Diachronic vs Synchronic view

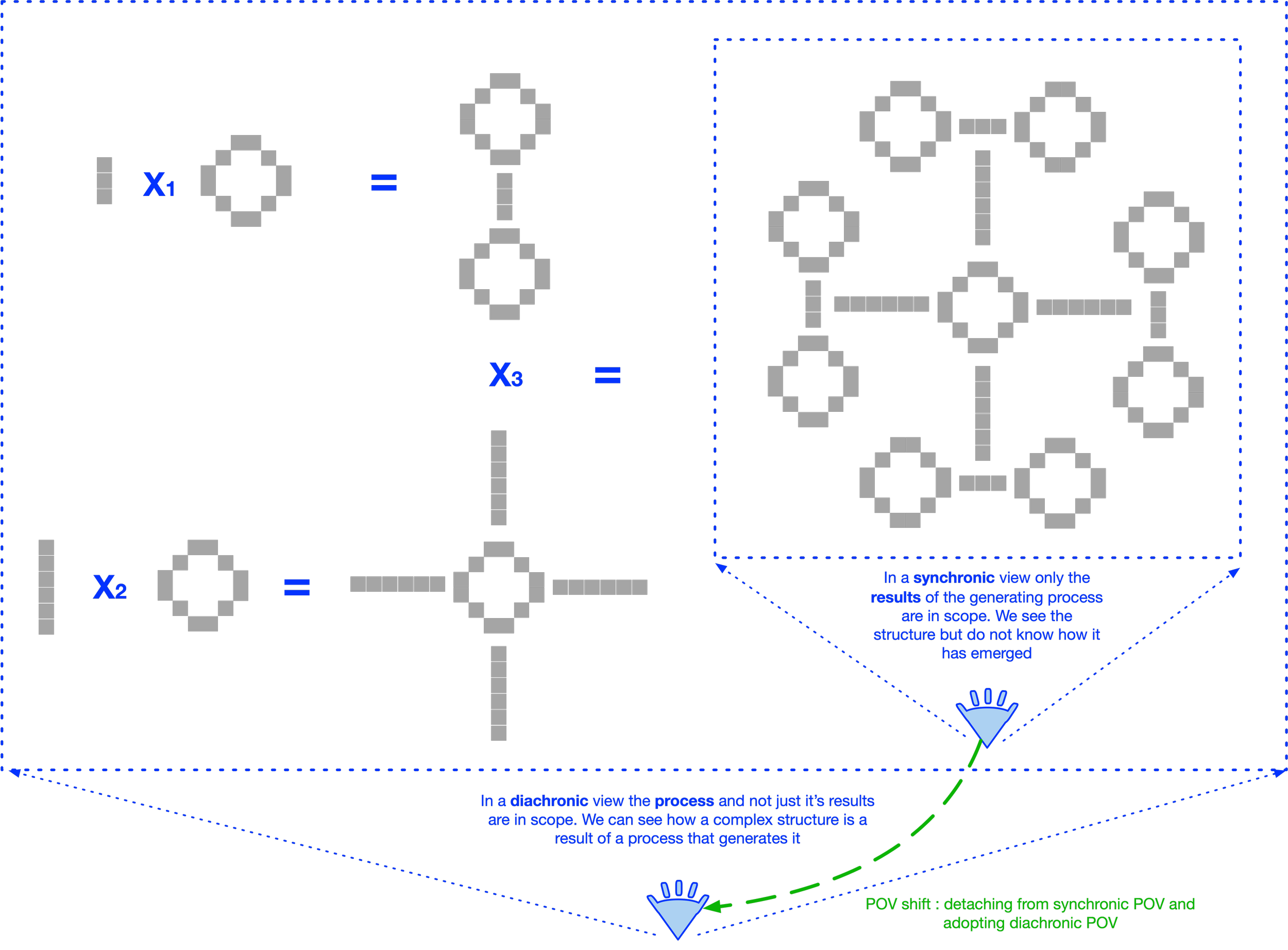

The usual approach to building software that supports a business is akin to taking a photograph: a snapshot of how the business operates is captured from the outside at a specific moment in time. In this sense, it is synchronic, as opposed to diachronic, which stretches beyond a single moment and captures a temporal dimension.

The time implied here is not just runtime (which is usually the mode in which software is designed to operate, though it does not represent it explicitly except in isolated cases, such as under labels like “processing time” or “timestamp”), but also design time, which is completely absent from the code.

