

For example, a transaction is not an object, nor a mere collection of objects; it is constituted by relations or entailments between objects — such as the transfer of funds from a buyer to a seller.

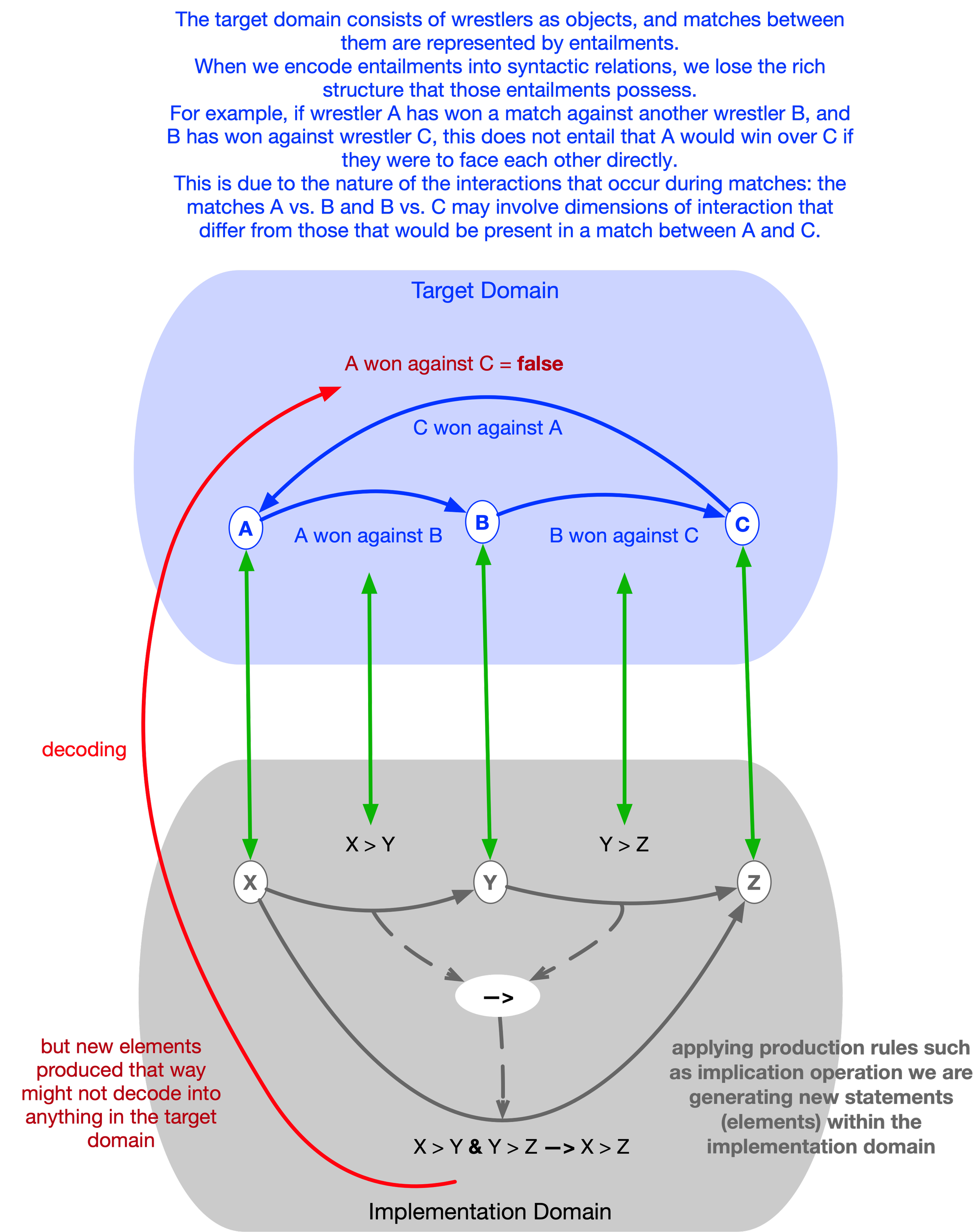

In programming languages (PLs), relations are typically expressed through syntactic composition — by combining symbols according to production rules. For instance, if A labels an account and C labels a client, the expression A @ Cmay label the relation “account of client.” Whether this proposition corresponds to something real in the target domain depends on external knowledge. Syntax can generate such composite labels indefinitely, but it cannot determine their truth or correspondence.

