Building Construal with Frames : Fibration

Fibre

In cognition, almost everything is relative—for example, what is considered schematic from one point of view may be specific from another. A dog is schematic for a Spaniel but concrete for a Mammal. Thus, a frame can appear schematic when seen in isolation, but more specific when considered as an element of a larger construction.

When any elaboration is made to a frame within a specific context, we call the elaborated version of the frame a fibre (by analogy with fibre bundles in topology - see the section on mathematical underpinnings). This is an instance of the frame, but not in the sense of being part of the real world or objective reality (the latter will be referred to later as the runtime reality level). The frame is instantiated to the level of reality of the context in which it is used, which can itself be highly abstract when contrasted with the real world. The fibre (frame instance) thus becomes a constituting element of the construal (representation) of this level of reality, since we perceive that reality through the prism or lens of the frame.

Fibration

Levels of Reality and Aristotelian Causes

Embedding

The process of composing frames from other frames and layering frames over one another results in a structure that is not itself a frame. For example, a TRADE construal that enables the execution of a settlement is not a frame in itself. It is composed of many fibres and is therefore technically a fibre bundle or a fibration (see the Mathematical Underpinnings section).

The meaning (raison d’être) of this ‘fibration‘ construction is to shape some target content in order to afford specific actions, which is basically the definition of the term construal. Technically, the concept of construal is implemented in DCM by means of a fibre bundle construction, or more concisely, a fibration.

