Representing Space : Topology, Mereology

As the analysis below will suggest, programming languages (Java, C, Go, Rust) are closer to dressed-up machine instructions than true languages.

They were shaped by grouping machine-level instructions into convenient packages, embellished with language-like syntax and human-readable labels. The source code of PLs is usually called high level relative to the output of compilers, which produce machine instructions (whether real or virtual simulations). But the semantics of PLs largely remain those of the underlying hardware.

In programming languages (PLs), variables (or values) are fully independent storage cells with addresses (sometimes assigned human-readable nicknames). There are no inherent constraints on the values of these cells. If cell A holds a specific value (e.g., the number 123), this in no way constrains the values of other cells, nor is the value of A dependent on any other cells. At this core level, there is a complete absence of linkages or constraints.

If we consider the state of such a program, its state space is the direct product of all its memory cells, treated as independent coordinates. This space is enormous in scale, even for very small programs.

This was the central problem faced by formal software verification methods such as model checking, and it is known as the state explosion problem. What was called “explosion” is precisely this direct product of all independent coordinates. One of the main ideas behind DCM is to highlight that this problem is artificially created by applying an inappropriate encoding.

The lack of constraints (allowing all degrees of freedom between coordinates) makes it possible to program virtually anything. But being a “jack of all trades” also means being inefficient at each.

Implementing target domains such as financial operations or contract management directly in PL code is like drawing shapes such as spheres or cylinders pixel by pixel, without using geometry.

This analogy, though simple, is revealing in terms of the practical consequences of such an approach. A dedicated section, “The Absence of a Generating Kernel,” explores this further.

In short, individual memory cells and the instructions that read/write them are like individual pixels. There is no geometry at play that can generate an entire shape from minimal initial information (a generating kernel), such as the center and radius of a circle.

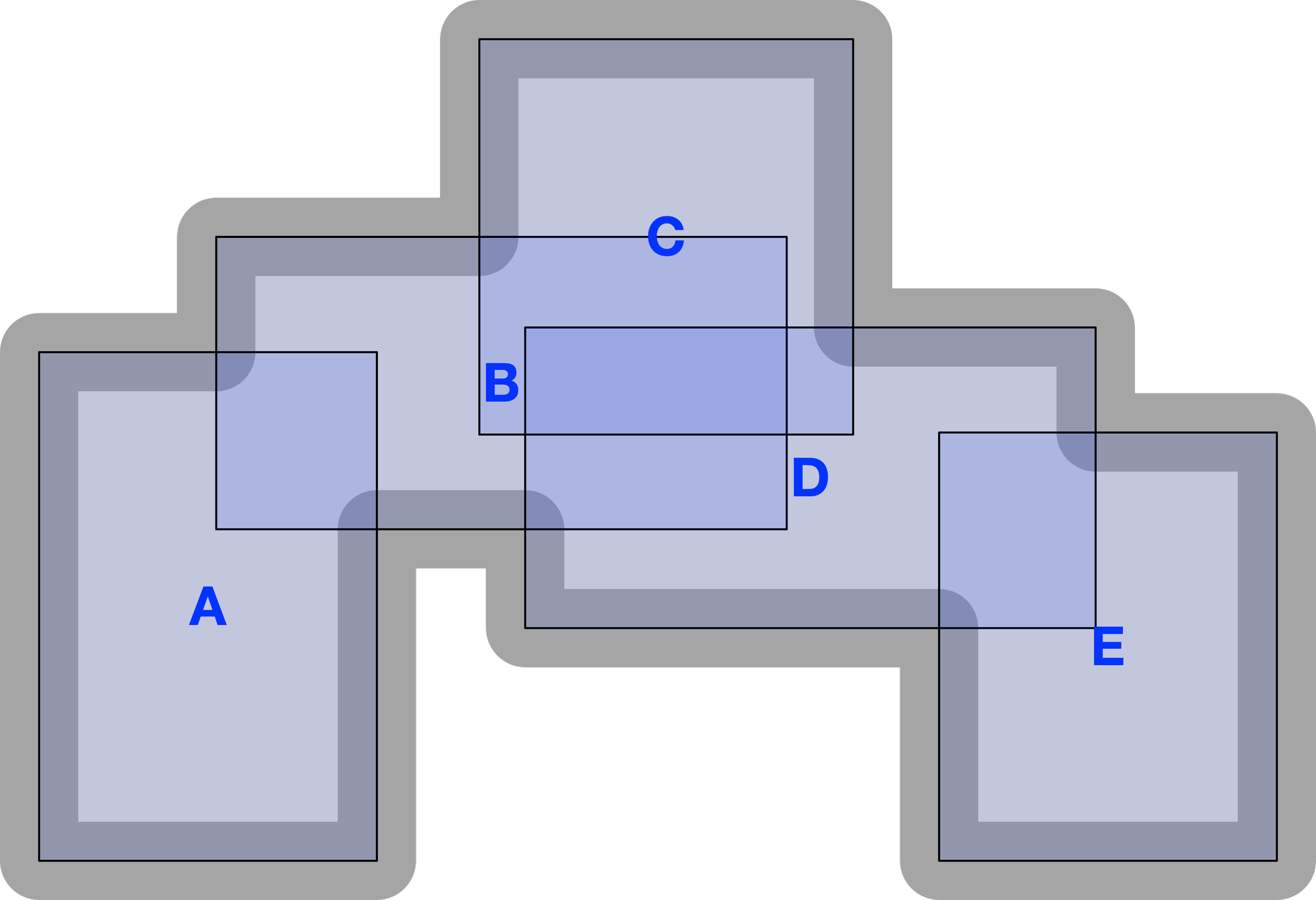

Comparing general Programming Languages and DCM

Ignoring metaphysics does not make one free of metaphysical commitments; it only makes one unaware of the kind of metaphysics one is building upon. The construction of systems—especially software systems intended for non-trivial domains—cannot remain innocent or ignorant of this issue.

