What does a PL code encode ?

How does PL code mean?

What does the code of a typical software component actually encode in order to fulfill a specific function during its execution in enterprise IT systems? How does that code produce the desired effect?

In most cases a component works not because its programming language (PL) code encodes a model of the target domain ( contains the meaning of what it is doing ). The code does not capture the entailments of the target domain to produce the desired effects (e.g., settling a trade).

Instead, the code works because of how it is situated within its immediate environment—it encodes linkages to that environment. In essence, the code represents a shortcut to a result by leveraging correlations in its immediate environment, assuming that this environment remains stable. (the specific environment is essentially encoded into the background assumptions when writing the code).

As a result, the code bypasses all the entailments and inferential structure in the target domain that generate results in the first place.

The reason a seller sends a settlement instruction to its custodian is because it wants to transfer its stock to the buyer—and because the seller does not hold the stock directly, but instead engages a third party that provides securities safekeeping services: the custodian. These are the entailments of the target domain.

Markov Blanket

There is a concept in statistics that helps describe this situation—the Markov blanket.

A software component can be thought of as being wrapped in a Markov blanket that constitutes its immediate environment. It cannot "see" beyond this blanket—beyond the specific environment into which it is embedded. That environment typically consists of other software components, each with their own encodings. The component is effectively isolated from any influence or dependency that is not part of this immediate environment, and is therefore fully dependent on it’s blanket (fully linked to it’s immediate environment).