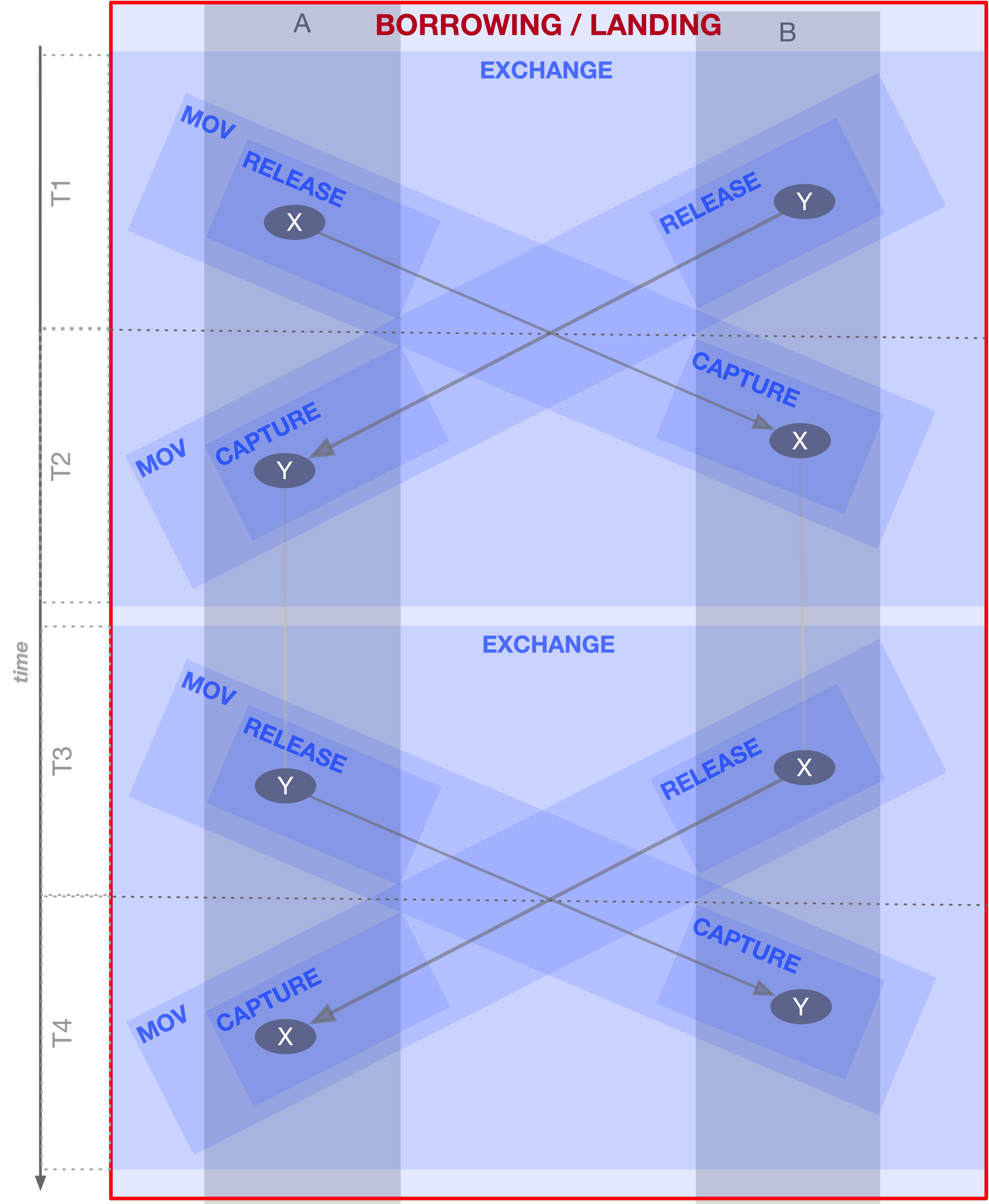

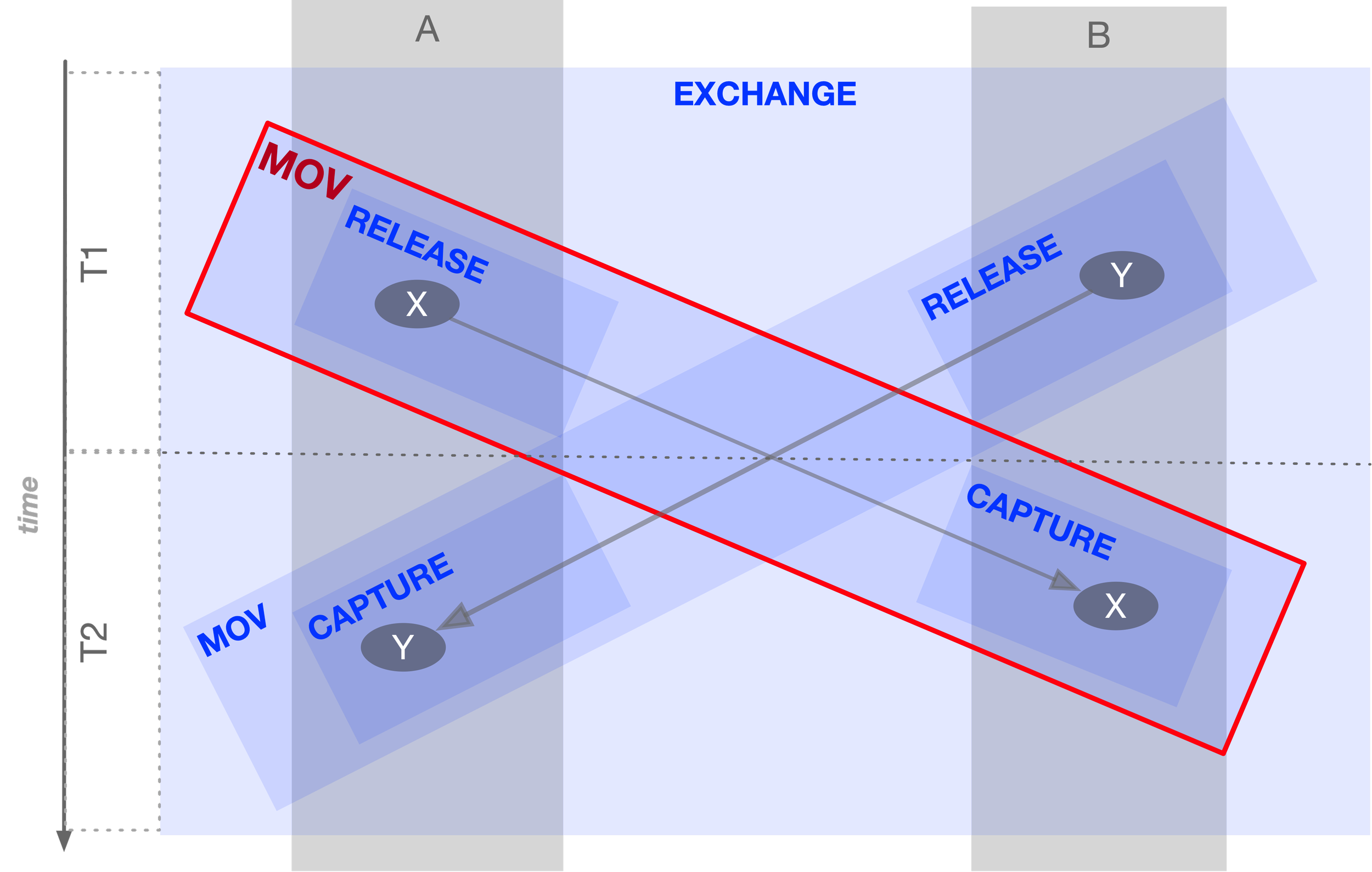

Because the same frame can appear multiple times within such a construction under different fibres, it makes sense to call it a fibre bundle rather than a frame bundle. E.g. the same frame MOV appears twice in the definition of the EXCHANGE frame.

