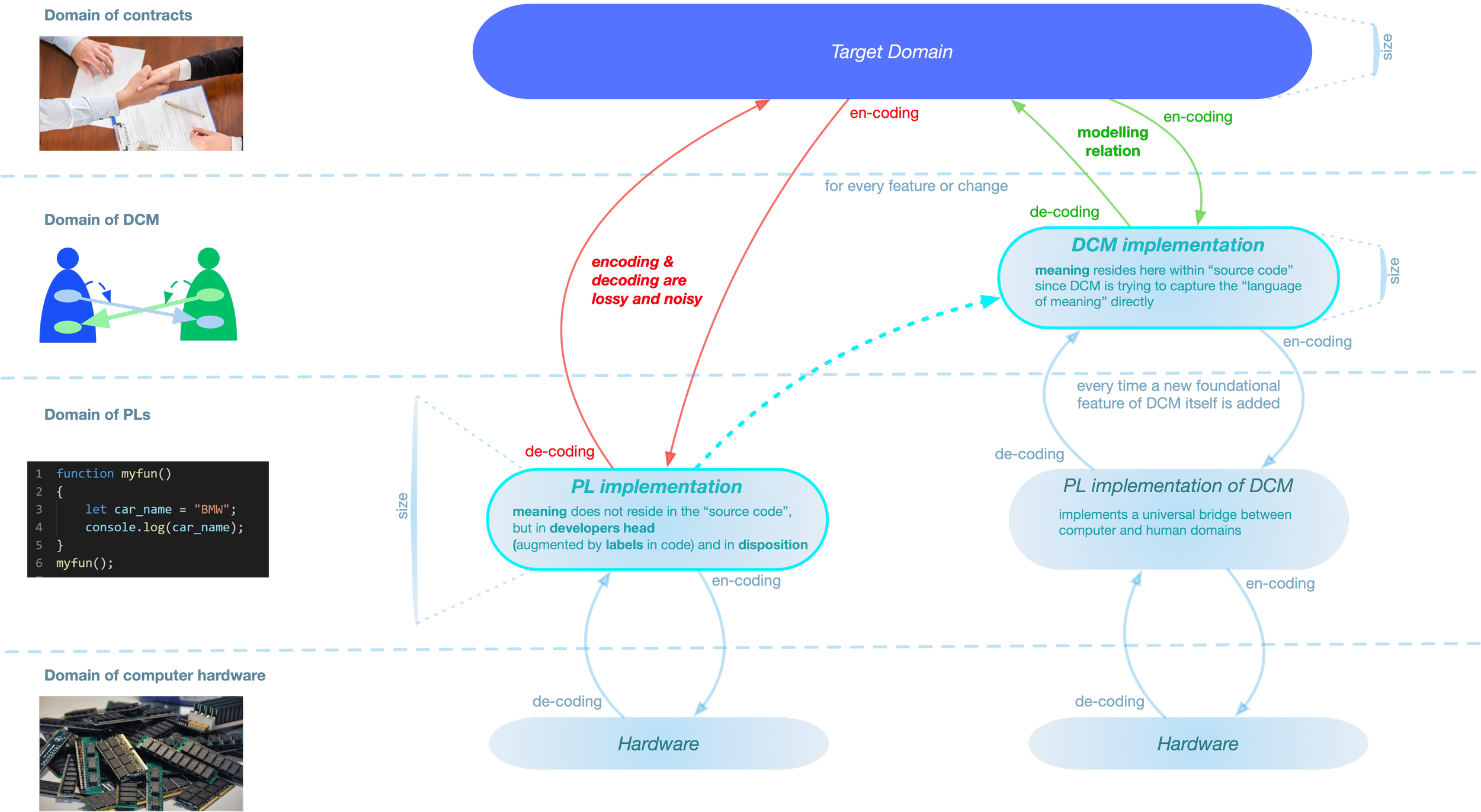

Suppose we want to create software that implements contract execution and management (for example, the settlement of a trade).

The traditional implementation path typically involves several layers, with the “top” layer being some programming language (PL).The problem with this approach is that the conceptual distance between the PL domain and the target domain (contract management) is too large. These domains have very little natural (inherent) “intersection”, as they are mostly incommensurable.

Two implementation paths

A more formal way to state this is to say that there is no modelling relation between the PL implementation and the target: the implementation is not a model of the target.

Note that, to the human eye, software code might seem like a model because humans automatically interpret labels and impose additional semantics on the software structures they see. But, as noted in the previous section, this additional semantics resides in the mind of the human observer, not in the computer.