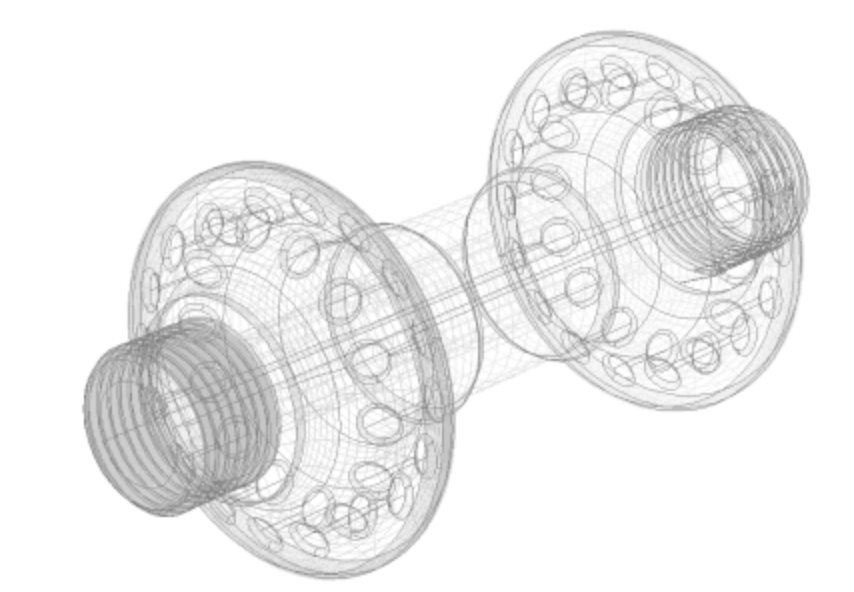

In contrast, DCM comes with an explicit a space-time structure (Topological and Mereological), meaning that only certain arrangements of elements are permitted—and these arrangements constrain where additional elements can be placed.

More formally, DCM introduces linkages (dependencies) between coordinates. In abstract mathematical terms, the DCM space is a semi-direct product of its coordinates. This makes it much smaller than the space generated by a direct product, which applies to independent memory cells in traditional systems.

There is no concept of an independent memory cell acting as passive storage that can simply be written to or read from, as is the case with variables in traditional programming languages (PLs). DCM does not have the notion of a “variable.” Instead, it has the notion of a coordinate, and different coordinates can be inherently linked.

DCM attempts to capture the same constraints between coordinates that are present in real-world human experience. These constraints constitute the topology and mereology of the DCM coordinate space, reflecting that of a physical space-time, thought rendered indirectly, through the cognitive domain. Capturing this structure is like capturing the laws of geometry: knowing the value of some coordinates, we can apply these linkages (laws) to infer the values of others, without needing to explicitly specify them all.

To describe something in DCM, we only need to specify the generating kernel—the bare minimum of information—and let the rest of the DCM inferential logic fill in the gaps, just as geometry infers all the points of a circle given its center and radius. The key to generating the right shape is for DCM to stand in a modeling relation to the target domain—meaning that the constraints of DCM must be isomorphic (map one-to-one) to the constraints of the target domain.

DCM is not unique in adopting this “generating kernel” approach based on preserving a modeling relation. A similar approach has long been used in fields such as computer graphics, design, and manufacturing. The adoption of such tools has led to significant success in their respective domains. Examples include CAD (computer-aided design) tools like SolidWorks for product design and manufacturing, and Autodesk 3ds Max for architectural design.

All these tools employ a geometrical core—a formal theory of objects in space. DCM follows the same principle, except that the space it models is not three-dimensional physical space but a conceptual space. Interestingly, CAD tools and DCM even employ the same mathematical constructs automating copy-pasting of structures (see the section on the mathematical interpretation of DCM).

Another useful metaphor is that of a 3D printer: DCM is like a printer that “prints” with PL-level constructs (directly executable on computers), while holding a 3D model of the target object “in mind.” The user specifies a model for contracts, and the system then fleshes them out—or “IT-prints” them.

Replication and loss of identity

The most common operation in programming languages is the creation of new content—independent groups of memory cells (sets of key–value pairs)—most often by copying or replicating existing content. For example, assigning a value from one memory cell to another, so that one variable takes the value of another. Such operations are typically packaged into larger composite constructs, such as instantiating a class or creating a message to be passed between components.

This is an inevitable consequence of computer hardware topology leaking into programming languages: having, as the prime element, an independent memory cell that can be read and written to (whether the cell resides in memory, cache, or a CPU register). Having this set of primitive operations requires allocating new memory cells to perform computation.

This reliance on replication is a direct consequence of computer hardware topology leaking into programming languages :

having, as the prime element, an independent memory cell that can be read and written to (whether the cell resides in memory, cache, or a CPU register). Having this set of primitive operations requires allocating new memory cells to perform computation.

Memory cells, however, are inherently unconnected. It is therefore the programmer’s responsibility to impose whatever constraints are necessary by writing code that enforces them.

By contrast, target domains such as contract management are the opposite: they are rich in inherent constraints from the outset.

A further complication arises from the prevailing methodology of software development, which proceeds by implementing small features (or “stories”) in short iterations (sprints). Within this environment, when tasked with implementing a single element of the target domain, the path of least resistance is to rely on dispositional semantics (discussed later) rather than putting in the effort to reconstruct the constraints of the target domain first and then relying on those to do most of the work.

The latter approach is broader in scope, cannot typically be accomplished within a few weeks, and does not have an immediate business impact.

If the building process continues over a longer period, this short-sighted strategy of repeatedly taking shortcuts stops being effective.

Encoding debt accumulates, and the time and effort required to modify the system grows disproportionately.

Eventually, the cumulative cost of implementing features piecemeal surpasses the one-time cost of encoding the topology of the target domain and expressing new features directly at the semantic level. The latter approach, though demanding greater initial investment, yields increasing returns—much like learning arithmetic eliminates the need to memorize a result of every possible calculation.

Two factors therefore combine to inflate complexity: the absence of domain constraints in programming languages, and the short-sighted strategy of treating the system as an aggregate of independent features, piled together like bricks in a wall. Both are reductionist: they reduce the whole to a sum of disconnected parts.