This fully parallels the mathematical definition of a fibre bundle. For simplicity, we will refer to it as a fibration (the distinction between the two is not relevant here).

Employing a frame A as a fibre when constructing frame B adds an additional POV on the same target content (where A and b overlap), affording new actions while also adding a common dimension shared with other fibrations that contain the very same frame as a fibre.

If the same frame A is used as a fibre in another frame C, then A can serve as a common denominator — the shared point of view — for B and C.

Additionally, each frame comes with its own extent (the content it captures), so choosing whether to deploy A or B also determines which content we are operating on.

For example, the MOV frame will capture both a stock trade and a stock transfer, whereas the TRADE frame will not capture the latter. Hence, choosing which frame to deploy is also choosing which content to operate on.

A construal is built incrementally by adding fibres, and it has its own internal structure—derived from those fibres in much the same way that a 3D object is reconstructed from multiple 2D projections.

Fibration itself is a structure that is not consciously entertained or reflected upon by the mind; the mind can only reflect on specific frames. The reason this underlying structure remains invisible to the untrained eye is precisely because it is not the result of a schematization process— it is not a frame. Rather, it represents a mechanism that enables the deployment (or application) of frames.

Operating in the background, it does not require explicit attention; it works automatically, and thus remains out of focus. The internal workings of this structure will be addressed in a separate piece.

A human writing DCM code, does not need to reference this structure directly, as all necessary construction steps can be carried out through cross-referencing frames.

As a result, the structure remains an "invisible" backbone that supports these operations (a framework that holds a set of frames together).

