DCM Theory (Glimpses of)

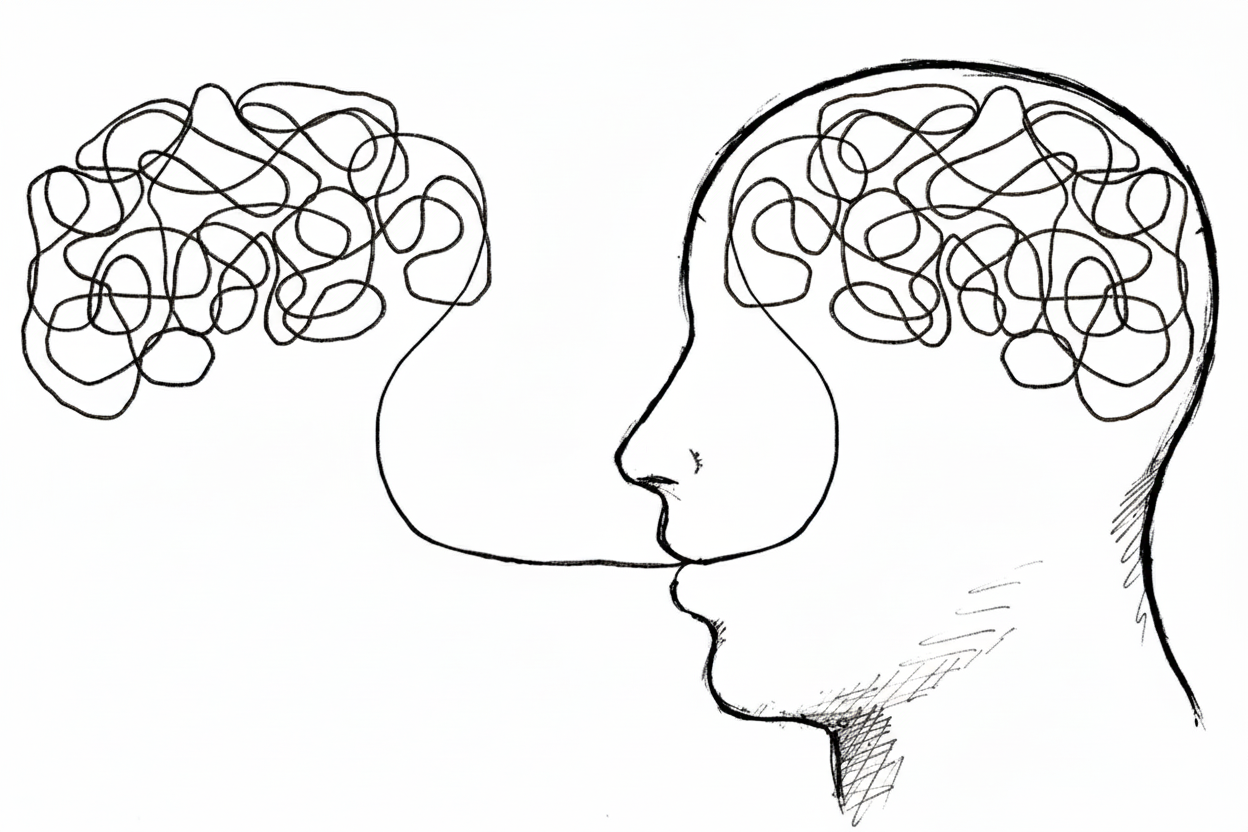

DCM is based on an extensive body of research in the cognitive sciences (especially linguistics), brain and mind sciences, as well as general systems theory. Unlike LLMs, it is not concerned with spoken or written language, but with the “language of thought.”

DCM is a theory of construal, conceived as a formal model that can be executed as software. Construal may refer to the process of conceptualizing something, or to the results of that process. Construal is not intended to represent an objective model of the world, but rather to provide enough grip on the world to allow the subject to act toward achieving their goals by deploying this construal in a specific situation. DCM itself is based on a smaller, but more generic core — the Frame Vantage Theory (FVT).