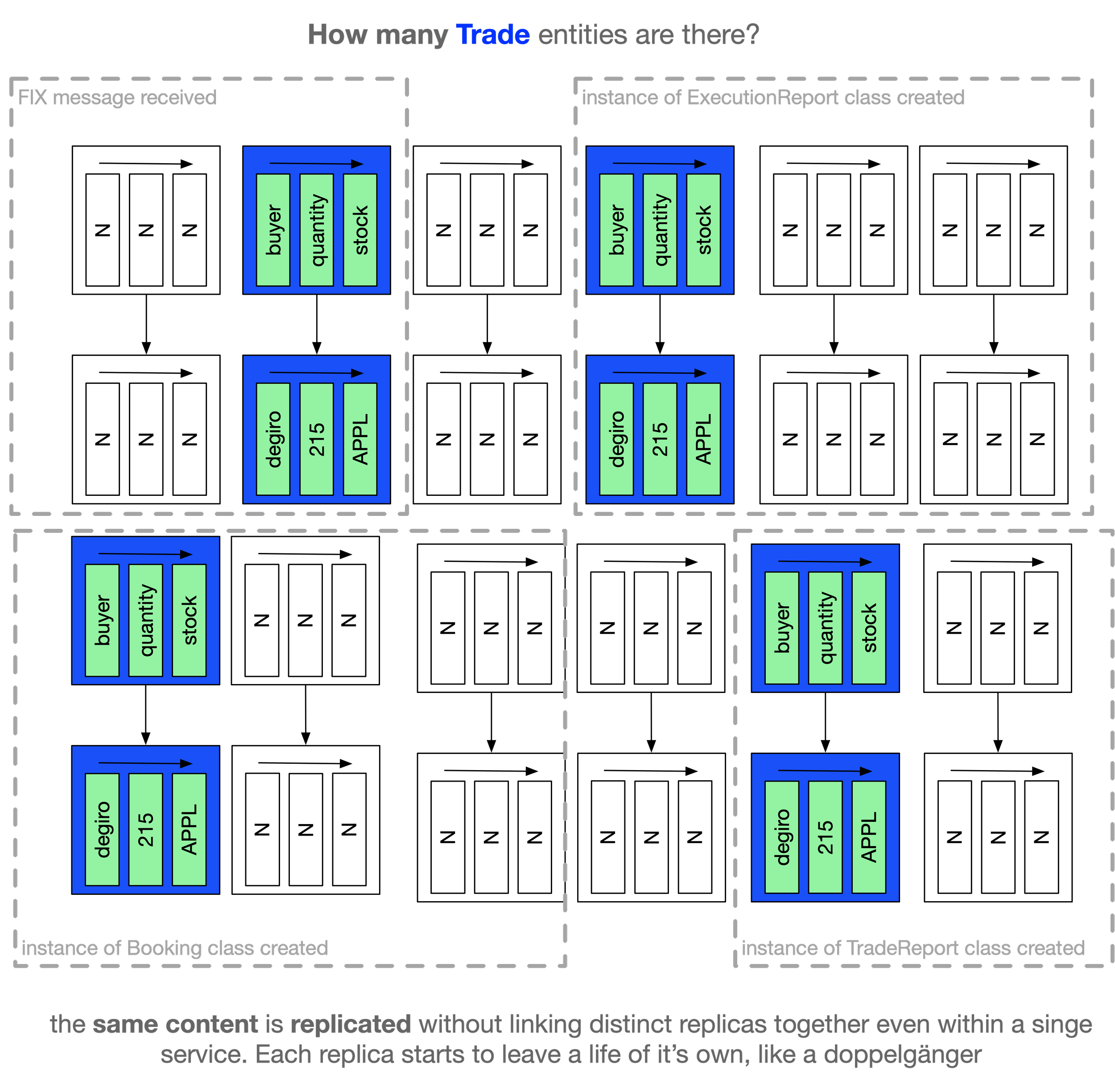

The consequence is that a single target-domain object typically generates numerous independent replicas—one for each feature, and one for each encoding. In a trade-processing system, for instance, the same trade is often represented as multiple key–value pair structures, each encoded differently.

These replicas are distributed across the memory spaces of various services, as well as across the underlying databases that support them. The consequence is that a single target-domain object typically generates many independent snapshots or replicas or doppelgängers (one per feature, one per encoding).

A typical trade processing system will often have numerous copies of a key-value pair representation of a trade, each with idiosyncratic differences in encoding.

These replicas are scattered across the memory spaces of various applications (services) involved in processing the trade. Still more replicas exist across the underlying storage systems supporting the databases used by those applications.

There is no built-in mechanism to link all of these particles as replicas of a single target-domain object (e.g., a trade). They are all decoupled. This is yet another instance of the Humpty-Dumpty problem discussed earlier.

This proliferation of replicas also violates Occam’s razor: what was originally a single identity in the target domain becomes fragmented into many identities in the implementation domain.

Individuation at the programming language level is thus inflated relative to individuation in the target domain. Put differently, the implementation domain, as a medium, does not preserve the individuation present in the target domain.

One consequence of this is the need to manually introduce technical unique identifiers (UUIDs, primary keys, etc.) to reconstruct and track the identity of a target-domain object that was lost in translation and fragmented into many unconnected doppelgängers.

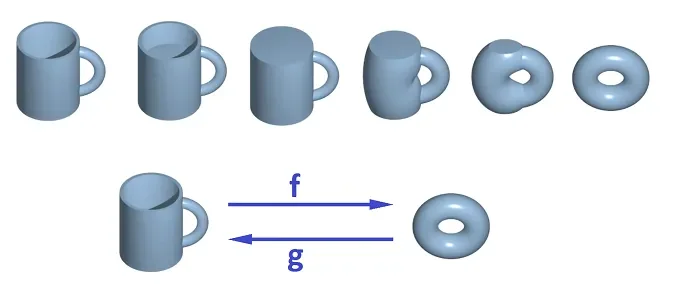

In DCM the most common operation is changing POV on the same content. The content is not replicated, the observerof the content is just adopting a different point of view from which the very same content gives a different projection ( a different construal of the same content within the observer ).

The identity of an object in the target domain is thus never lost, because it is not being downgraded into a set of independent snapshots.

Informally this means that DCM follows Occam’s razor in not introducing any new entities which were not present at the outset in the target domain.

Another, more formal way to express this is: the individuation in DCM is isomorphic to the individuation in the target domain.

Hence there is no need to introduce “technical unique identifiers“, the word technical already indicates that is something unnatural or foreign to the problem domain, it is a “crutch” that needs to be added to an already limping solution.

Thus DCM as a a medium maximises transfer (preservation) of individuation inherent in the target domain.

That does not only apply to individuation of objects that are things (represented by classes in Java) but also to individuation of all prime elements of the target domain - including individuation of events.

Note that identification is secondary to individuation—what cannot be delineated cannot be tracked. If individuation is preserved, there is no need to introduce new forms of identification that were absent in the target domain.