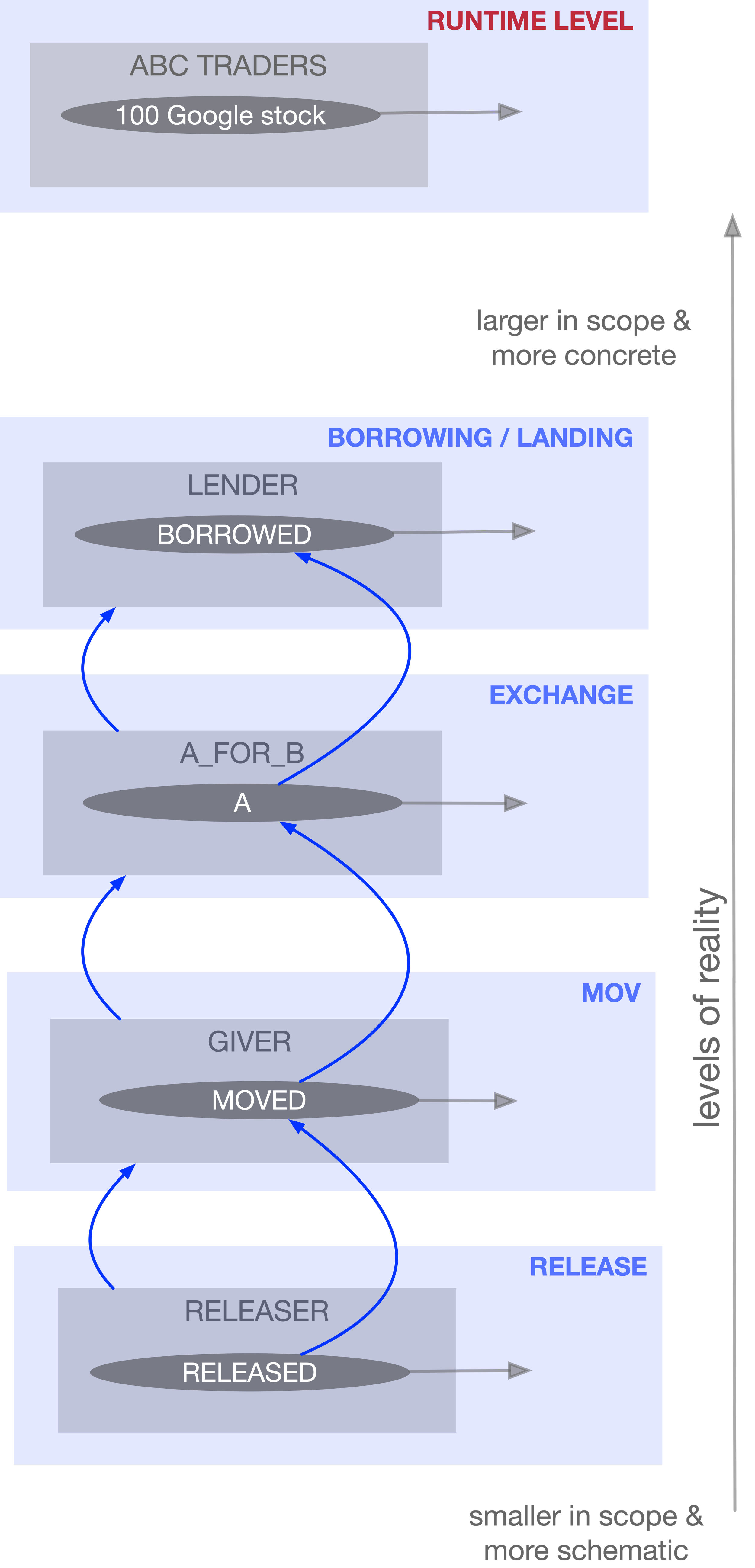

We can still refer to the resulting fibration as a TRADE construal because the TRADE frame holds an ontologically privileged status. It serves as the most concrete level of reality, grounding all other fibres by instantiating them through its elements. In this way, the TRADE frame acts as the surface level of reality onto which not only its components (like MOV) are lifted (i.e. bound), but also all the additional fibres layered over it, such as CUSTODY, REQUEST_REPLY, and others.