This synchronic approach is easy to start with, as it does not require extensive analytic thought before starting to code. However, it results in an inefficient system—it is shallow in that it does not capture the rich causal structure of the business, but merely reproduces the isolated elements visible on the surface, simulating effects directly without taking into account the causal processes that generate them.

Ways to build a complex structure

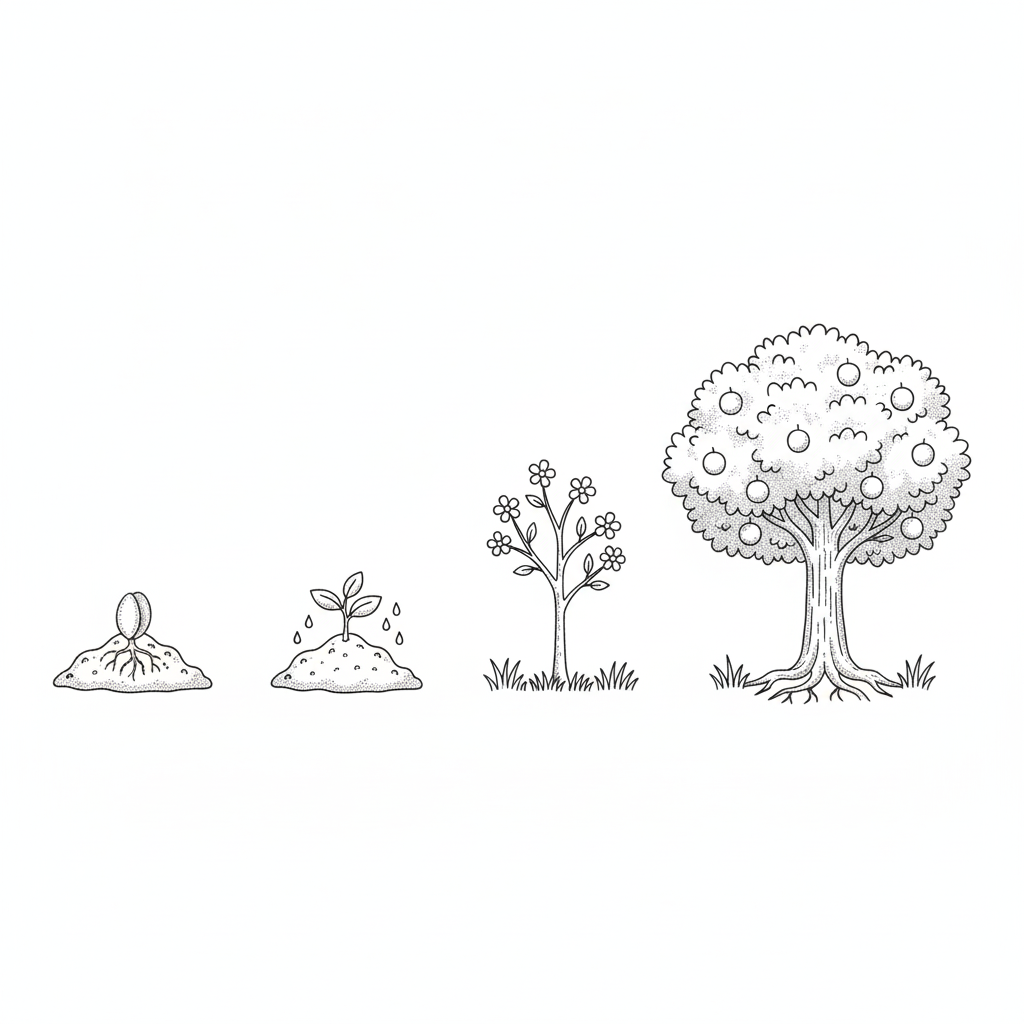

The actual way a tree gets is structure in nature is through grows process that starts from it’s seed.

In this sense, DCM reproduces the natural way of constructing a tree, capturing and preserving its morphological history—the logic by which its structure is formed. The trunk serves as the base from which branches grow, and each branch becomes the base for growing leaves, and so on.

Traditional approach is to build an already gown up tree synchronically, simply by adding elements together : attaching branches to the trunk, and then attaching leaves to each branch.

This method does not reflect the tree’s morphology; the relationships between branches and leaves are lost. All elements are treated as equal (having the same ontological and morphological status), being given in their current shape and “appearing all at once” or as “pre-existing.”