As a result, every encoding of the target into the implementation loses most of the information and introduces too much noise.

Knowledge problems (SPOK people)

What worsens the situation is that every time we want to change something (e.g., meet a new requirement or add a new feature), we must perform encoding and decoding again. As a result, the errors from lossy and noisy encodings accumulate over time. Eventually, this leads to a software system that resembles a frozen collection of historical accidents and encoding idiosyncrasies.

Thus, in every organization that has built a large software system over many years, there will be a group of people with “secret knowledge.” These are the people who performed the initial encoding. Because each encoding involved many irrelevant degrees of freedom (introducing noise) while losing essential aspects of the meaning, it was up to those individuals — and the specific context at the time — to decide what the resulting solution would look like and how to decode it back to the target (i.e., what the software is actually supposed to do).

An outsider cannot guess what noise was added or what meaning was lost in translation, since this is — by definition — arbitrary relative to the problem being solved.

Furthermore, there is often no reliable path for such an outsider to follow to understand either the target domain or the (broken) Modeling Relation.

Frameworks over PLs, low code “platforms“ do not solve the problem

Even when software is built using frameworks like Spring or Domain-Driven Design (DDD), the framework itself operates at the level of a programming language (PL), and the developer still writes code with the same dispositional semantics ( described in the section on PLs) — key-value pairs, function calls, etc.

Naming conventions and other best practices are just that — informal guidelines with no formal grounding or guarantees. They are merely conventions between people, which at best provide ad hoc hints to the computer (e.g., via compiler extensions) about what additional constraints a piece of code should follow beyond the default semantics of the programming language.

So-called low-code platforms merely attempt to hide this behind pre-assembled blocks of code, which have very limited and ad hoc ways of being composed.

Because these solutions do not attempt to clearly define the target domain (i.e., what is the nature of the problems being solved?), they lack clear semantics. As a result, the same problem of lossy and noisy encoding persists.

Furthermore, low-code is no longer a programming language, but rather a form of parameterized software delivery. The productivity (the ability to generate new expressions, even those that have never been made before) and predictability that come with building through a proper language are lost, and the user is forced to learn the idiosyncratic technical encodings of a specific product.

The natural way to solve this problem would be to add an additional layer that sits closer to the target domain, allowing for encoding that does not lose critical semantics of the target domain while introducing minimal noise of its own. Such a layer would speak the business language directly — it would be structurally similar to it.

The tricky part is how to formalize such a domain and make it executable (i.e., interpretable) by computers. The DCM represents such an attempt.

Changing the basement makes many problems disappear

Switching the lens : Traditional challenges in building enterprise software systems assume a traditional foundation.

What happens to these challenges when switching to a different foundation (basement) ?

Could it be that the problem may have been misconstrued in the first place?

what is going on and why?

logging

monitoring / alerting

observability / tracing / telemetry

root cause analysis

correlation / cross-referencing

documentation

is software doing what it is supposed to?

unit testing

functional testing

integration testing

regression testing

performance testing

what if something goes wrong?

error handling

security

authentication / authorisation

risk

reliability

incident resolution / recoverability

But what happens to all of this if we shift the basement and express the application not in a PL domain, but in domain that aligns well with the target business?