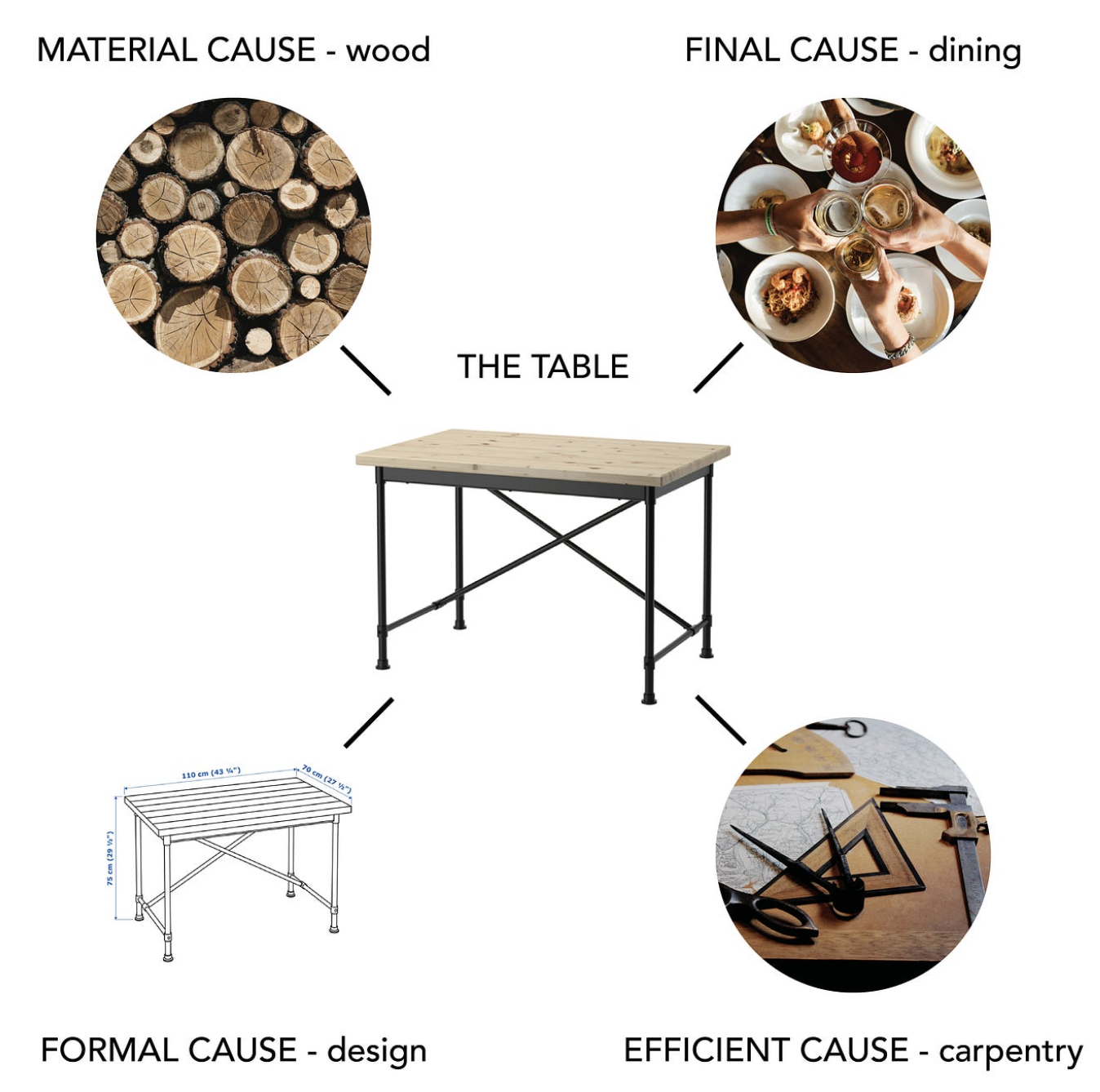

The TRADE frame, being the surface level of reality, represents the final cause in Aristotelian terms (In Aristotelian philosophy, the final cause refers to the purpose or end for which something exists or is done).

Any element within the construal (e.g., a RELEASE fibre that represents a CUSTODIAN sending a settlement instruction to a CSD) can be traced upward to this surface level.

A fibre is a copy of a frame that functions as a part of another frame; the latter is called the embedding frame, while the former is the embedded frame. A fibre is thus an instantiation of an embedded frame at the level of reality represented by the embedding frame. We will return to the notion of embedding in the section on Frame Vantage Theory (FVT).

As noted earlier, a frame defines its own space, so the fibre corresponds to establishing a correspondence between two spaces—the mapping from one space to another. However, this mapping function is not symmetric: the embedding frame must cover the same content as the embedded frame, but not necessarily vice versa. Thus, we can treat the frame instantiation operation as embedding the space of the fibre's frame (the embedded frame’s space) into the space of the fibration, although it is possible for the latter space to be constructed from copies of the former.

Because the result of composition in DCM is composition-path-agnostic, or path-independent, a TRADE frame can be composed of two RELEASE fibres just as it can be composed of two MOV fibres or a single EXCHANGE fibre.

When a RELEASE frame is embedded into a MOV frame as a component, the content of the RELEASE frame becomes more concrete — it is elaborated by the MOV frame. At the same time, the MOV frame is itself composed of the RELEASE frame, and is thus also elaborated by the RELEASE frame in turn. In this way, composition is a mutual elaboration.

When the content of the RELEASE frame is elaborated by being bound to elements of the MOV frame, we can say that the RELEASE frame is lifted to a higher level of reality — going from something more schematic (abstract) to something more concrete. In this sense, the level of reality of any specific RELEASE fibre is more concrete than that of the RELEASE frame as such, because the fibre is bound to elements of the MOV frame, which are more concrete.

For example, in the EXCHANGE frame, we have two MOV fibres—each is an instance of a MOV frame, but bound or embedded differently within the EXCHANGE frame.

Thus, a MOV frame, when it is part of the EXCHANGE frame, is instantiated twice.

We distinguish two ways in which one frame can be instantiated (recognized) within another:

Component fibre: The fibre is a component frame that constitutes an intrinsic part of the composite frame. This follows a specific composition path, building from “Lego blocks.” For example, the EXCHANGE frame consists of two MOV component fibres, MOV_A and MOV_B.

Overlay fibre: The fibre is not a component (part) of the frame in which it is instantiated. Instead, the overlay fibre is laid over some of the existing structure of the embedding frame. For example, the contextualized version of the TRADE frame (which is actually a fibration, as we shall see in the next section) contains several CUSTODY overlay fibres—each representing an instance of stock being held, either at the seller's custodian or at the buyer's custodian.

In many cases the difference can be ignored, so it is just being called a fibre.

Note that any construal we build is subject to further elaboration at any time—it is a (semi-)open system in this sense. In other words, we can always add constraints or remove degrees of freedom from what has been constructed so far. This openness makes the construction process adaptable to future changes—many of which result from an initial lack of information, and adding information often means introducing new constraints.

It is also possible to go in the opposite direction—by removing constraints. We will explore that further in the VFT section.