If the label A @ C decodes into an actual relation in the target domain, we call this a true proposition. Otherwise, if there is no element (relation) in the target domain that this proposition decodes into, we call it false. Note that the binary nature of propositions — being true or false — does not stem from their internal structure (which may have as many dimensions as we choose to give it) but from the binary correspondence between the implementation domain and the target domain.

The compositionality (or productivity) of syntax allows us to generate arbitrary labels simply by applying syntactic rules. However, as noted earlier, we have no way of determining whether any given proposition actually refers to something in the target domain without external knowledge of that domain. This is because the production rules of syntax — the inferential structure of the implementation domain — are decoupled from the entailments that exist in the target domain.

This means that even if we have an encoding that perfectly preserves first-order individuation and identification — a one-to-one mapping for things — we are not guaranteed that it will preserve the relations between those things. Such an encoding may contain relations among its own elements that do not exist in the target domain. In that case, the implementation can derail the train of computation from the tracks that exist in the target domain, arriving at results that are invalid within the target domain.

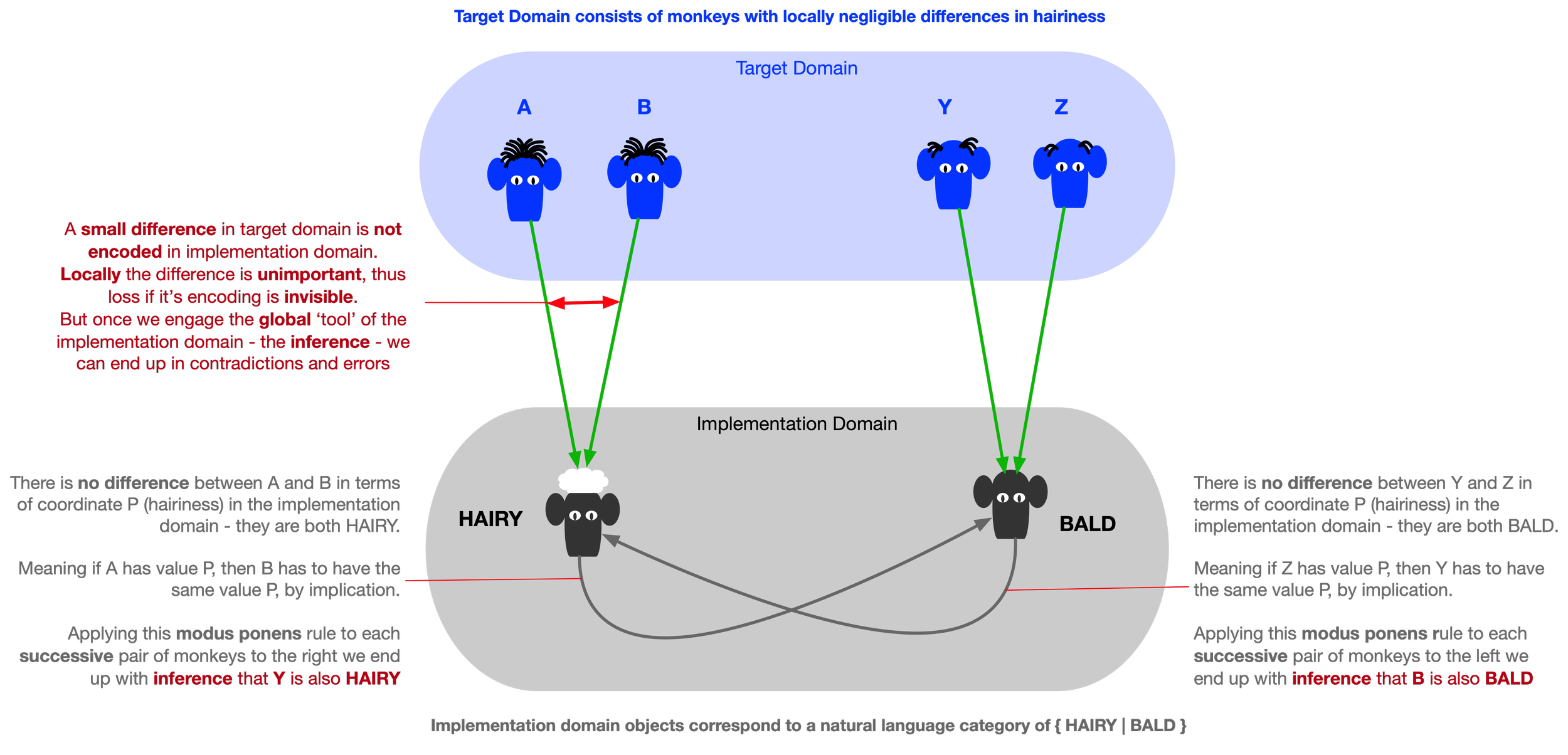

Balding Monkey Paradox

Suppose we have a group of monkeys lined up before us. The first one, A, has a lot of hair on its head. The last one, Z, is clearly bald. In between, there is a series of monkeys, each of whom has an imperceptibly lesser amount of cranial hair than their immediate neighbor.