The central notion in DCM is the concept of a frame, and the idea that the same content can be framed in multiple, alternative ways — that is, the same content can be captured simultaneously by many different frames, overlapping on some parts of the content and complementing each other on others. The latter is known as the collage mode of composition — a model of building larger structures from smaller ones, rooted in the principle of superposition.

Frames correspond to categories, and schematization—the process that produces frames—corresponds to categorization.

Space

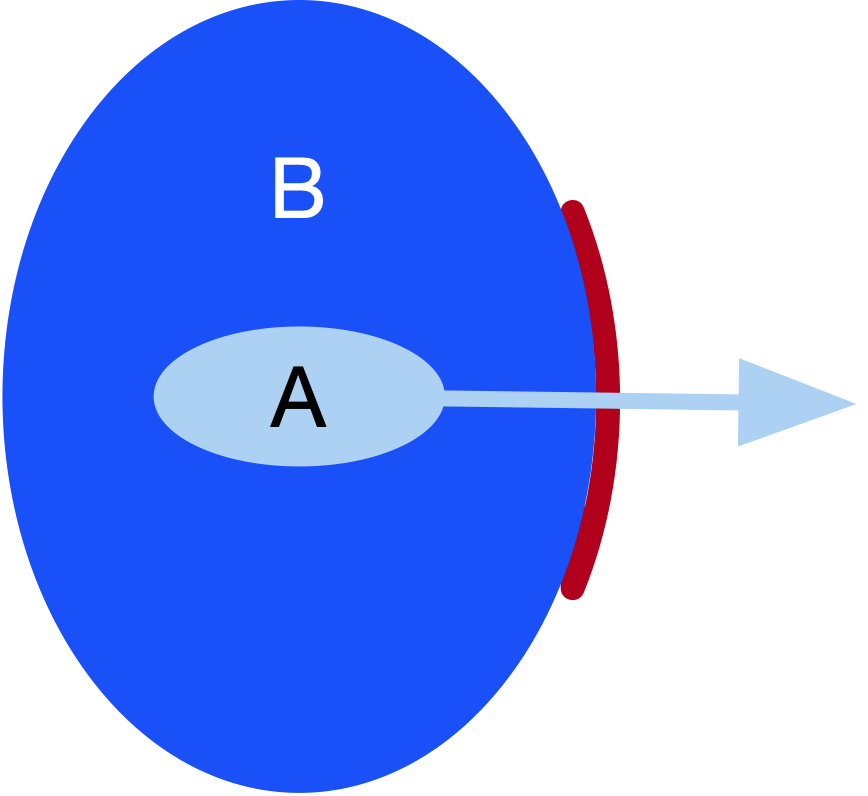

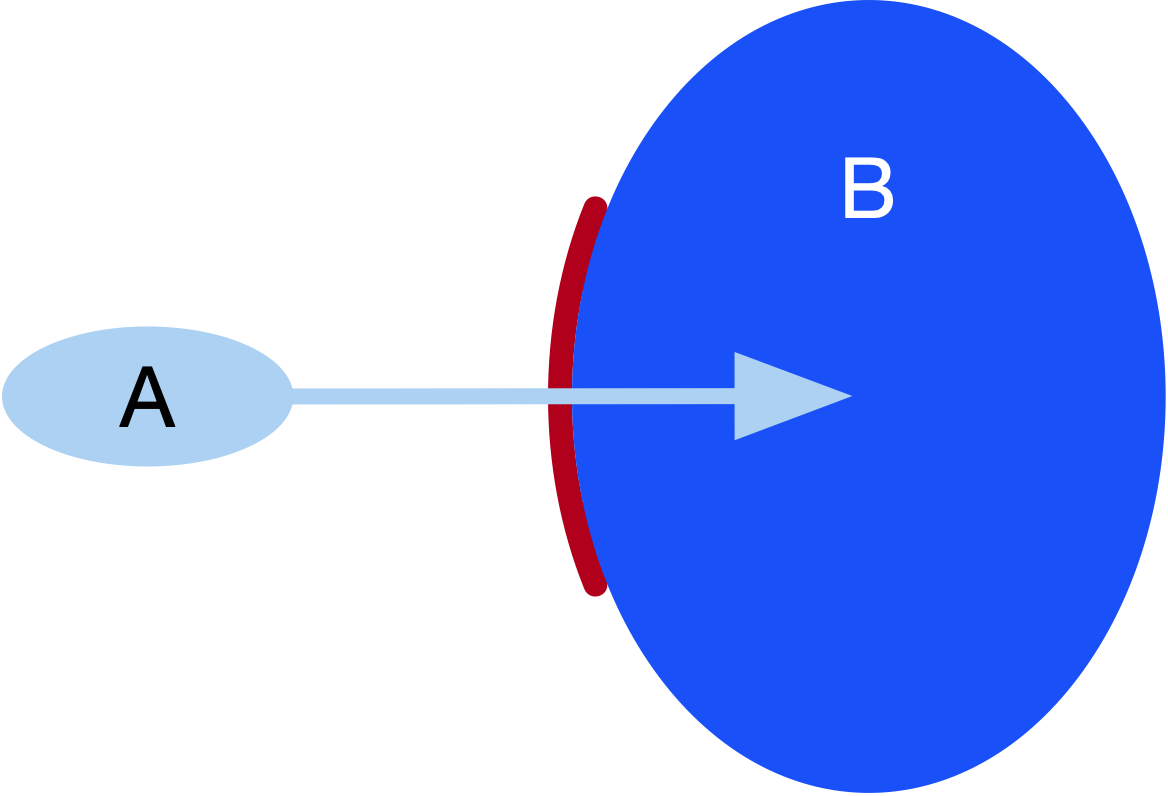

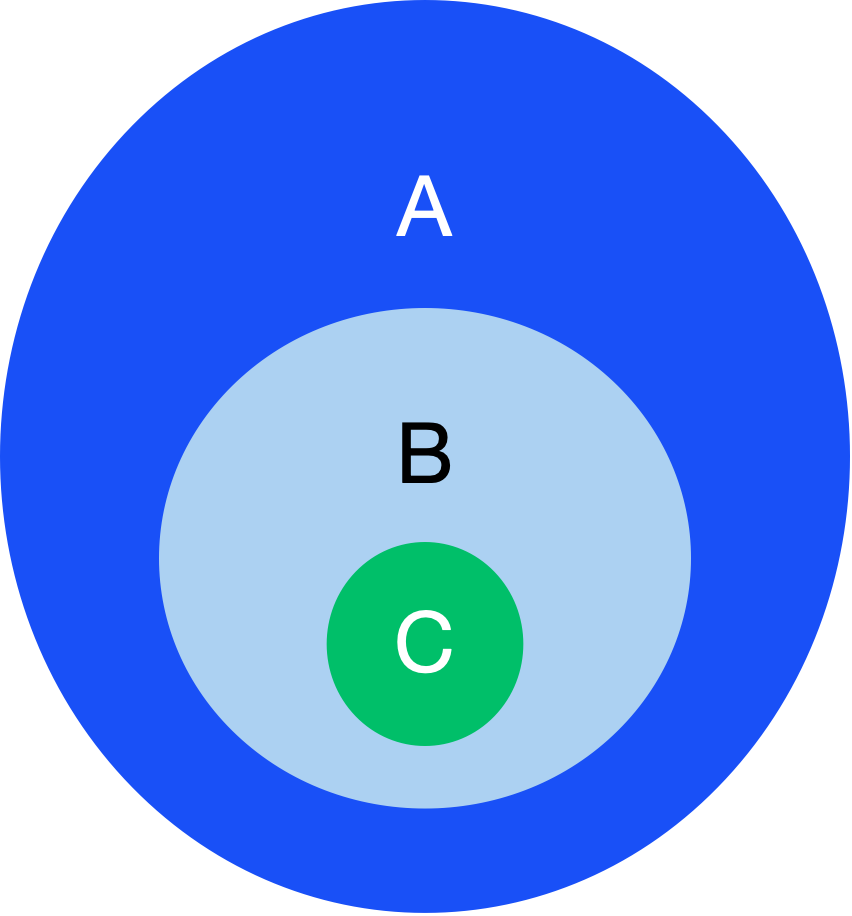

The structuring mechanism in DCM is based on the (abstract) topology of spaces, with the central relation between spaces being that of containment—for example, an ACCOUNT space is contained within a CLIENT space, which is contained within a BANK space.

