Solving a problem involves Two Domains

When solving a problem, the problem itself originates from some domain, and this domain is something a solution should target, as a lens that has to focus on a distant object - will call it a target domain.

The important thing is that we do not have a direct access to the target without employing some kind of mediator that gives us access to it. When one wants to take a picture of an object, one has to use some form of photo camera that has a lens and a sensor.

Note : having no direct “access“ to target as noted here does not prevent “direct perception“ of the target, but that topic requires much more elaboration that is irrelevant here.

The solution to a problem originates from its own domain, distinct from the target - will call it an implementation domain.

When a lens is focusing on a distant object, the lens itself represents the implementation domain, and the distant object being photographed is the target domain.

The lens is the measuring instrument, while the system being measured is the distal object (with it’s environment).

With this metaphor is it easy to see a more fundamental interpretation of this :

Implementation Domain = measuring instrument and the act of measurement (the model)

Target Domain = the system being measured (the realisation)

Another metaphor is food in the fridge. One can have a nutrition plan in mind, expressed in terms of numbers of calories, carbs, fats, and proteins. That plan is the target domain. The content of the fridge is then the implementation domain.

Given the same implementation domain (food in the fridge), there can be different target domains. For example, if one is not interested in calculating calories but only concerned with removing certain allergens, that represents a different target domain. Or one might be concerned with taste, which is yet another target domain.

The same food in the fridge (the implementation domain) will have a good match (like the focus of the lens) with one target (protein intake) but a poor match with another (taste).

The same thing happens when we have a programming language as an implementation domain and "target" different business problems.

A good lens is one that allows you to see the distal target it is focused on, not the internal details of the lens itself or the image artefacts it introduces.

In this sense, the lens is transparent to its user and makes the distal target directly accessible to the user’s awareness.

Relation between Two Domains

This phenomena is fundamental in sciences and manifests itself under different names in different fields :

Occam’s Razor : minimising the noise (introduction of unnecessary entities)

Minimum Description Length (minimal model that fits the data)

Principle of Least Action (choosing a path requiring minimal energy expenditure)

Free Energy Principle (maximising prediction, minimising error of a model)

Maximisation of Recoverability (of the generative operations)

A particular version of it, central to DCM, is the Minimal Generating Kernel. It is minimal in terms of the size of its description—like a formula—meaning that if any part is removed, the desired outcome can no longer be produced (i.e., the full structure will no longer be generated). At the same time, it is generative, as each element in the description has rich inferential potential, allowing a large amount of content to be derived from a compact representation.

For example, in the section discussing the TRADE example, the TRADE frame serves as a Minimal Generating Kernel for the settlement process within a specific context (involving CUSTODY frames, etc.).

It is somewhat analogous to DNA generating an organism within an appropriate and specific environment.

Hacking: Hacking is essentially the exploitation of unintended collateral in the implementation

- the unwanted degrees of freedom (see the next section).

It usually remains out of sight—like the underwater part of an iceberg—because there is no single person who has a complete understanding of what exactly those areas in the diagram include.

As a result, gaps are left unaddressed, and no one is fully aware of what has been exposed. More on the nature and negative effects of this collateral will be discussed in the section "Why PL Is Not Enough."