Perspectivity of DCM preserves identity

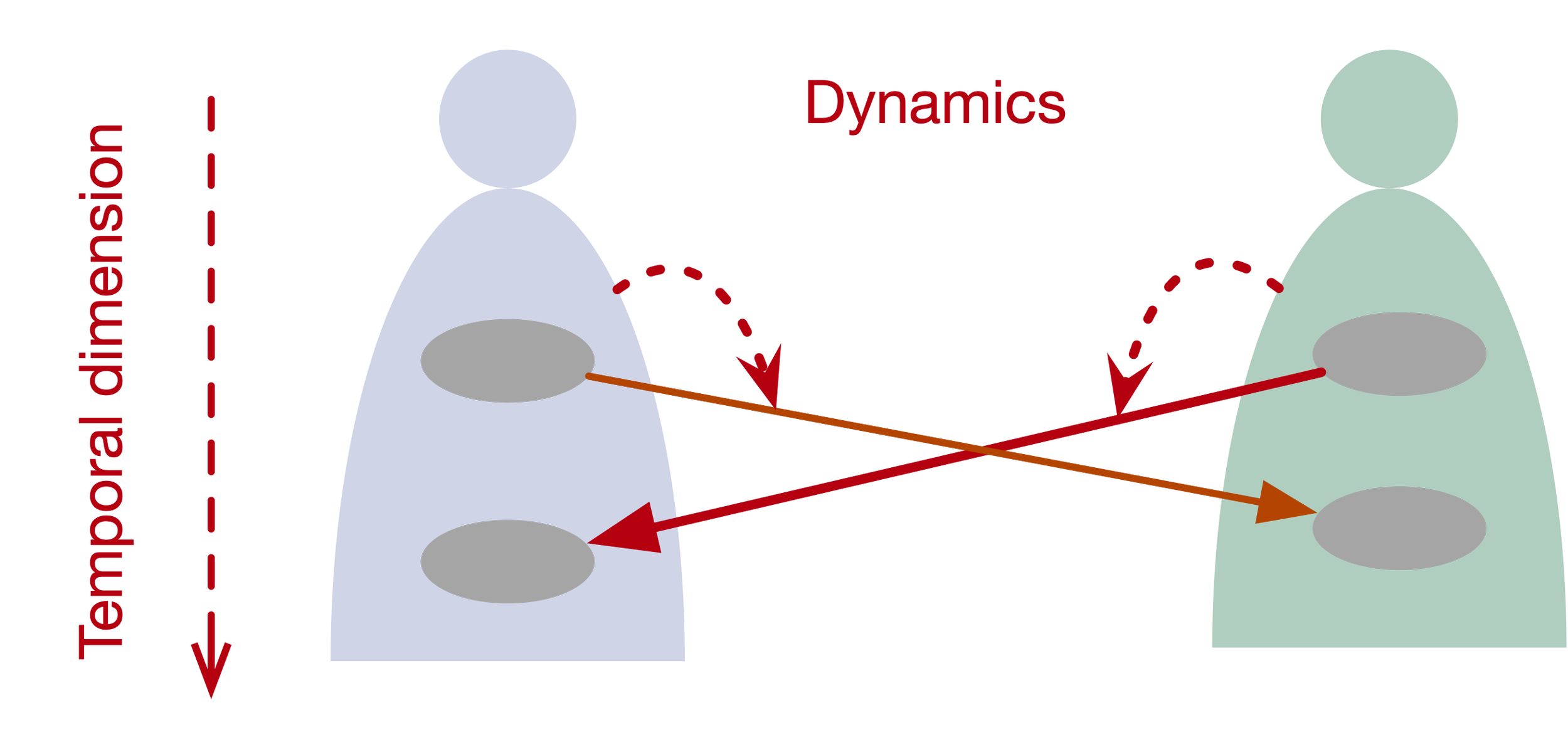

Dynamics and Temporality

The breaking down of target-domain entities into independent replicas within the implementation domain, though relatively easy to visualize for things, is even more pronounced for other categories of elements—especially processes and events.

When speaking of things, one can at least resort to groups of memory cells as representations. But for processes or events, programming languages (PLs) offer no adequate category.

This is again a consequence of the way PL were built - bottom-up being shaped by hardware architectures (especially Von Neumann), having no influence from target domains such as the ones considered here (contract management, etc). The code was supposed to encode number crunching and not human-like reasoning.

An interface, subroutine definition, or method signature is still a thing—a product of reification. It consists of two sets of things: inputs and outputs. It has no temporal dimension or dynamics.

A subroutine (function, method) is not a process. It is merely a sequential set of independent instructions, executed by the CPU in the order they appear—an order that bears no intrinsic relation to the order present in the target domain.

Some of the order present in a subroutine may originate in the target domain, while some arises purely from the implementation domain. From the perspective of a compiler, however, there is no way to distinguish between the two.

A sequence of instructions is just that: an ordered set. It does not contain enough structure to constitute a process.

If a PL were truly a language (rather than a dressed-up set of computer instructions), it would have a prime category for representing processes—just as natural language does with verbs (verb phrases).

Furthermore, there would need to be some categorization or schematization mechanism for processes, not just for things. While PLs provide limited mechanisms for categorizing things (e.g., through class inheritance), nothing comparable exists for processes. This is expected, since categorization requires first being able to represent the essence of what is being categorized—and a process is neither a simple input–output pair nor a sequence of commands reading/writing memory cells or changing control flow.

A direct consequence of lacking a notion of a process or dynamics is that the temporal dimension is also missing: there is no representation of time as an objectified domain into which all source code is embedded—while still allowing the system to adopt a reflective stance on that temporal context. Time only appears at execution—runtime or real-time—not as a first-class element in the model.

This is another point where PL is falling short in capacity when compared to natural languages which represent a human experience where a temporal dimension is an intrinsic part of.

In DCM, the most fundamental building block is a frame, which directly construes a process (e.g., RELEASE, MOV, EXCHANGE). Thus, unlike in PLs, the most basic building block of DCM is a process rather than a thing.

A frame with degenerate dynamics (such as CUSTODY) construes stasis—the persistence of a configuration or relation. It still carries a minimal temporal dimension, allowing figure–ground discrimination, and corresponds to a snapshot of a process that lies outside the scope of the frame.

To borrow the language of software development: processes and events are first-class citizens in DCM.

A process involves employing a form of morphology to represent and classify change as it unfolds over time against a fixed background. This categorization allows an open class of actual processes to acquire computer-interpretable semantics by being assigned to one of the elements in the closed class. The latter is essentially a sub-class of the one found in natural language.