Object-centered versus ego-centered frame of reference changes the description of phenomena

The synchronic approach is also inefficient as it can not rely on the automatic replication of structure along the growth path (of change of the seed changes all the leaves in a tree) that the diachronic approach is based on. The efficiency of a diachronic approach comes from it's scaling factor - every time there is a one-to-many morphological relation along the growth path, this relation works as a lever in reducing the effort (the amount of work) required to build (grow) a structure.

Localizing a trunk in space automatically automatically localizes all its branches, and localizing a branch automatically localizes all its leaves. In this example, two scaling factors combine into a highly efficient “lever,” where a single action of moving the trunk automatially relocates all branches and leaves with it.

This efficiency arises from the tree’s topology, which is preserved when the growth process itself, rather than the artefacts it produces, is modelled.

Observer’s fallacy to detach

It is also an example of a very general observer’s fallacy—when an observer attempts to describe a phenomenon, they must choose a reference frame: what to take as the central coordinate system into which the phenomenon will be projected in order to measure it.

It requires considerable mental effort and flexibility for an observer to detach themselves from their own egocentric reference frame and instead adopt an external or allocentric frame as the center—to assume the reference frame intrinsic to the observed phenomenon rather than imposing their own upon it.

This detachment from the ego and the adoption of a new center is a non-trivial mental operation—a re-framing or a change of POV—which not only imposes a significant cognitive load but also requires knowledge of the target phenomenon. It is, in essence, a step toward objectivity.

A vivid example of failing to do so can be found in medieval depictions of animals, which are often anthropomorphized with human faces. As a result, what we see reflects more about the subject who was painting than about the object being depicted.

The DCM approach is fundamentally different. It is diachronic, relying on deep causal logic, where the relationships between structural elements and the processes that generate them play the central role, rather than the elements themselves in isolation. In this sense, DCM seeks to build a model of the target business domain, not just a superficial simulation animated externally like a puppet whose movements originate from externally attached threads rather than internally from within the muscles of its limbs.

The way to build with DCM is first to understand how something comes into being—what processes cause the appearance of a particular structural element, not just what the element is on its own, detached from the process that generated it.

If a different tree is required, the DCM approach would involve changing the seed or intervening in the growth process at the right moment—for example, by placing a barrier to limit the tree’s width or height.

The traditional approach would involve manually replacing old parts of the tree with new ones—subtracting the old and adding the new.

There is no guarantee that this synchronic method will produce a consistent tree, as it ignores the relationships between elements that ensure the whole structure “fits together”—that it is internally consistent and semantically sound. it ignores the level of reality of the tree that is situated below the level of it's visible artefacts (branches, leaves) - the tree as a morphological process.

This is a special case of the more general “sweeping under the rug” engineering problem — one that arises from ignoring certain dimensions of the target domain or limiting the scope of analysis.

Miinimizing effort in one dimension while disregarding what happens in others does not truly reduce effort; it merely shifts the burden into those ignored dimensions.

The total outcome might even be negative: as long as the target system remains confined to that single dimension, the optimization may appear to work.

However, once the system begins to operate across other dimensions, the optimization can introduce more problems than the unoptimized model.

Reducing complexity along the synchronic dimension simultaneously generates complexity in the diachronic dimension: it is much easier and faster to consume some sugar to reduce immediate hunger, but that will only introduce more problems over longer stretches of time. Shortly after the spike, one will become hungry again, while the lack of nutrients and damage to the circulatory system will accumulate.

As illustrated in the cash movement example in the section on modeling relations, traditional software development falls short by focusing on representing artefacts rather than capturing the processes and relations that generate them.

Holding things in mind is easier than trying to comprehend relations and processes that give rise to those things.

However, the cost of following this path of least cognitive resistance at any single moment in time is a cumulative increase in effort and the buildup of implementation debt, ultimately resulting in software that is brittle and opaque.

The main idea discussed here can be traced back to Pierre Curie and has played a prominent role in describing many different physical phenomena as well as to ideas of Gilbert Simondon. Here, we will touch only on the relevant tip of this iceberg, noting that this topic would require much more space for a proper treatment.