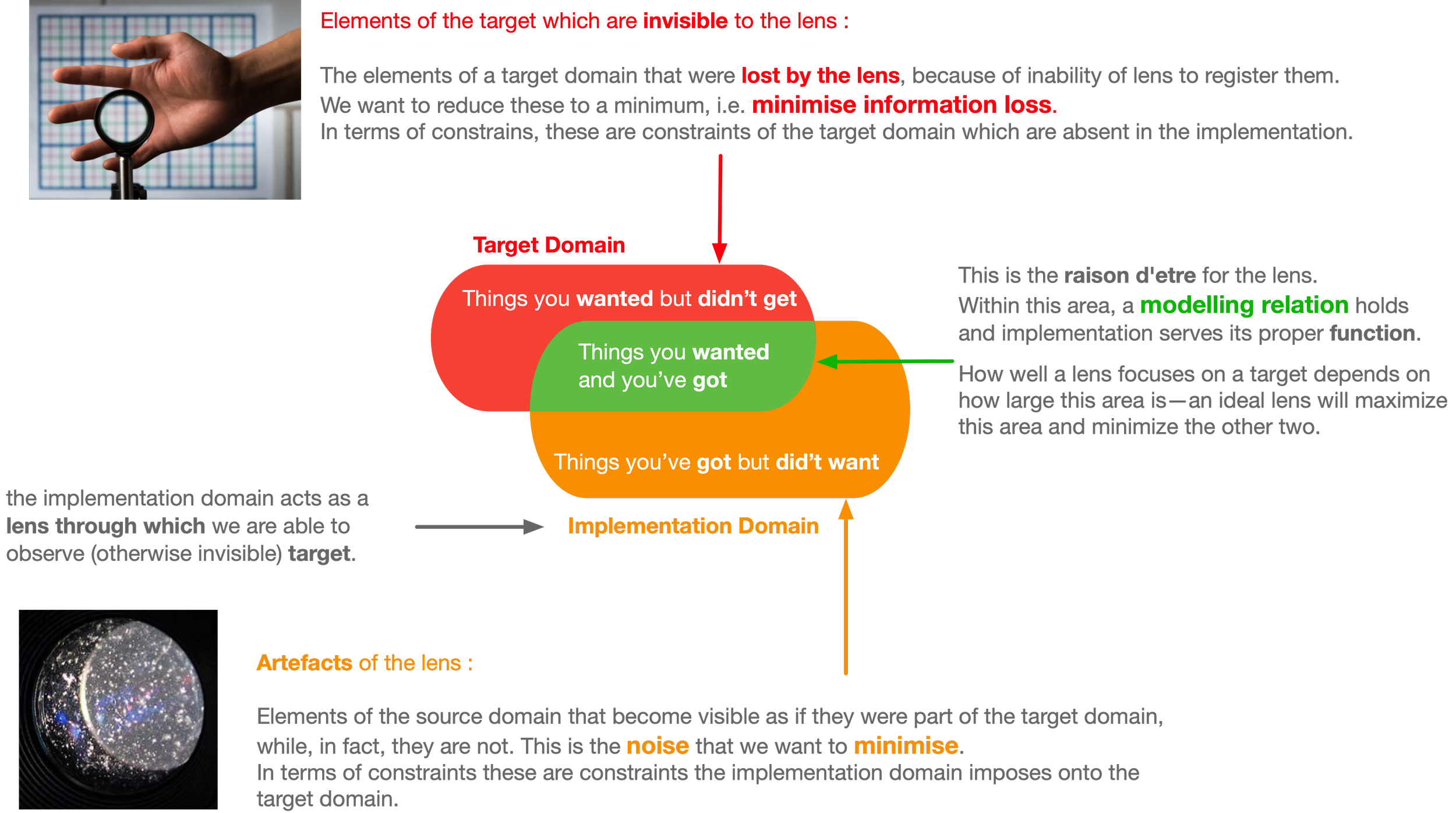

Using two overlapping squares as a metaphor highlights the relation between two domains.

In practice the implementation domain can never match perfectly the target domain, just as a measurement instrument can never perfectly convey all the information about the state of the system being measured.

For software systems, the implementation domain is usually a programming language code, while the target domain varies significantly - from streaming of movies to orchestrating complex financial contracts.

The further the target domain is from the way programming languages work, the less overlap there is between a software solution and the problem which it is supposed to solve.

The parts of the problem which get solved within a given implementation domain, usually come at a cost of introducing extra elements which have to be dealt with - these are artefacts of the implementation that have no counterparts in the target domain (elements which do not implement anything directly)

The more exact (formal) description of this is given in the section about Modelling Relation.

In language of category theory, the modelling relation is a Natural Transformation (the entailments of the target domain are preserved in the implementation domain and vice versa).

The Collateral Damage : things you’ve got but didn’t want

"Music is the space between the notes."

— Claude Debussy

The mismatch between the target domain and the implementation domain produces a part of the implementation that is not grounded in the target domain—the collateral damage: things you’ve got but didn’t want.

For a typical software system, the mismatch is large, and the size of the implementation is much greater than the size of the relevant area of the target domain. This results in a large set of unwanted degrees of freedom being shipped together with the solution (as an intrinsic part of such a solution). These are degrees of freedom that exist in the implementation but were absent in the target domain.

As argued elsewhere, the way these unwanted degrees of freedom arise—and their actual shape and size—is usually not tracked or accounted for, simply because they emerge automatically as a result of building software, while accounting for them requires additional effort and explicit manual intervention. Solving one problem creates two new technical problems, solving which may produce yet another set of technical problems, and so on.

This is a consequence of the lack of closure, which in turn results from the absence of a topological space in the implementation domain that could model the topological space of the target domain.

This is addressed in more detail in the section “Why PL is not enough“.

The very presence of these additional, unjustified degrees of freedom in the implementation is a negative affordance—meaning that the implementation makes certain undesired things possible. And the mere possibility carries the risk of actual exploitation of these unwanted degrees of freedom, resulting in side effects (defects, bugs, etc.).

The infamous NullPointerException is an everyday example in a typical Java application.

Thus, the ability to remove those unwanted degrees of freedom—or practically, to minimize them (minimise noise) —is the only secure solution to the presence of these defects and risks in building an implementation.

Minimizing them requires that the person doing the encoding knows the target domain very well—i.e., is a domain expert with respect to the relevant portion of the target domain being implemented (not necessarily the entire domain!).

In much of the traditional practice of building enterprise systems, coders often have only a vague idea of what the target domain even is—let alone attempting to formalize it. As a result, they naturally produce a lot of collateral damage, often without being consciously aware of it. That is, they do not even acknowledge that some of what they produce consists of these unwanted degrees of freedom (to say nothing of preserving the ones already present in the target domain - “things you wanted but didn’t get”).

The presence of too many degrees of freedom in the PL code allows developers to compensate for their lack of knowledge of the target domain, because it permits many different ways to simulate a given element of the domain.

This many-to-one relation, while making coding easier (it requires much less mental effort to find one solution when there are many suitable ones, compared to a situation where there is only one correct answer), comes at the cost of contaminating the implementation with these unwanted degrees of freedom—planting negative affordances into the system.

These affordances tend to accumulate and amplify over time (like any error in a complex system does), especially as the size of the system grows, as is argued elsewhere on this site.

Hence, solutioning ahead of understanding the problem becomes a ratcheting mechanism that plants the seed of collateral damage into the implementation—a seed that, over time, will grow in unpredictable ways, making the system harder to change, harder to understand, and more prone to bugs and uncalculated operational risks.

This collateral is basically a Chekhov’s Gun (attributed to Anton Chekhov) :

"If in the first act you have hung a pistol on the wall, then in the following one it should be fired. Otherwise, don't put it there."