Since frames are constructed from other frames in a collage-like manner—by superimposing frames on top of one another—the same mechanism that enables the gradual construction of things also enables the gradual construction of processes.

For example, an EXCHANGE frame, understood as a process (or event), embeds two instances of a MOVE process (or event). In turn, each MOVE process embeds both a RELEASE and a CAPTURE. The temporal dimension and dynamics go hand in hand; these two are tightly linked.

Dynamics in DCM

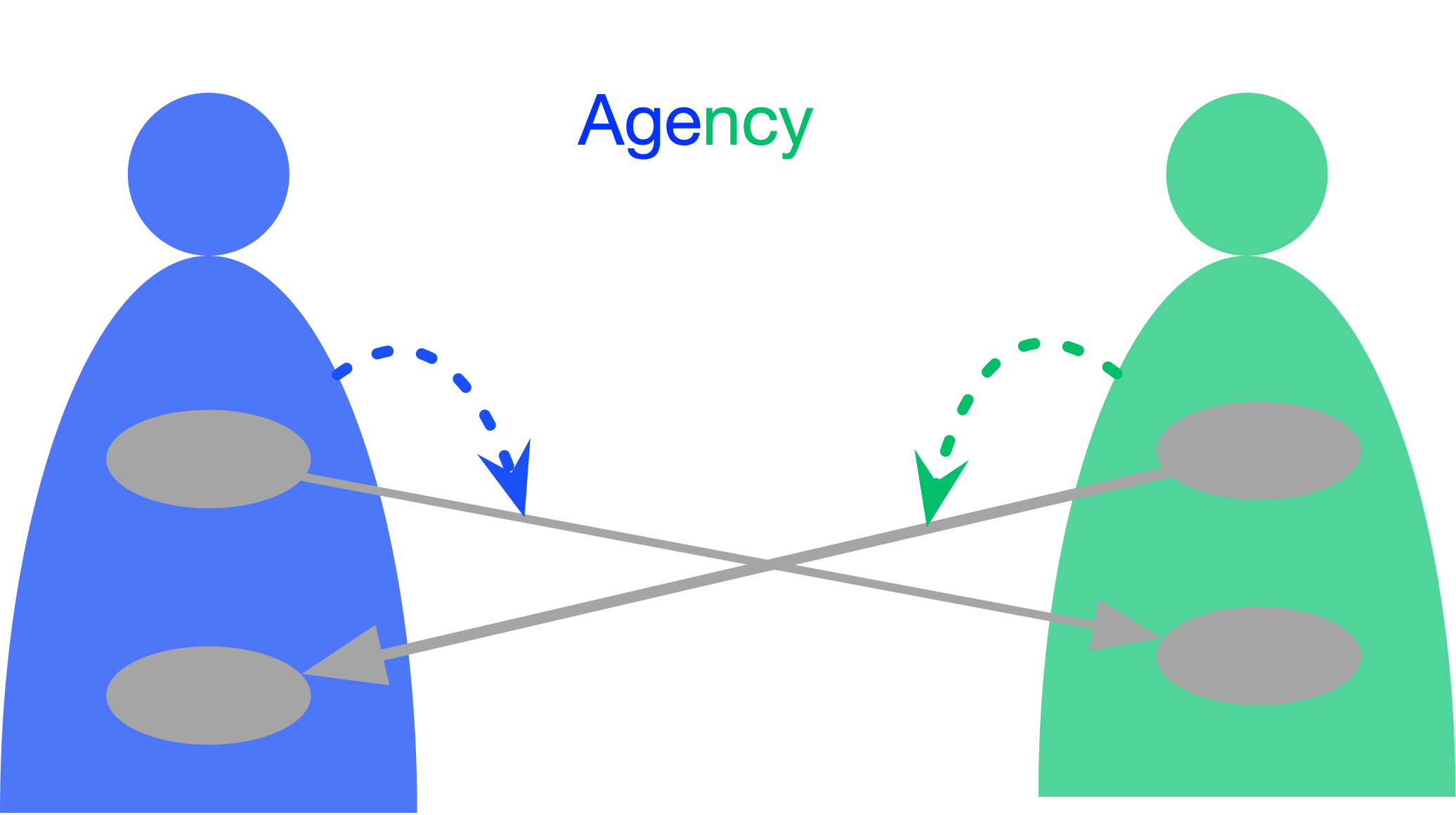

Agency in DCM

Agency

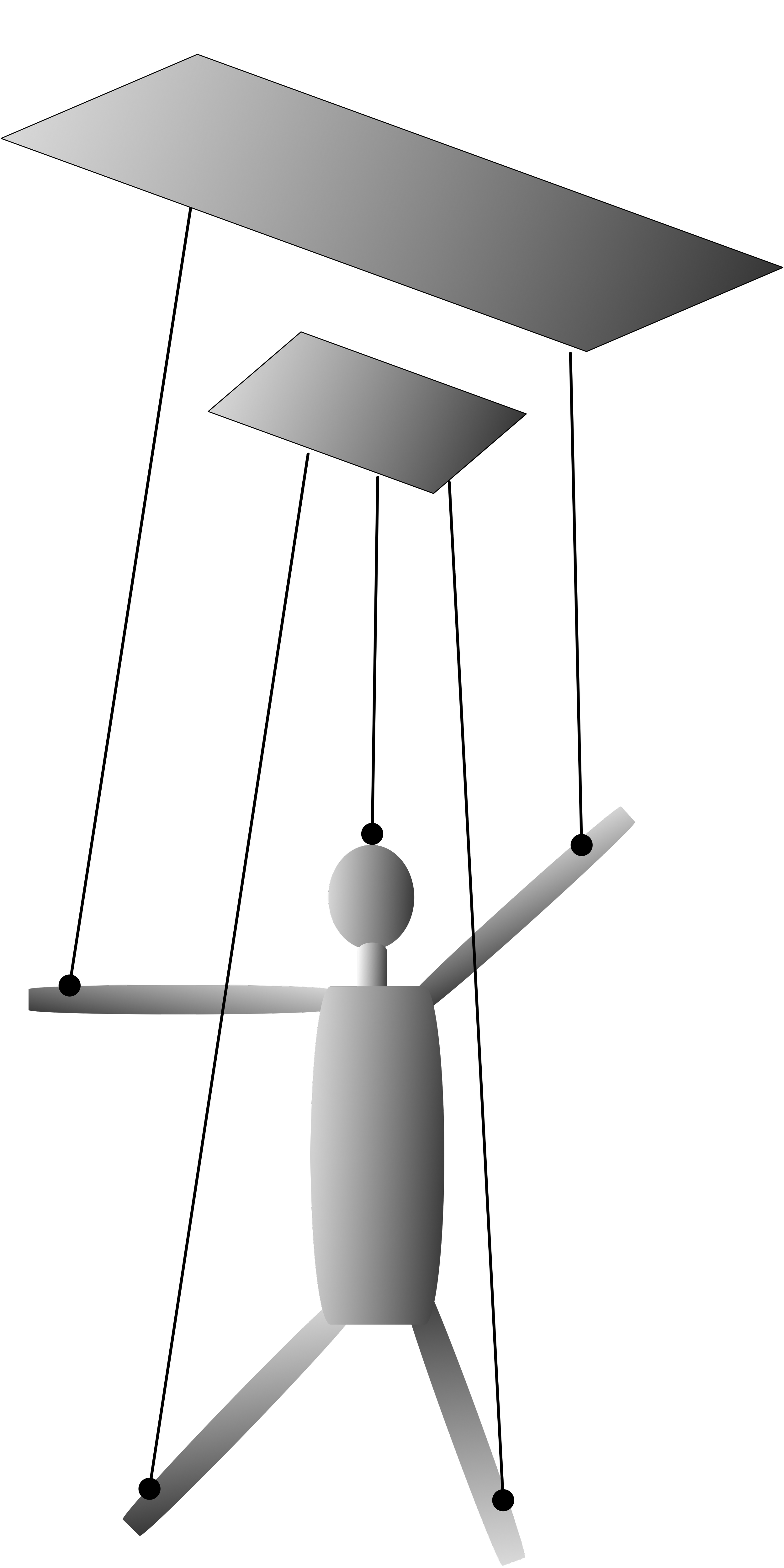

As mentioned in the previous section, the repertoire of constructs comprising a programming language (PL) is borrowed from computer hardware rather than from human (or any other organism’s) language. Unlike natural language, which distinguishes between objects and subjects, PLs make no such distinction. They do not acknowledge that two fundamentally different kinds of entities are involved: passive things and active agents.

All data is treated as a collection of passive values, typically arranged into key–value pairs, while operations on this data are carried out by CPU threads or similar mechanisms. There is no correspondence between the notion of a PL thread and the concept of a subject or agent in cognition (human or any other animal). This mirrors the absence of correspondence between a process (expressed as a verb in natural language) and a subroutine (a sequence of instructions), as discussed in the previous section.

Like a subroutine, a thread is a purely technical construct rooted in the hardware domain: a division between a potentially unlimited but passive set of storage cells and a comparatively small yet active processing unit (CPU/GPU), which is the only source of change within a computer system. The only “activity” in a computer is the processing unit manipulating data in memory cells (register)—or sending and receiving values over a medium to or from another computer.