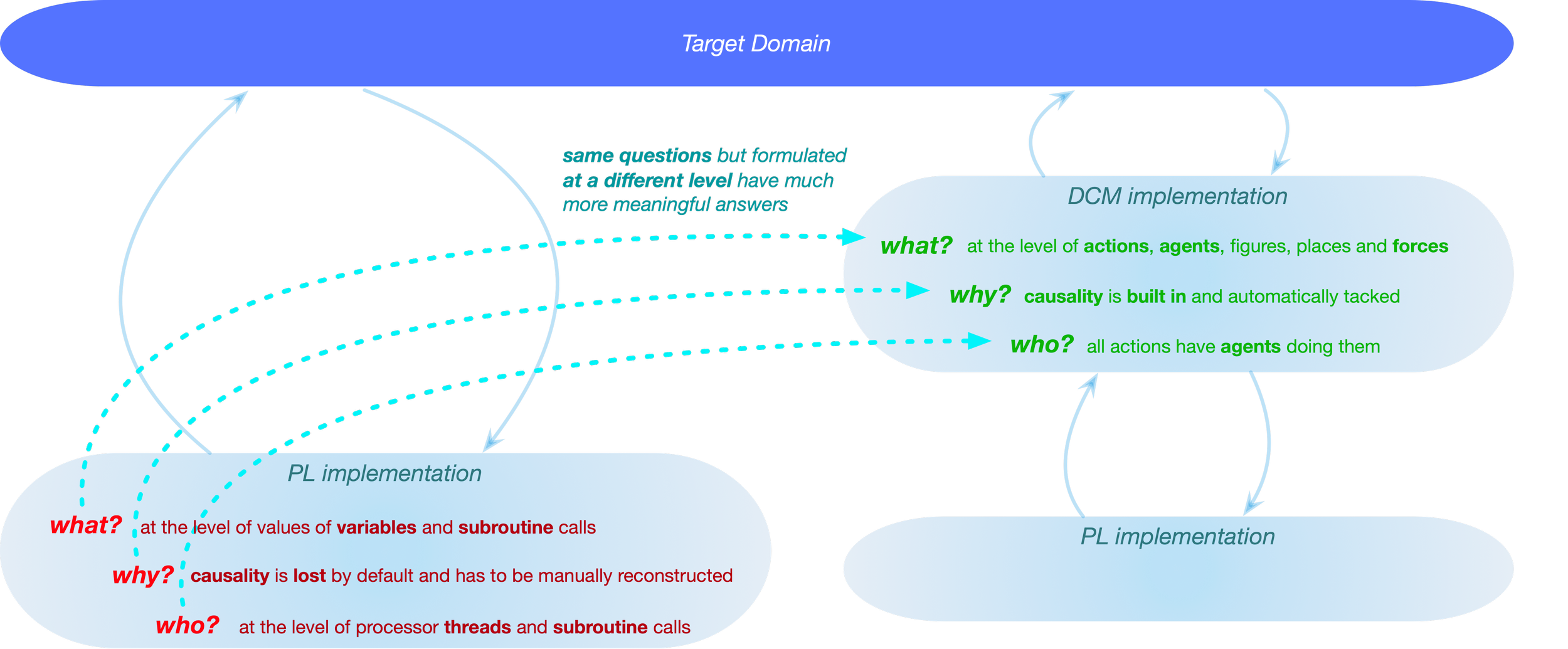

The primary building blocks of any programming language are variables—memory cells with human-readable nicknames. These cells can hold a number or a character, and that number could itself be a reference to another memory cell (as in memory dumps). Another primary construct is the function call: one set of instructions invoking another (as reflected in stack traces). All other constructs (such as object-oriented inheritance) are secondary, built on top of these two.

DCM (Deep Cognitive Models) has neither variables nor function calls in this sense. There are no stack traces or thread dumps. Instead, the application is expressed in terms of a cognitive domain—in terms of agents or subjects that engage in forceful action, making changes to configurations of space, such as moving figures from one place to another.

In DCM, the same questions—what, why, and who—are now framed entirely differently and, as a result, elicit entirely different answers.

Moving the coding from the PL level to the DCM level suddenly makes all those additional spectra of problems (arising from the transitional approach) either solved out of the box or addressed from a different angle, where they can be solved much more efficiently and with a fraction of the effort

A snapshot of what running software is doing is represented with a stack trace. Due to the incommensurability between the PL and target domains, each line in the stack trace has no direct relation to the target domain. Thus, instead of answering the question ‘why?’ about the behavior shown below, the stack trace represents encoding artefacts (technical noise) rather than what the system was doing from a business perspective.

The nature of the implementation domain shapes the questions that are consistently asked about software (that implements something in a target domain).

When we ask what is going on with the software (both at build time and runtime), the answers typically come from the programming language (PL) implementation domain—via thread dumps, stack frames, logs, and traces. However, all of these artifacts lack semantics of the target domain. Instead, they impose PL-level semantics onto answers.

As a result, such an implementation provides answers not about the target domain (what was actually being asked about), but about itself.

This is a bit like asking your colleague at the office: “Have you had lunch already?”

And getting the following as an answer:

“As of 12:35:45 AM, the calorie intake consists of: 21 grams of fat (of which 8 grams were saturated fat), 25 grams of protein, and 25 grams of carbs (of which 17 grams originated from sugar).”

This creates a niche: the need for additional software to bridge the gap between the PL-level (what the implementation knows) and the target domain level (what we're actually interested in).

See the next section elaborating on this with the example of logging.