Both elements—the spaces constituting a background and the figures—are roles within the frame. The semantics of a frame is such that all of these elements are essential to the frame, and removing any would render the frame incomplete and meaningless.

A frame is basically a relation between all of the roles, so one role cannot exist without all the others and vice versa. They are mutually defined, and it is in this sense that a frame represents a bootstrapped space.

Time

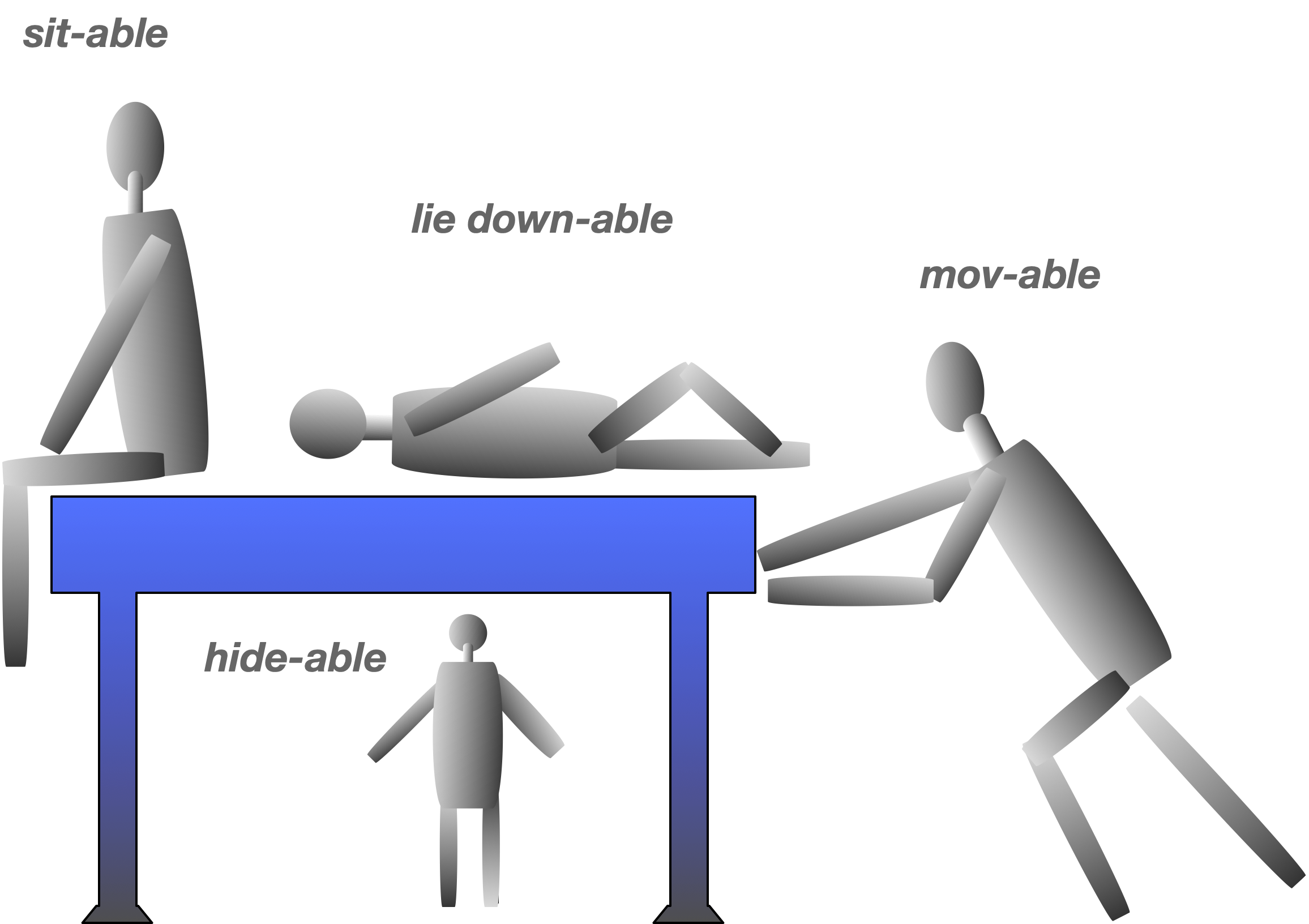

Frames serve as snapshots, each providing enough detail to enable certain specific aspects of action (affordances), while lacking the detail required for others. Each frame resolves only those details necessary for a specific action, and in this sense a frame localizes the content along its dimensions (this will be expanded upon later). To execute a complex action, which is construed out of simpler ones, one must deploy a number of different frames, which themselves must be bound together in specific ways—forming a "frame bundle".

Frames are usually bound via shared content that they construe—so what sanctions the binding of frames together is not just the cognizer deploying them but also the target, which provides the shared content on which these frames overlap.That is also one of the theories of binding in real neural networks in the brain: binding by synchrony.

As will be described elsewhere, there is a possible mapping of DCM and FVT onto the functioning of neural assemblies in the brain, such that each frame would be implemented by a dedicated assembly, and their relative firing phases would constitute the bindings between frames—similarly to the bindings for each fibre in any construal built with DCM. So it is through the overlap in the target content that frames relate to each other.

The frames themselves, and the way they are bound, can be described as vantages with FVT.

Having dynamics implies temporality, so a frame necessarily has a temporal dimension arising from its dynamics.