Because of this absence of a notion of agency—which is intrinsic to many target domains (e.g., contract management)—any manipulation of data or transfer of data across a network is anonymous. There is no clear answer to the question “Who did that?”

The framing of such a question assumes discriminating notions of subject and object. But in computer languages there is no subject: an object ‘calling a method’ on another object is merely a marketing slogan for branching control flow, anthropomorphizing the latter.

Everything remains framed in a passive stance.

Data is simply being modified; datagrams are simply being copied over the network. At the technical level, the “doer” is just the machinery itself. In Aristotelian terms, this corresponds only to an efficient cause. Saying “This was done by Thread 123” or “Socket 345” is meaningless in response to a domain-level question such as “Who moved the stock into the securities account?”

This situation is analogous to observer-less physics, cognizer-less linguistics, and similar frameworks that abstract away the role of agency.

Just as the absence of a concept of process leaves something fundamental missing, so too does the absence of a concept of agency. If such a foundational element is absent at the level of base assumptions (where the axioms omit a key dimension), then anything built on top of that foundation risks eventual collapse—a failure rooted in that missing element.

Even if we treat a “thread” as simulating an agent—anthropomorphizing a technical construct—there is still no built-in concept of a dynamic process unfolding through causality. A thread merely executes a set of instructions in some sequence (or in parallel), typically altering the values of memory cells. At best, there may be data-flow dependencies, but even these often fail to map onto real dependencies in the target domain—and vice versa.

A direct consequence of this lack of agency and dynamics is the absence of a coherent notion of causality.