Contrast this with how programming language (PL) code is typically written using constructs like classes, objects, and functions. In the PL world, code is not open to elaboration in the same way DCM is. You have to change the code to make it more specific. You cannot have multiple interpretations of the same content— at least not without building additional abstraction layers to loosen the constraints of PL semantics, as a DCM implementation does.

Additionally, PL code cannot support arbitrary levels of reality the way DCM can—it is generally limited to runtimeand design-time levels. While there may be some stratification in the design-time domain (e.g., class inheritance hierarchies, where a superclass represents a more abstract level and a subclass a more concrete one), these levels are limited to a single identity chain, meaning that stratification is limited to "local columns".

In contrast, DCM places no constraint on the relative individuation of any two levels— enabling far more flexible and multi-layered representations of reality.

Contextualisation / Field Of View

Any element within the construal (e.g., a RELEASE fibre that represents a CUSTODIAN sending a settlement instruction to a CSD) can be traced upward to this surface level.

Thus, anything that happens within a construal can be given an answer to the question “why?” at multiple levels — one answer per level of reality — with the surface level holding the final answer.

When a TRADE frame is instantiated at the runtime level of reality, the final cause also shifts—from the TRADE level to the runtime level of reality— where, for example, the BUYER agent becomes a concrete party (a trading company that buys the stock), and the BUYER’s CUSTODIAN becomes a specific bank, etc.

Note that the “D” in DCM stands for "deep". It should now be clear what that refers to: the structures built with DCM can have many levels or layers, and the number of layers is not limited, either in count or in their relative relation or configuration. (This contrasts with programming languages, where we typically have at most single, isolated columns of class hierarchies.)

For example, in the TRADE construal, there are many levels beyond (or under) the surface level of reality represented by the TRADE frame. Below that level, we have the level of CUSTODY fibres, which themselves serve as the baseline for REQUEST_REPLY fibres (e.g., when a CUSTODIAN needs to send a settlement instruction to a CSD).

The REQUEST_REPLY frame itself contains several layers—for example, the COM level, which is composed of a MOVfibre, which in turn is composed of RELEASE and CAPTURE fibres.

Even this example shows that a DCM structure can be deeply embedded, with at least six levels of embedding for a TRADE construal.

As will be clear from the FVT section, in a more minimal FVT interpretation there will actually be many more levels (depts as the number of steps in a vantage). This is a direct consequence of the collage mode of composition.