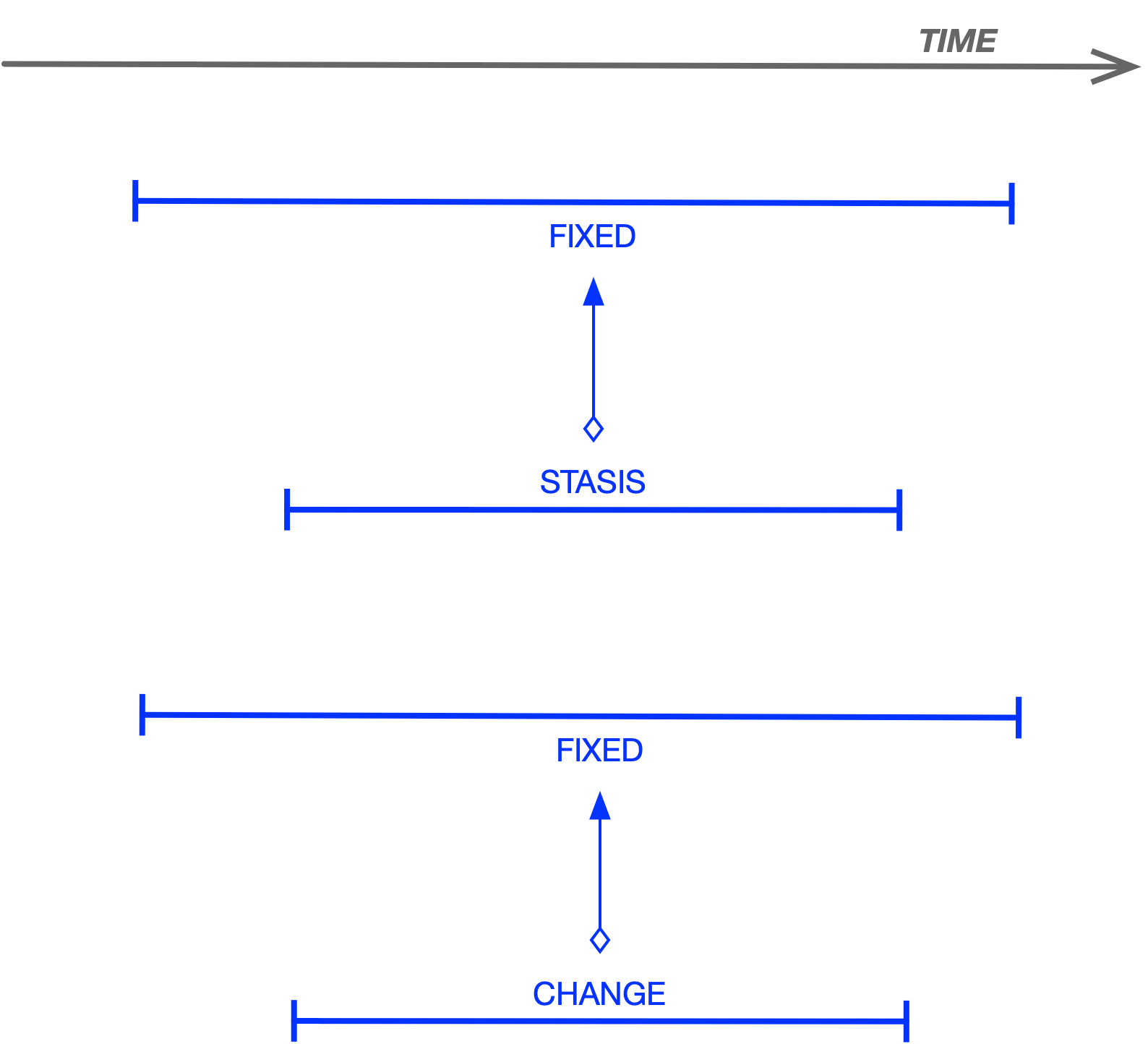

Even the figure/ground construal alone already implies a minimal temporal structure: the background is construed as existing within a temporal span that embeds (contains) the temporal span within which the figure is construed. The former temporal span is called FIXED, and it corresponds to the temporal span of the construal itself—i.e., the temporal interval to which the frame applies. Outside of this interval, a frame says nothing.

Definition of a Frame

A frame represents a single figure/ground construal and partitions the content (being construed) into two parts: the background, which is static and does not change, and the figure, whose change can be tracked against the background. One can not exist without the other.

There can be a few figures within a single frame, but never more than just a few, as this relates to the fundamental constraint of cognition on which DCM is built. The background is usually given some structure (unlike the figure, which usually lacks structure or whose structure is relatively simple compared to that of the background).

Similarly, a frame would cease to be meaningful if any of its essential elements were missing— for example, removing the SELLER from the TRADE frame, or removing the figure being released from a RELEASE frame.