It is also very plausible that if a given monkey in the lineup is hairy, then so is the next one to its immediate right, since there is no perceptible difference between the two. The same applies when starting from the bald monkey (on the right end) and moving to its neighbors on the left.

Being bald or hairy is a matter of appearance. So, if one monkey is bald and looks the same as the next monkey, then the next monkey must also be bald (as there is no difference between neighbours).

Z is bald. But given that there is no relevant difference between Z and its neighbor, monkey Y, the latter must also be bald. There is likewise no relevant difference between Y and its neighbor, so the third monkey from the right must also be bald. Continuing in this way, we arrive at the conclusion that A is bald — we end up with an element of the implementation domain that encodes a bald monkey. But A is hairy. Just check the encoding!

Thus, we arrive at a paradox — an apparent breakdown in reason — where we seem able to derive a contradiction by combining what appear to be impeccable premises with what appears to be impeccable reasoning. This problem is known as the Sorites Paradox.

This example shows how locally correct encodings can still produce errors in the implementation when combined with the global inferential power characteristic of syntactic implementation domains. A small encoding error that makes no difference to inference locally can accumulate along longer trajectories and eventually derail the inference from the original process it was meant to model.

How a lossy encoding can make a deterministic target look like a random one

Issues introduced when encoding things that may not be visible directly can lead to unpredictable issues in the encoding of relations, causing a fully deterministic target domain to appear non-deterministic within the implementation.

When viewed through the implementation, the target domain may seem to change or bifurcate spontaneously, whereas in reality, this is just a noise is introduced by the implementation itself due to information loss during encoding.

Syntax vs semantic

The way complex structures are composed in the PL domain (from things and relations between things as components) differs dramatically from the way complex structures arise in the target domain.

This productive capacity to create arbitrary structures in PLs stems from the recursivity of PL syntax and the absence of intrinsic semantics imposed by the compiler — beyond enforcing syntactic rules and hardware constraints (for example, the separation of data from the processes that generate and operate on it into two independent sets). However, the ability to create PL code that is syntactically correct does not imply that the resulting software has any meaning within a given target domain.

In other words, the combinatorial nature of the PL domain is unconnected to the target domain: the inferential structures of the PL domain do not necessarily have counterparts (entailments) in the target domain. The PL domain — including the compiler and related mechanisms — enforces form, not meaning.

Suppose we begin with a perfect one-to-one mapping between elements of the PL domain (such as key–value pairs) and those of the target domain — meaning that we preserve individuation for both things and relations.

Because of this one-to-one mapping, the elements of the implementation domain act as labels or names for corresponding elements that exist in the target domain. All of these labels are attached (that is, grounded in the target domain, having a meaning or interpretation).

As the previous section shows, by following all the composition rules of the PL, we can construct a larger structure (a larger program) from these lower-order elements — from those attached labels.

However, the new composite label (an element of the implementation domain) we have built from previously attached labels may turn out to be detached — semantically disconnected from anything in the target domain (having no meaning or contradicting the target domain - i.e. being false).

From the PL’s point of view, the resulting code is perfectly valid — it remains an element of the PL domain, obtained through a sequence of valid production rules, including operations such as implication. Yet, when we take the target domain into account, following this syntactically correct path does not guarantee that the resulting program (the source code) has any meaning or function — that is, that it decodes into something meaningful in the target domain.

Note that large language models (LLMs) exhibit a similar phenomenon, known as hallucination: the implementation domain consists of tokens, and producing an answer to a query triggers the generation of token sequences through pattern completion in an abstract space defined by the artificial neural network’s weights.

Yet, nothing guarantees that the tokens generated by such a process will correspond to correct referents in the target domain.

In the case of hallucination, the LLM produces grammatically and syntactically correct words that either lack any real meaning or are simply false — that is, they impose or attribute an element to the target domain that does not exist within it.