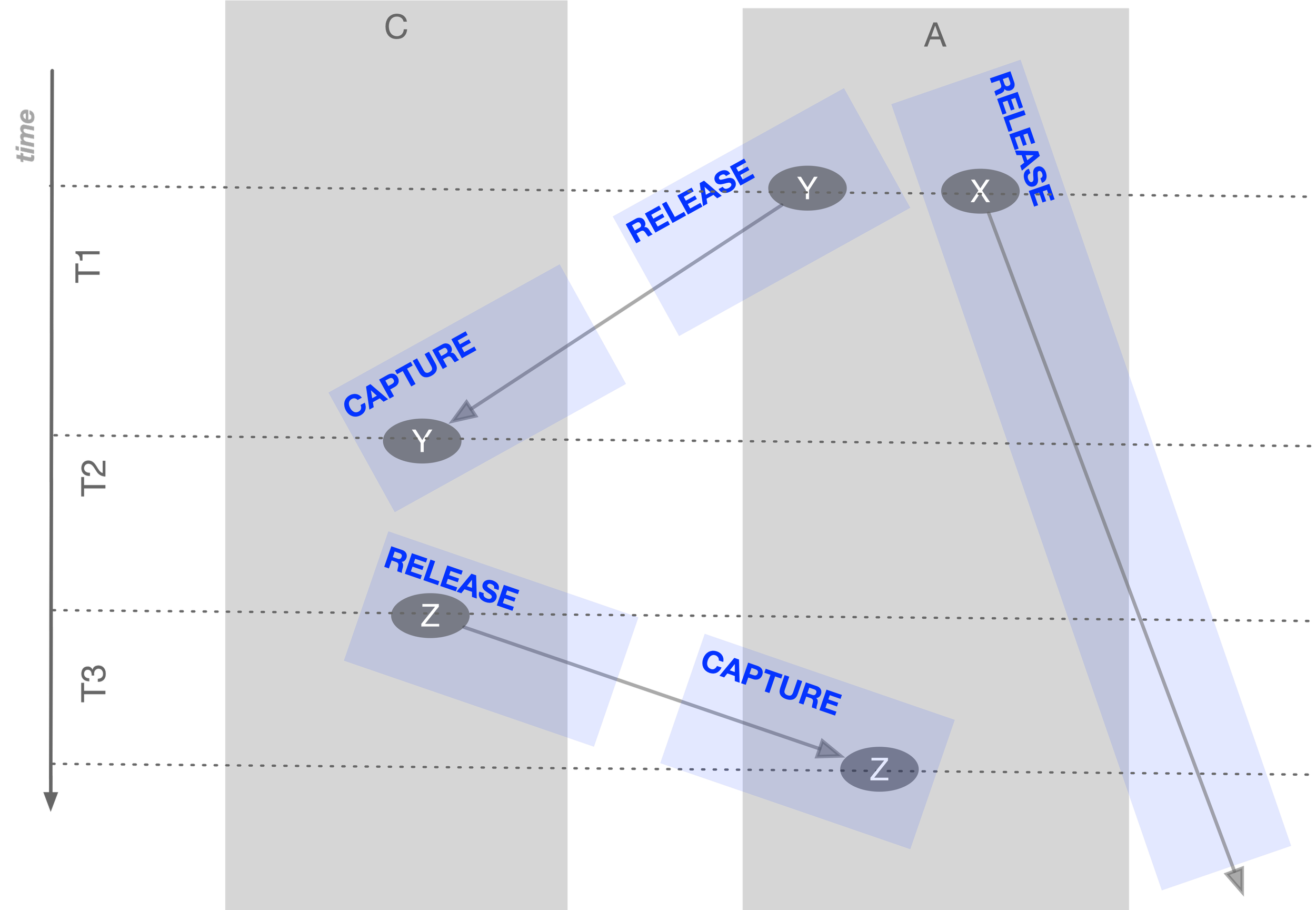

Through layering fibres, we can not only zoom into specific portions of the construed space consisting of objects and agents, (e.g., zoom into the containment of CASH by BUYER via layering a CUSTODY fibre with vostro-nostro accounting structures) but we can also zoom into time—the temporal dimension.

For instance, the REQUEST_REPLY fibre may be bound to a simple temporal interval within the TRADE construal, but the temporal structure of the REQUEST_REPLY frame is much richer: it has its own aspect, with several internal events. This refines the original interval by enriching it with its own temporal structure.

This behavior is expected if we take seriously the idea that frames can be applied freely, pivoting in any dimension, such that one fibre can elaborate (i.e., zoom into) content already framed by another fibre (or multiple fibres).

The lens metaphor also applies here: We can start with a wide-angle lens on a camera to capture the whole landscape. Then, we can switch to a telephoto lens to zoom into a single location—e.g., to focus on a single building at a distance. If we turn the camera without changing the lens, we cover more content with the same lens.

In DCM terms, this corresponds to having multiple fibres of the same frame. Just as there can be many RELEASE fibres in a TRADE construal, there can be many different snapshots taken with a single zoom lens by pointing it at different parts of the landscape.