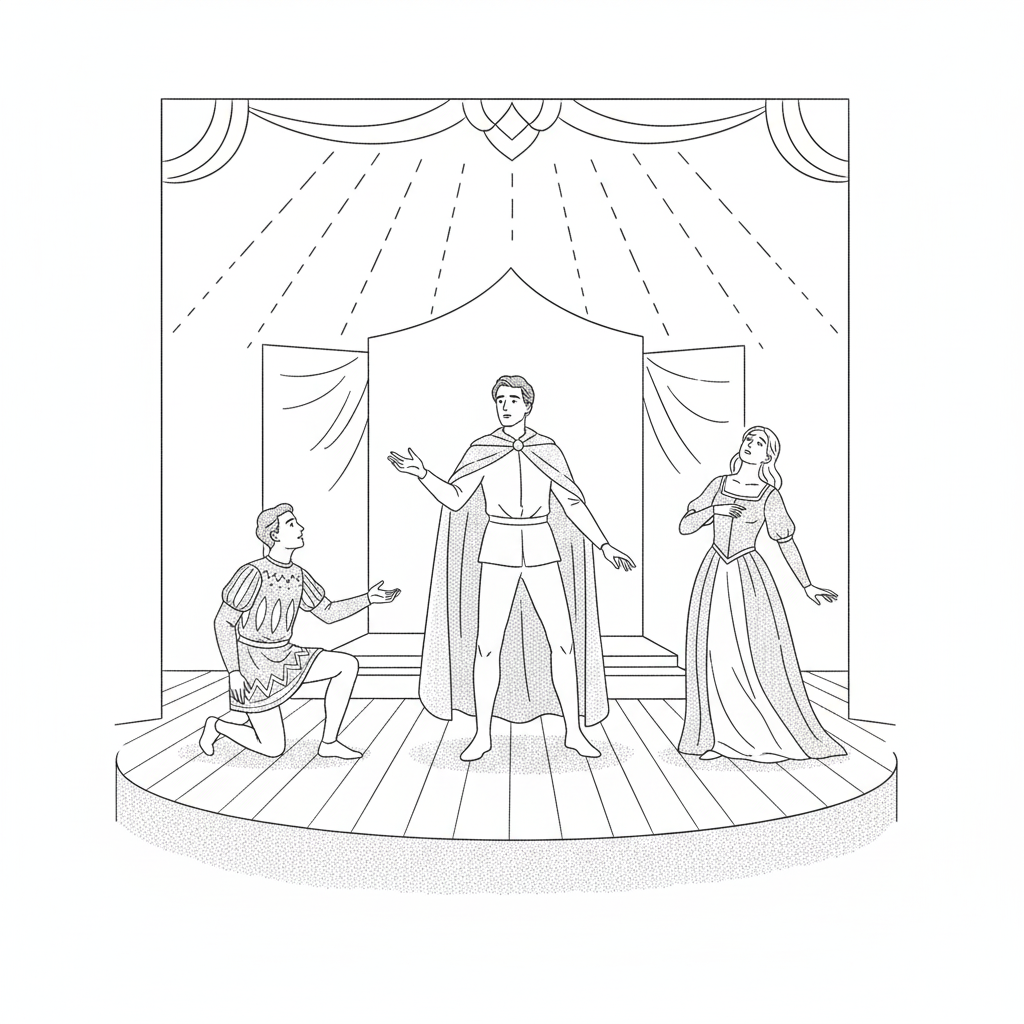

Having multiple frames corresponds to having multiple scenes, where the same actors may play different roles across different scenes, thus developing their narrative arcs. Since each frame has a fixed setting, it allows only for certain actions—those made possible by the setting—and not others. As a result, most plays (or mental construals) involve changing the setting or at least shifting the perspective—this corresponds to switching frames.

Informally, the notion of a frame can be seen as analogous to a scene in a story or a script for a scene in a play. It has roles (to be played by actors when the play reaches the stage), these roles involve specific actions, and it includes a setting—the background against which the actors’ actions unfold.

Everything that happens within a scene is internally connected, so the scene would become incomplete or lose its meaning if one of its elements were removed.

Frame as affordance

BC_IN and BC_OUT are construed as CAPTURE and RELEASE when the figure itself is passive while the spaces it crosses are agents, being the source of force for the border-crossing action.

A frame thus has inherent dynamic content construing a goal-directed action —and in this sense, a frame is about acting (doing), not about depicting or describing an objective (cognizer-less) reality.

Needing to act is the raison d'être for the existence of a frame (which is the result of a process of schematisation after exposure to a set of experiences that turned out to have the same action patterns in them). Thus, knowing what one wants to do is a prerequisite for coding anything in DCM—unlike coding in PL, where one usually starts with static and technical artefacts like data structures, interfaces, databases, and message schemas, etc..

All other elements of the world that are not relevant to enacting this goal are effectively made invisible to the organism—they become transparent. The deployed frame acts like a lens, with the implementation domain being the frame and the goal being the target domain. The frame will be efficient for achieving the goal when the frame establishes the modelling relation with the target domain.

Having elements in the frame that are irrelevant to achieving the goal makes the frame noisy and inefficient. This is why, when one first learns to perform a novel action, such as riding a bicycle, there are initially too many elements to process, which overloads one’s action control.