This phenomena is also related to Gödel’s incompleteness theorem, which demonstrates the incompleteness of any formal system with respect to its ability to infer all the facts about the world it generates — to know what is true or false, even about itself.

The difference between relations (combining several objects) that we can generate in the PL domain and those actually existing in a given target domain is analogous to the difference between the mathematical notions of a direct (Cartesian) product and a semi-direct product. The former has no constraints between its factors, allowing all possible combinations, whereas the latter, due to linkages between factors, represents a restricted subspace of the former’s product space.

This problem manifests under the name state explosion: the explosion occurs whenever a target domain is encoded into an incommensurable implementation domain, such that a single state of the target system encodes into a large number of states within the implementation system.

The explosion associated with encoding relations is typically of much greater magnitude than that arising when encoding things.

In this sense, the syntactic rules of PLs — being simple and devoid of information about any target domain — are like the direct product: they allow all combinations of labels, recursively labeling relations between labels without any constraint.

This lack of constraints enables us to map any target domain into a syntactic domain. However, this mapping is lossy: once we replace the target domain with its syntactic representation, we lose the very information that makes the target domain what it is.

The syntactic domain becomes the lowest common denominator among all possible domains — it erases the differences between them by discarding their unique internal structures.

Hence, within the PL’s syntactic domain alone, we cannot determine whether a given piece of code — a set of propositions or commands that modify memory cells — has any meaning for a specific target domain.

Perhaps not coincidentally, the process of writing PL code is called coding, not encoding.

Coding presupposes only a single domain — the syntactic domain of PL statements — whereas encoding assumes a relation between two domains.

The problem is that once we merely code a target domain into the (purely syntactic) PL domain, we lose the structure of the former, and there is no way to reconstruct it from within the latter.

The reason some code constitutes an implementation of something — rather than just an arbitrary collection of computer artifacts — lies outside that source code; it is absent from the implementation itself.