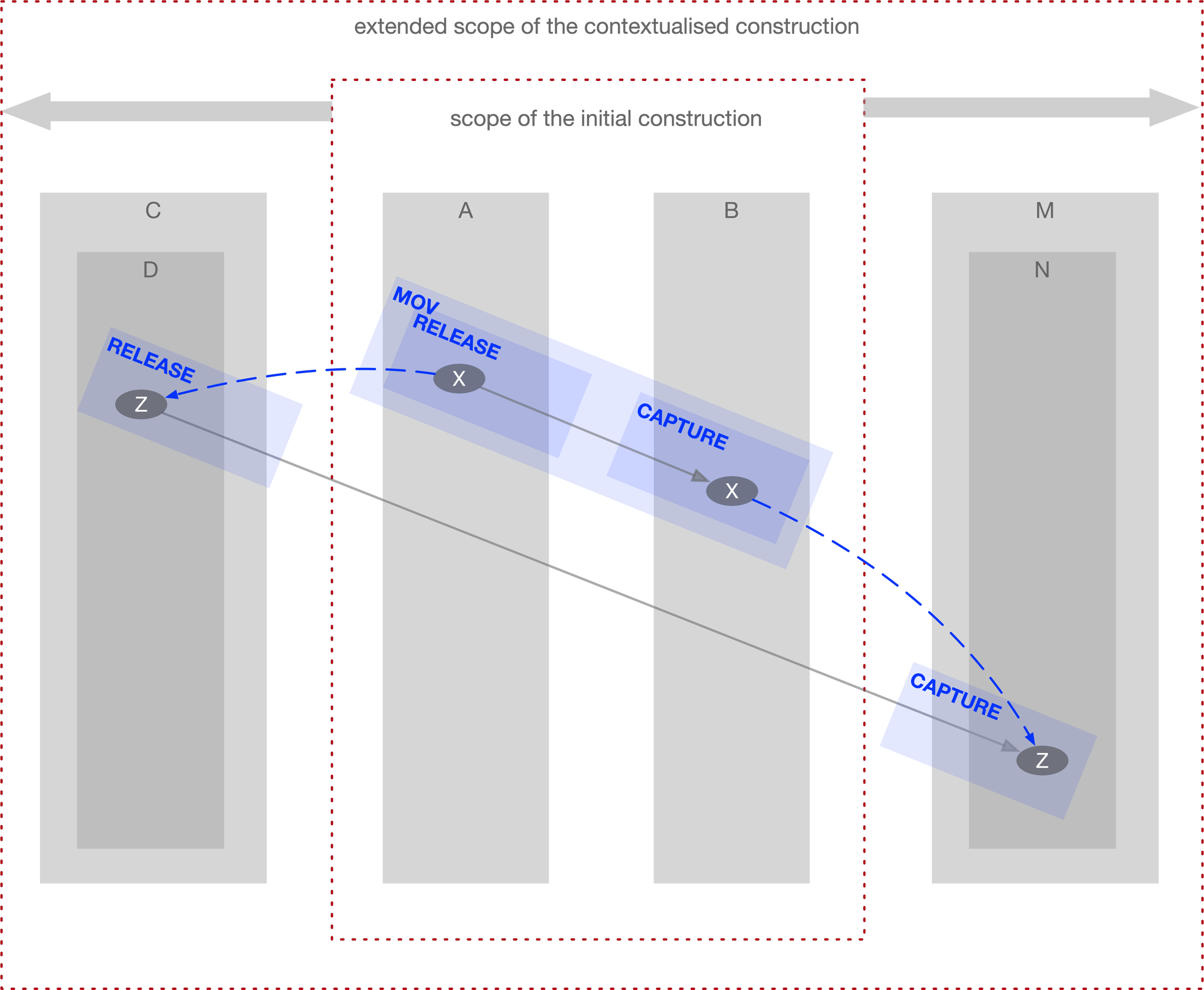

In the TRADE example, the initial construal of a trade is a TRADE frame, which itself is composed of MOV frames, and so on.

When the TRADE frame is contextualized by overlaying CUSTODY, BANK, and other fibres onto it, the construal is extended to cover more content than the stand-alone TRADE frame originally did.

It’s as if we are seeing more of the territory than before by adding additional points of view (POVs), which extend our field of view (FOV). This is the essence of contextualization. With TRADE, every overlay we add brings in additional content that was initially out of scope. Each overlay fibre contributes to expanding the area of content being covered (the FOV).

For example, the CUSTODY fibres of the TRADE frame introduce new individuals—new agents who take on the roles of CUSTODIAN for both the BUYER and SELLER agents. The scope of the content construed in this way, or the FOV of the construal, will expand as much as needed to enact the surface frame in a given context.

The reason we need to extend the scope of the TRADE construal is to enact this frame —to execute the settlement process. So, the required FOV depends on the context—on the target business process we are modeling and automating.

Note the difference between the TRADE fibration we started with and the same TRADE fibration after it has been extended to cover more content by adding overlay fibres. Informally, both have the same core, consisting of the same component fibres, and thus have the same height. In the latter case, however, that core has been extended with overlay fibres, adding to its width and capturing more target content than the core alone.

This difference can be illustrated with a loose metaphor of a tree that grows in height while its roots grow in width: the branches of the tree grow upward, adding to its height, and do not attach to the environment (corresponding to component fibres), while the roots grow sideways and downward, connecting the tree to its environment and thereby contextualising it (overlay fibres). A tree with the same branches (the same “top”) can be planted in different soil and will develop different root systems.

This way, the same TRADE frame will automatically yield different construals for settlement when placed into different contractual contexts: in one case, the trade may be CCP-cleared and involve CSDs directly, while in another it may be an SI trade involving sub-custodians. Both scenarios share exactly the same core (the TRADE frame), yet this single core results in very different construals when combined with different contractual environments that enable trade settlement.

Working at the TRADE level does not require knowing anything about how that TRADE unfolds in different environments; it provides a single access point for all cases. This “decouples” in the implementation those levels of reality that are independent (i.e. decoupled) in the target domain.