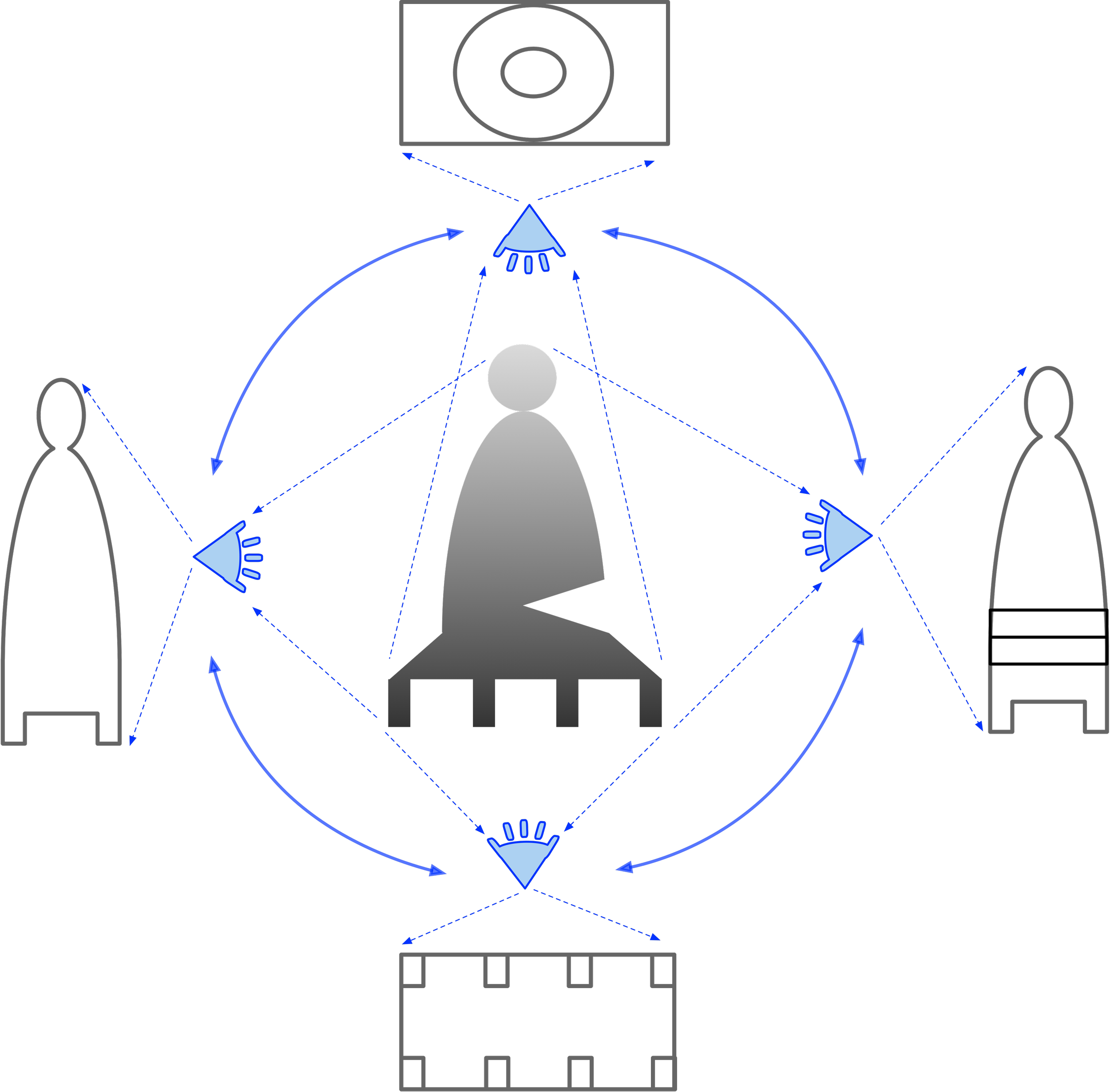

The notion of agency is a foundational element within DCM. It corresponds to the semantic role of a subject in linguistics and to agency in cognitive science. There is no action without an agent.

Furthermore, due to the multi-pane nature of content construal in DCM, an action can be located in both the content pane and the information pane. That is, there is no knowledge without an agent—no disembodied set of data floating in a vacuum, and no anonymous hand reaching into this vacuum to change the dataset.

This enables DCM to answer the question “Who?” at the level of the target domain. For example, if the question is posed about a stock movement from a nostro account at a custodian, the answer could be: “The buyer's custodian.”

This brings us to a fundamental principle: building the larger from the smaller, but in a way where the “smaller” parts are not intrinsic, independent components of a whole. Instead, they are projections or measurements made by an observer of the same target, observed through several interlinked "meters."

Forces enacted by agents are necessarily embedded in time, which serves as a clear example of such linkage.

Agents are not only embedded within the temporal dimension—they can also adopt a reflective stance toward it. For example, a bank agent given an instruction to credit a client’s account can "look at the clock" to determine the time the instruction was received, then refer to a contract that defines a constraint (e.g., the credit must be completed by the end of day X). The agent can then compute the time remaining and schedule the credit in a way that minimizes overhead and expense, while still fulfilling the terms of the contract it has entered into with another agent (the client).

Because of recognition of agency as a prime building block, a natural consequence is the need to implement a theory of action and interaction (between several agents).

The very notion of action requires the idea of a dynamic unfolding—through forces acting on objects, where the sources of those forces are agents. Actions can range from a limited set of primes to complex events composed of many interactions, each of which is composed out of those prime elements.

Another implication is that the action model must incorporate both a model of causality and a temporal dimension at the foundational level.

Thus, DCM, as an "abstract space," includes the core dimensions of agency, actions and forces, causality, and temporality.

These are not afterthoughts or features added on top which are decomposable into other dimensions, being thus merely simulated.

Moreover, these are not truly "orthogonal dimensions," as they are not independent. There are precise linkages among them. It is therefore more accurate to say that agency, change, forces, causality, and time are all projections—that is, measurements made by a human observer—of an underlying phenomenon (the system being observed).

The model of a complex event, such as trade processing, has to deconstruct its target along those dimensions in a way that preserves their interrelations; otherwise, it would not be a model, strictly speaking.