With time and practice, irrelevant elements are pruned from the cognitive field of view, making it narrower and narrower until only the relevant degrees of freedom remain - the ones that directly control the action. When the field of view becomes sufficiently focused, with a concrete figure/ground construal, the action becomes efficient and reliable in achieving the goal. This process is essentially frame formation, or schematisation.

It is important to note that DCM deals with the process of conceptualisation, not schematisation as such. Conceptualisation occurs once a stable repertoire of frames has been developed to deal with the world, which is typically the case in structured domains such as financial operations.

Dynamics

Just having these two elements - spaces and figures - is already enough to describe most of the dynamics, including those that occur in a trading domain, for example. Having spaces that are static and figures that can move immediately creates the potential for figures to move from one space into another - to cross boarders of spaces :

a figure crossing the border of a space in the outbound direction: BC_OUT, and

a figure crossing the border of a space in the inbound direction: BC_IN.

DCM is built on a closed class of morphological primes, of which these two are the most important ones within the target domain addressed here.

Note that BCIN and BCOUT are duals. However, due to the asymmetry of the time axis (temporal dimension), many phenomena are interpreted differently when the axis is flipped. Therefore, we use two distinct primes instead of reducing these phenomena to a single construct and mirroring it along the time axis to derive the other.

Frame as a story

Each frame represents a specific affordance, directly at the expense of excluding all others—just as, when an action is to be taken, one stops considering all the other possible things one might do in the same environment.

One of the fundamental constraints on cognition arises from the fact that only one action can be performed at a time. This limitation stems from being embodied in a body with specific limbs and muscles that have flexible but pre-defined degrees of freedom, which is itself embedded in a three-dimensional world. This bodily space of actions shapes how action is cognized, while the dynamics of the body also shape the dynamics of the brain. From an evolutionary perspective, it would not have made sense to expend resources on speeding up a nervous system that could operate orders of magnitude faster than the body could move. Therefore, the motor neuronal system only needs to run fast enough to control muscles, which have a limited contraction speed.

Since each action requires its own specific motor program, having a fixed number of limbs that can move at a fixed speed means the body can efficiently control only one action at a time. The deployment of a specific action schema—engaging neural assemblies in the brain—frames the organism’s body and the world as perceived by the organism to suit that action. This deployment orients the organism toward achieving a specific goal attainable through that action.

The notion of a frame has been around for a long time in theories of mind, brain, cognition, and psychology. However, it has generally remained an abstract concept, lacking the detail necessary to make it formal and executable in computational systems. This is precisely what DCM aims to achieve.

Research in the theory of concepts also falls into this category. To reduce this line of inquiry to a practical bottom line: whatever solution is proposed must incorporate dynamical capacity (i.e., it must be a process and encompass a temporal dimension), must serve as the underlying mechanism for language (as described in cognitive linguistics), and must be flexible enough to account for how the mind can bend reality in pursuit of its goals.

From the start, none of the above can be effectively captured using the structures provided by general-purpose programming languages (as argued elsewhere on this site). DCM is developed as an attempt to realize such a system.

This is fundamental to how language works in deriving (or inferring) meaning—when one hears a sentence like “I paid too much for this,” one does not only construe what was explicitly mentioned in the sentence—the amount being paid and something that has been paid for. The hearer automatically evokes the full frame, which also includes a role for the seller. The sentence does not fix the seller’s role, meaning this role is construed generically (see the relevant section of FVT on the degrees of fixing). This is often called a pattern completion process.

Note the each frame will have it’s own roles, so it has it’s own isolated space independent from any other frame spaces unless explicitly construed so using embedding operation.

The prime frames CAPTURE and RELEASE are considered prime because each consists of a single prime change or event—either BC_OUT or BC_IN. Such a change is construed as durative, thus spanning a temporal interval. This interval is called CHANGE for prime changes, and it is embedded (contained) within the FIXED temporal interval.

For frames that do not construe a change but rather a static configuration—or a snapshot in which a figure is localized in some location (such as CUSTODY)—two temporal spans are involved: FIXED, corresponding to the span of the frame, and STASIS, corresponding to the span within which the localization holds.