Breaking Modelling Relation : a cash movement

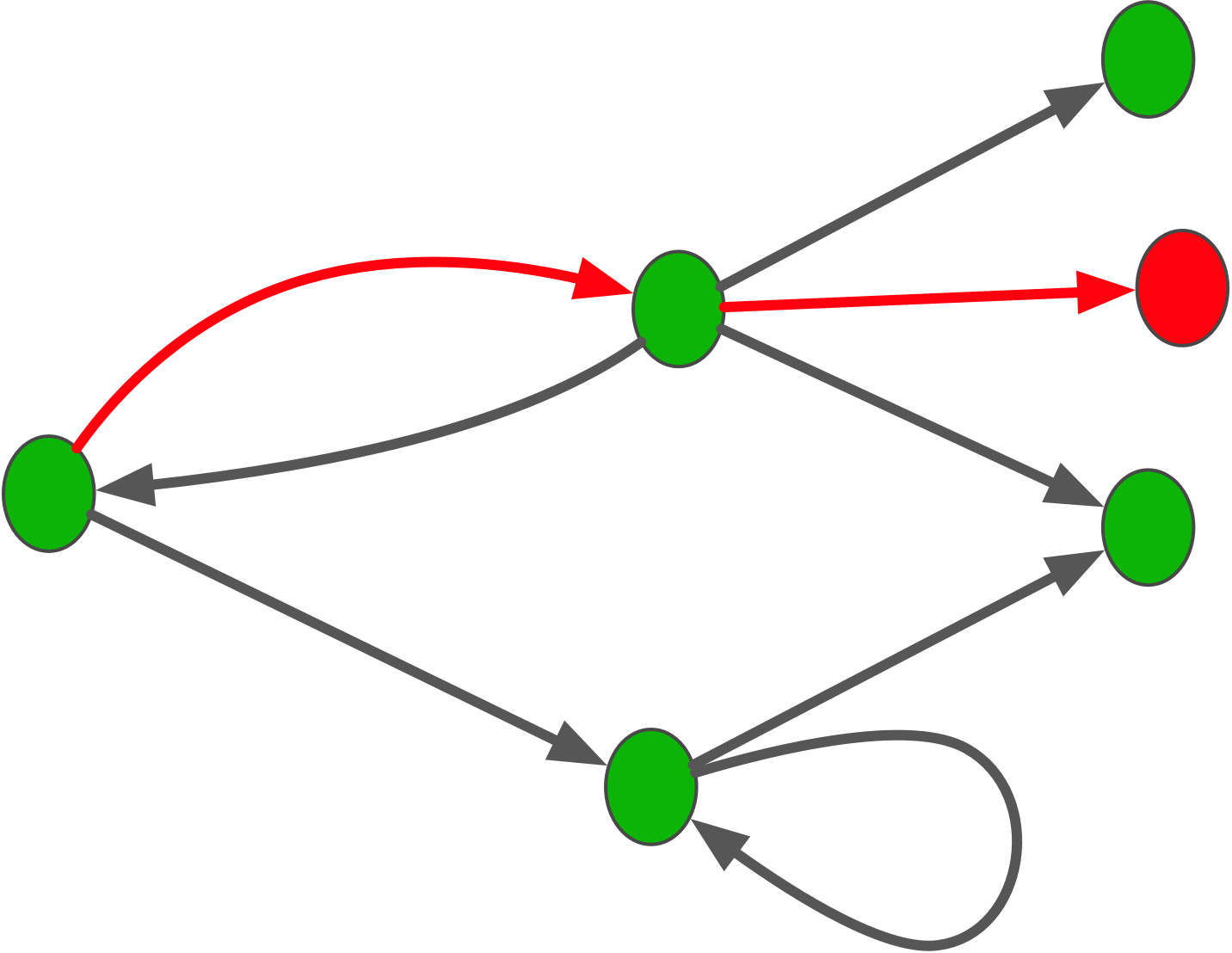

As the detailed diagram shows, a single state transition in the target may correspond to many transitions (a graph) in the implementation.

In the target domain, the movement of a physical object is a prime operation.

In the implementation domain, that operation is realized through memory cell read and write operations, together with arithmetic operations applied to the in-memory copy of a cell’s value.

This realisation is no longer a prime, but a composite.

The implementation system can now enter states that do not decode into anything in the target domain. Moreover, there can be periods of time during which this lack of correspondence between the two domains persists.

If we were to question an implementation with “What does this mean?” there would often be no synchronic answer: taking a memory dump does not necessarily reveal what the system was doing.

To interpret these undecodable states, we must instead adopt a diachronic perspective—examining state transitions rather than isolated states. This involves tracing the current state back to earlier, decodable states, and projecting it forward into later, decodable states that reveal what the system was intended to represent.

Clearly, such diachronic interpretation does not come “out of the box” in most programming language implementations. It typically requires significant manual effort to reconstruct.

This “red period” in the lifetime of an implementation system—when it passes through undecodable states—marks the temporal interval during which the modeling relation breaks down.

Note that the example presented here is intentionally simple.

When a single operation in the target domain is implemented as a set of microservices, the situation becomes even more problematic. Each service maintains its own representation of reality, decoupled from the others. As a result, the number of undecodable states (or states that decode incorrectly) within the implementation multiplies—along with the number of possible errors.

These problems are introduced during encoding, and the implementation must devise solutions to address them.

In our example of cash movement (or any financial instrument), such additional solutions include the introduction of mechanisms such as transactions and reconciliation.

These mechanisms provide a workaround for an artificially introduced problem. It is artificial because it does not exist in the target domain; it was created by the implementation domain during the encoding stage, owing to the absence of the appropriate primes or constraints that exist naturally in the target domain.

Conclusion

The result of these two problems arising during encoding is a breakdown of the modeling relation: the implementation begins to produce errors, malfunction, and can even lose its function.

Conventions, design patterns, and best practices serve only as local heuristics — ways to navigate out of a faulty position. They cannot resolve the structural incommensurability itself.

The approach DCM takes is to reformulate the problem. Instead of trying to bridge the incommensurability gap, DCM chooses a different implementation domain. Unlike the target domain, which is given to us at the outset, the implementation domain is a tool that we create in order to deal with the former.

Programming languages were not designed from the ground up to handle the kinds of target domains we are concerned with here. They were designed primarily to make number-crunching faster, being rooted in hardware architectures built for computation and storage rather than for reasoning about human interaction or cognition.

The latter serves as the starting point for DCM, which attempts to create an implementation domain aligned as closely as possible with the target domain. DCM thus sees the task of building software through the lens of the modeling relation: the implementation domain should be a direct formalization of the target domain, rather than a completely different domain that must then be bridged.

Since DCM must still run on computers, it is ultimately mapped into the PL domain. However, when building software that implements a specific target domain — such as contract management — the implementation is done in DCM terms, so that how DCM itself maps into the PL domain is not a concern at this stage. DCM, as an implementation domain, is already furnished with the right encodings, which can be applied directly rather than built from scratch. It is then the job of DCM to make these run on the PL as the underlying level.