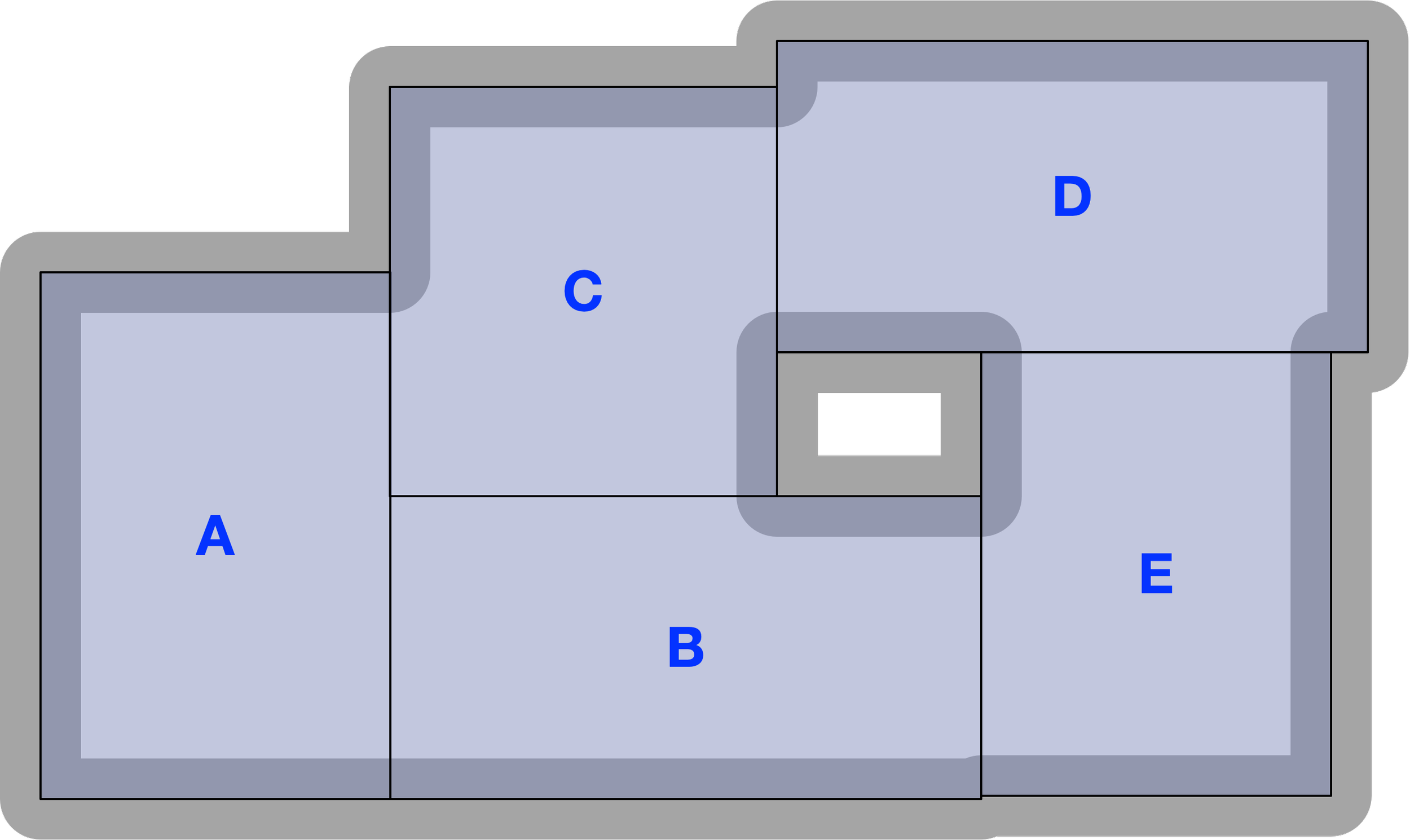

Ways of building large from small : lego blocks vs collage

Software is traditionally built according to a brick wall or Lego-block metaphor. The building blocks are treated as intrinsic and proper parts of the whole—without which the whole does not exist. Just like a wall is built by placing bricks next to each other, the resulting larger structure is composed of non-overlapping components.

This mode of construction, though simple in itself, imposes a single, exclusive compositional hierarchy and does not allow for alternative decompositions.

There must be only one way to decompose, and therefore only one single viewpoint on a given content—one that is granted a privileged status.

Often, significant effort is spent in software design attempting to establish a canonical decomposition. However, this decomposition is typically not formally grounded, but rather a matter of convention, thereby introducing yet another source of encoding idiosyncrasy into the implementation.

With this way of composition, the number of components in a composite grows linearly with the size of the structure being built: the larger the structure, the more components must be present simultaneously to cover it.

In DCM, building follows a collage metaphor. Smaller elements are projected onto a larger construction, with some parts sticking out and others overlapping.

Because DCM recognizes two domains from the start, it treats the target domain as content that cannot be directly accessed or seen all at once. Instead, only the relevant fragments of the target domain need to be construed "on the spot" in order to afford a specific action. This is achieved by the frame construct in DCM.

As discussed earlier, DCM supports multiple points of view (POVs) on the same content, which are complementary rather than mutually exclusive. Any target-domain element can be rendered in the implementation domain through its projections, each corresponding to a distinct POV. The implementation emerges by superimposing these POVs on the same target.

Where POVs overlap, their shared content provides a bridge that links them; through this mediation, even their non-overlapping areas can be related.

This mode of composition is rooted in a specific version of mereotopology inherent in human conceptualization (cognition), rather than merely mirroring how ordinary physical objects are embedded in space (the naïve Lego-block mode of composition).

Human Scaling

If the implementation domain is too low-level relative to the target domain, a single element of the target must be encoded into many elements of the implementation. The implementation then inflates in scale, with no systematic way to compress it to the limits of human cognition.

It is important to stress that these cognitive limits are not defects but features. They enable a range of operations—such as those constrained by working memory—that would become impossible if the limits were relaxed. This is one of the fundamental constants of human cognition, yet it is too often ignored in engineering practice.

As development progresses, implementations eventually accumulate more components than can be comprehended at once. They lose the human scale. Developers can still work with such systems, but only by resorting to strategies of search, trial, and reconstruction that impose far greater effort than should be necessary.

Once a target domain is encoded into implementation domain, transparency of the encoding tends to degrade over time. This is due both to the nature of human memory—which does not store knowledge as static objects in containers—and to the semantics of programming languages themselves. Over time, the system becomes a black box.

Extending or adjusting such a system requires reconstituting its meaning in the developer’s mind.

This re-comprehension demands bringing into awareness all parts of the implementation, regardless of what is actually relevant to the problem at hand (a change or a new feature to be implemented).

There is no efficient, systematic way to make a change only along the relevant degrees of freedom. There is no way to “see through” the codebase without first effortfully ignoring irrelevant components and actively searching for the right extension points along which the change can be made.

A more efficient design would expose the content of the implementation directly, avoiding the need to traverse deep compositional hierarchies or decode irrelevant elements.

As the system grows, the ratio of effort overhead to the size of an actual change increases sharply. This “gravitational inertia” of the implementation—its resistance to change—expands disproportionately with scale.

If the system being built is complex by nature, choosing a tool that is too simple may result in shifting the complexity elsewhere. Even if each step in the construction is easy, the final product may be very difficult to change or repair. This is a form of accumulated debt - the encoding debt.

Each POV highlights certain aspects while concealing others, so the broader domain is gradually revealed through a sequence of limited “windows.”

This approach enables scaling: keeping each POV relatively small while allowing the overall content to expand. In this way, DCM preserves a human scale in the implementation domain, ensuring that all relevant implementation elements remain cognitively accessible. However, this method of construction also means that larger structures are not fully compositional in the traditional sense; there may be no single, unique way to decompose something into parts.

Traditional software development offers no real counterpart. Programming languages support only fully compositional, “Lego-block” styles. Even with multiple inheritance, a field or class member belongs exclusively to one class, either its origin or an inheritor. Inheritance is linear, and alternative interpretations or overlaps require manual orchestration.

Human cognition, by contrast, readily sustains multiple interpretations of the same thing (being a buyer, a parent, an accountant, etc), and language naturally reflects this flexibility. Such flexibility, as we will see, is crucial for addressing the core challenges of the target domains such as contract-management.

By supporting multiple POVs, DCM keeps software systems transparent (“see-through”) as they grow and allows extensions or changes to be implemented without the effort increasing proportionally with system size — remaining instead scaled to the change itself.