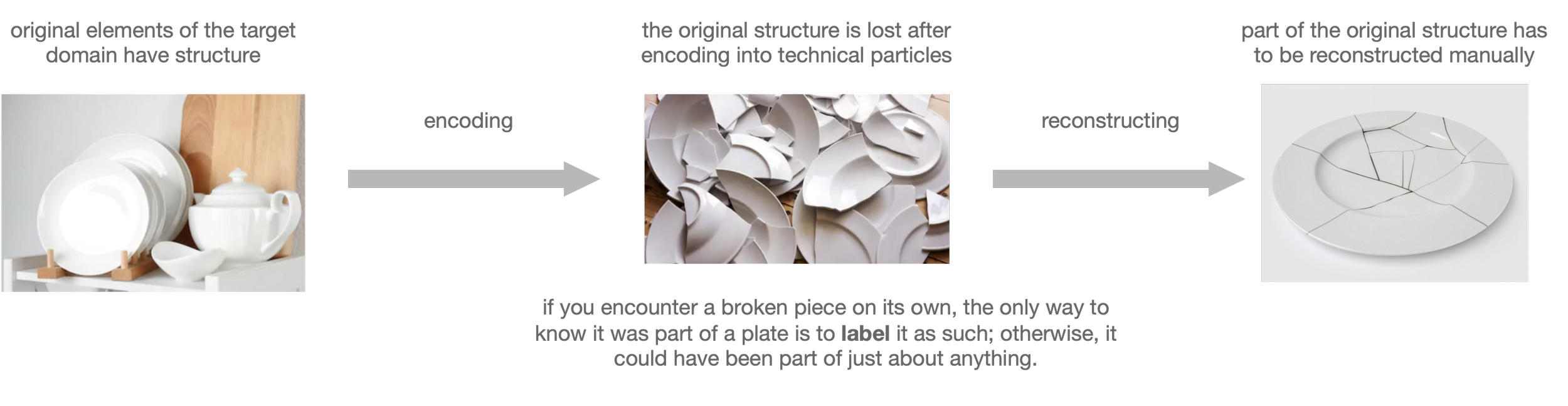

A form of ruthless Reductionism : the Humpty Dumpty problem

"Taking a hammer to a watch will give us a spectrum of parts .. these may be separated and characterised to our heart's content, but only by miracle will they tell us either how a watch works or how to make one.

This is because two things have happened : application of the hammer has lost information about the original articulated watch, and at the same time,

it has added irrelevant information about the hammer. What the hammer has given us , then, is not so much a set of parts as a set of artefacts."

Robert Rosen, Life Itself

Take logging as an example. It is essentially a time series of lines of text in idiosyncratic formats (neither natural language nor formal) produced by various components and layers of an application. Additional software is then required to collect these logs, transmit them over the network, receive and store them elsewhere, and enable querying using more idiosyncratic text patterns. All this effort exists solely to reconstruct what was happening at the time the log line was generated.

But a line of text—just like a sentence in natural language—does not contain meaning the way a box contains chocolates. Rather, it’s a "set of instructions to the brain" that only produces meaning when the brain has access to the proper context. Fully reconstructing the context in which a log line was produced is often extremely difficult or outright impossible—because that context is usually lost once the log line is detached from the application and begins to live and move on its own.

Structured and semi-structured logging are, again, ad hoc workarounds. They do not answer the foundational question: if a log has a structure, where does that structure come from? This set of problems has generated an entire ecosystem—log collectors, time-series databases, parsers—just to support the runtime life of logs next to a running application.

It is argued here that the answers given by DCM are at the level that the questioner actually expects and understands. That is, the traditional challenges of logging become irrelevant because the business activity the application was trying to report via a log line is captured directly—along with all the relevant context—by DCM. This capture happens automatically, without the need for explicitly written logging instructions.

From this perspective, the challenge of logging can be seen as an artificial problem—one that arises from the implementation domain (PL) and is inadvertently projected into the target domain (e.g., contract management). Once the implementation domain is aligned with the target domain, there is no need for "crutches," because no leg was broken in the first place.

This situation is just one example of a broader pattern of ruthless reductionism, where a domain full of inherent constraints is represented in a medium with too many degrees of freedom. In such cases, the original structure of the problem is lost, and enormous effort is required to manually reconstruct that structure in the medium (to re-create constrains artificially) —just to make it look like what it was supposed to represent.

The same phenomenon occurs in the field of application integration.

We call this specific instance of reductionism as applied to software development the Humpty-Dumpty problem.