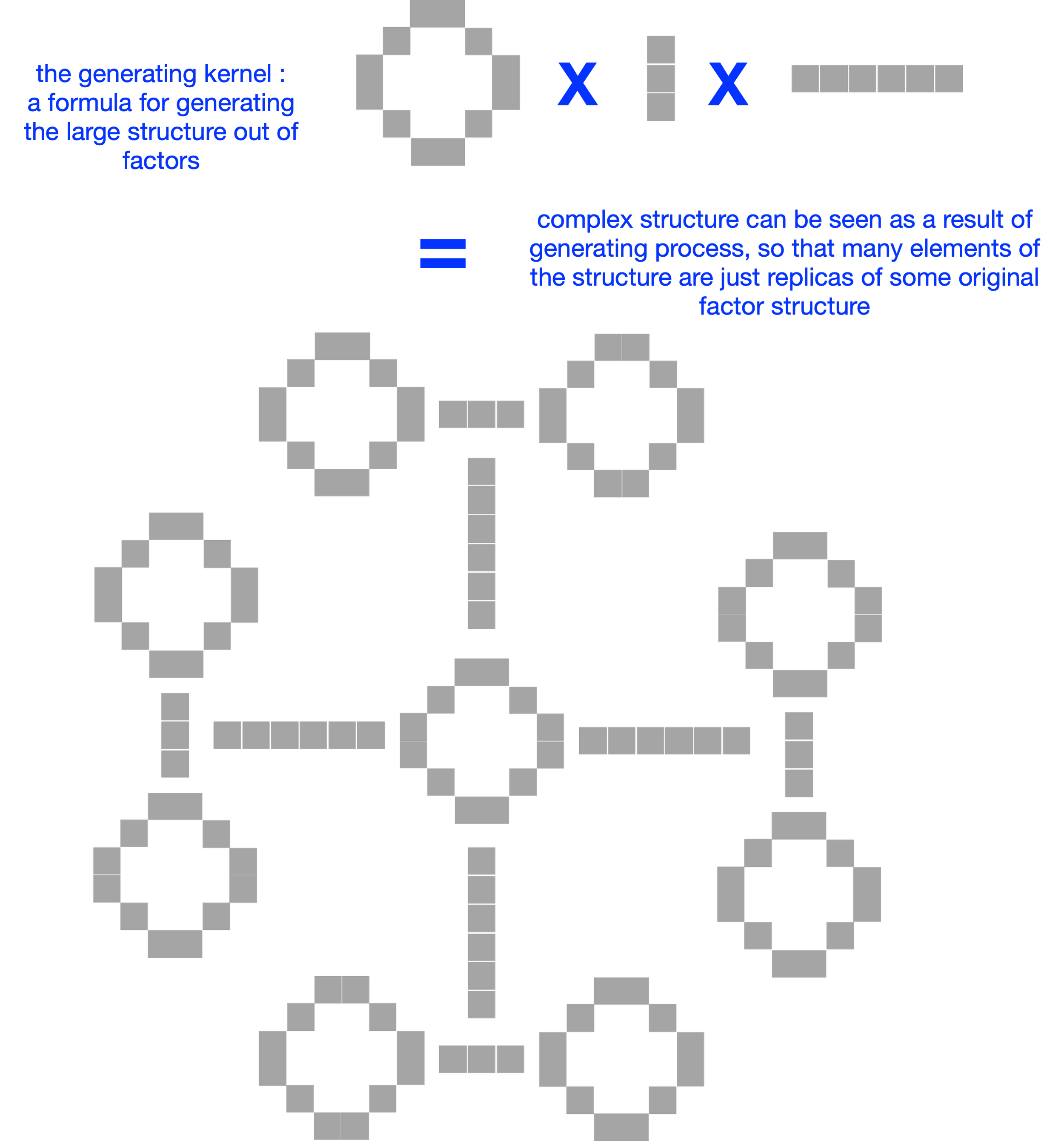

The logic of transduction and generating kernel

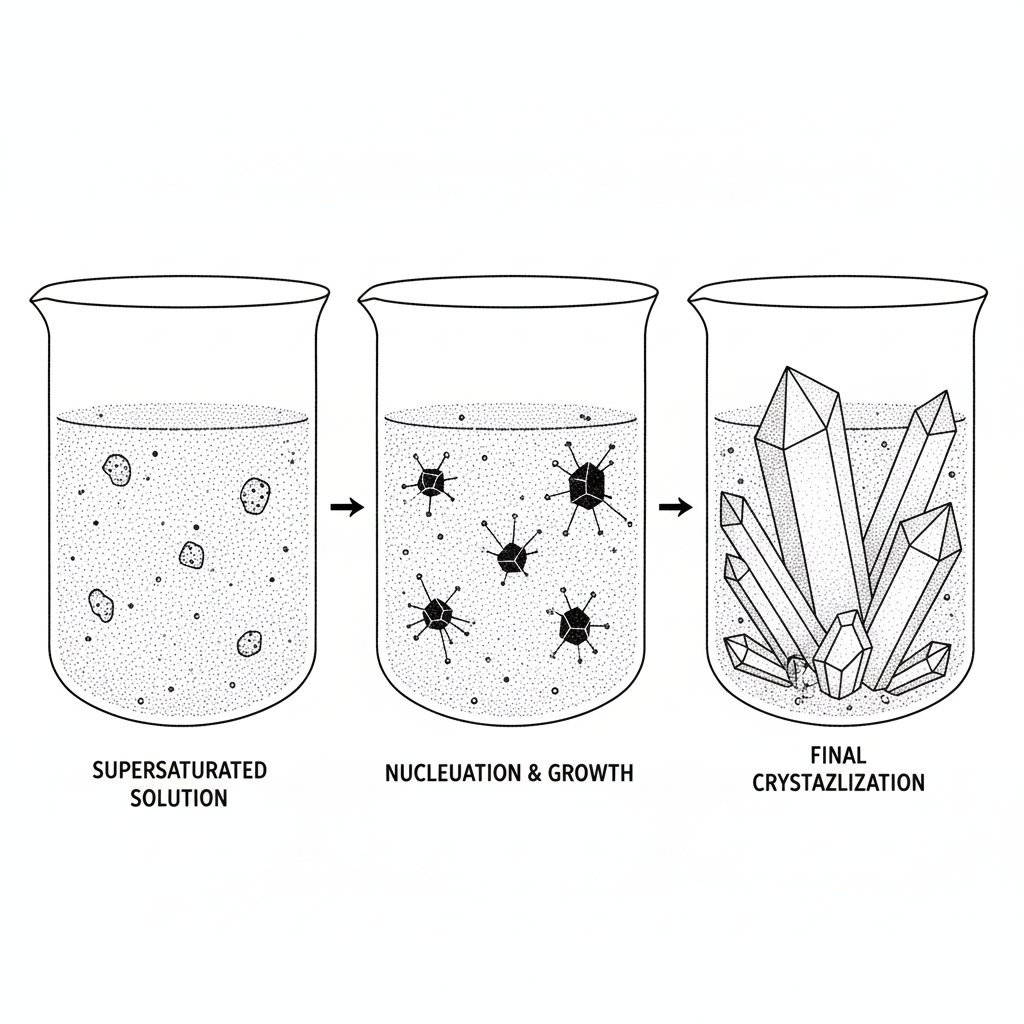

The logic of diachronic operation is that of transduction—neither induction nor deduction. This operation is frequently encountered in science, for example in the description of crystalline formation. Transduction describes the process of individuation, the appearance of structure.

DCM implements the individuation process as the relaxation of internal tension or inconsistency that arises when two systems at different levels of reality are composed into a single system.

Transduction occurs when two different orders or levels of reality, each internally consistent in itself, are composed into a single system.

By definition, for there to be a single system—and not merely two separate entities—there must be some form of interaction, communication, or linkage established between the two factors. The moment this communication is established, a tension arises between the two factors due to differences in their relative order.

Once composed, the system becomes internally inconsistent and must undergo restructuring to restore internal consistency—reconciling its order. This process often generates additional structure automatically through inference (pattern completion).

An example of this process can be found in crystallization, where the introduction of a crystalline germ into a metastable substrate composes a system from two different orders and triggers a relaxation process, in which the amorphous substance is incrementally structured into a crystalline form.

An example of this process in DCM is the introduction of the elaboration STOCK_OWNERSHIP → CUSTODY into the TRADE fibration, which creates an inconsistency between two levels of reality—one corresponding to CUSTODYand the other to the TRADE frame. This inconsistency must be reconciled through a relaxation process that results in the individuation of new agents (BUYER’s CUSTODIAN and SELLER’s CUSTODIAN), along with the individuation of additional subspaces, such as account structures for the BUYER and SELLER, and within each CUSTODIAN.

The recipe or formula for composing a system from heterogeneous factors to leverage this transductive structure-generating process can be called the generating kernel. This is the method of description that DCM adopts with instantiating frames into fibration.