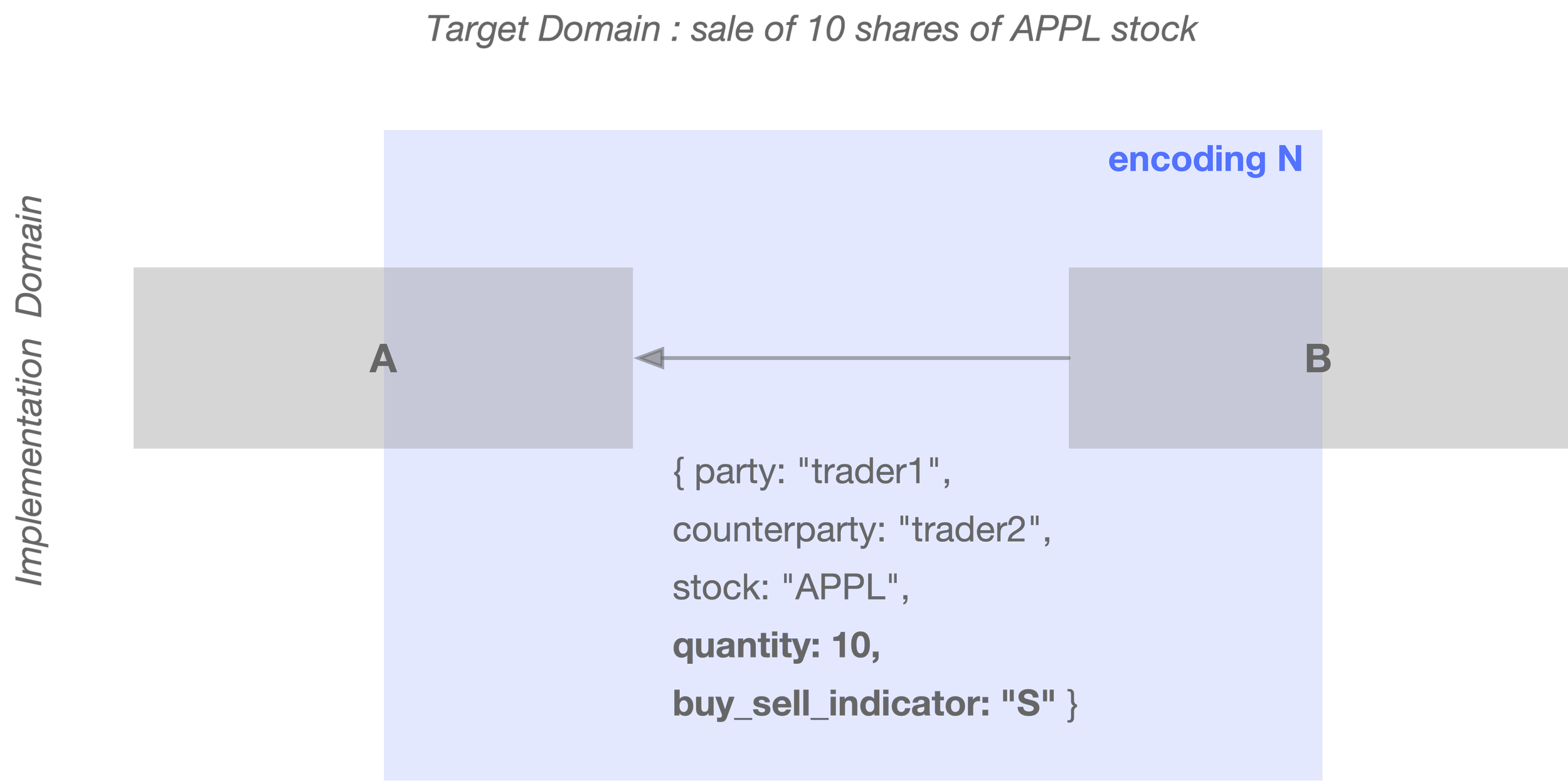

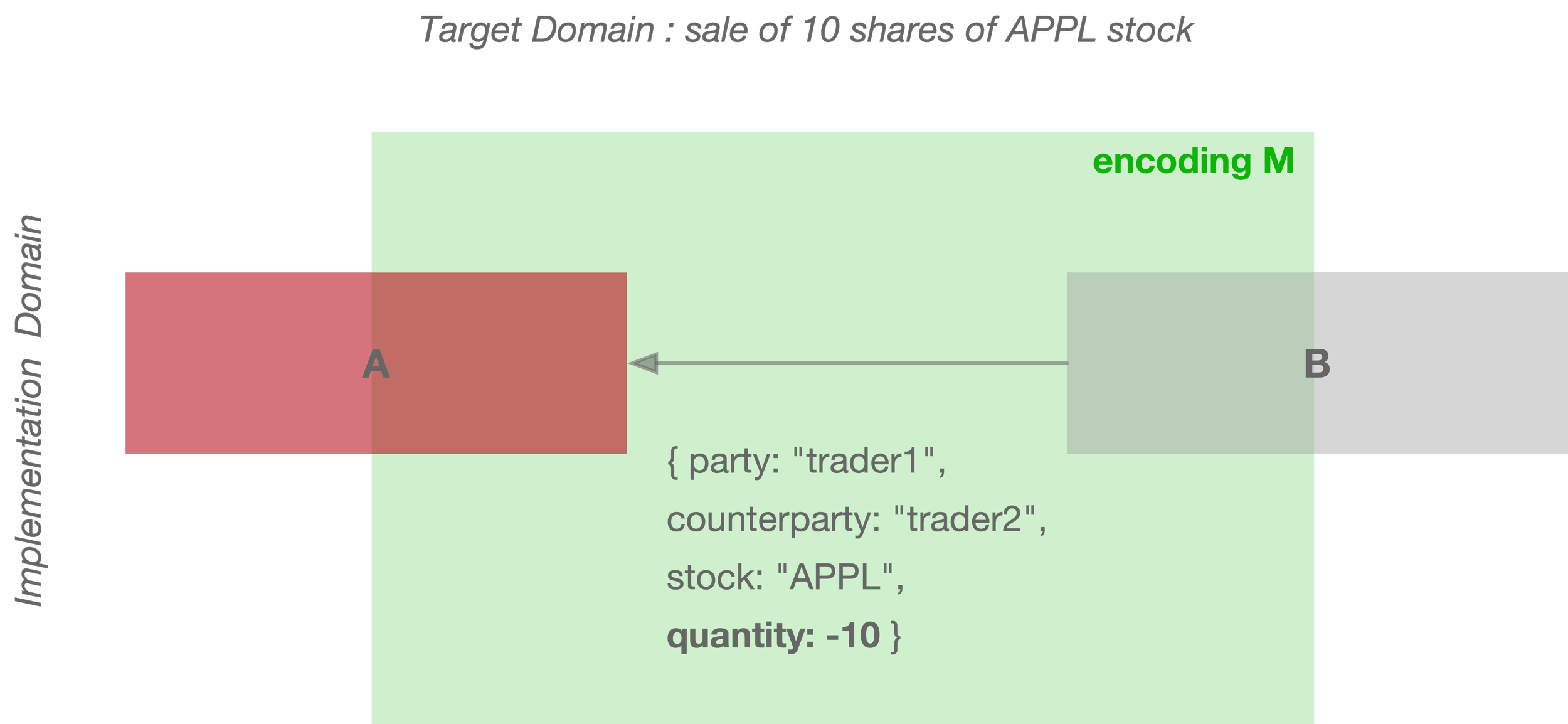

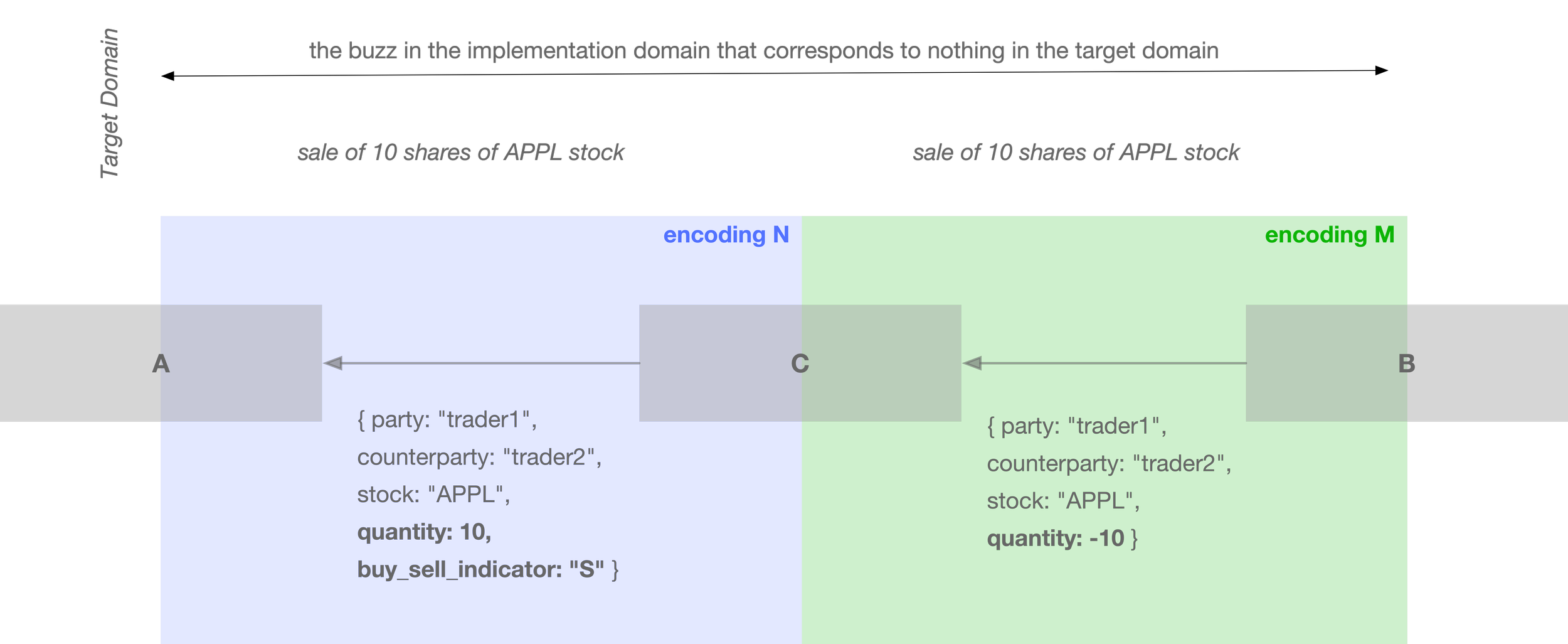

For example, suppose we have a software component A that processes a trade. It receives data from another software component B, which describes the trade. In this case, B forms part of the immediate environment of A.

Let’s say that B encodes the trade side using a key-value pair like:

{ party: "trader1", counterparty: "trader2", stock: "APPL", quantity: 10, buy_sell_indicator: "S" }

Here, "S" encodes a sell, and "B" a buy. Let’s call this environment N.

Now suppose an encoding in component B is changed and instead encodes the side of the trade using the sign of the quantity—a negative number for a sell, and positive for a buy:

{ party: "trader1", counterparty: "trader2", stock: "APPL", quantity: -10 }

The modified component B now comprises a different immediate an environment that we will call M.

The component A that is encoded to an immediate environment N will "break" when placed into an immediate environment M.

To make A work in an environment M, either A has to be re-coded, or there has to be yet another component C developed and inserted in between A and B to re-code M into N.

Importantly, all of these encodings are invisible in the target domain—they all represent the same target concept: a sale of 10 shares of APPL stock.

What changes is not the encoded, but the encoding —and that alone can break the implementation. A system composed of component A expecting N, and component B supplying M, will fail to process the trade, despite the semantics in the target domain remaining unchanged.

This situation is not unique to building software; it is also what the brain often does (according to research into cognition and perception) when taking a lightweight approach to representing the world. Instead of building rich causal models as representations of the world, an organism often relies on contingent correlations present in its environment, which are then registered and entrenched in its representations..

"The capacity of humans and other animals to perceive and to know—systematically yet fallibly to acquire accurate perceptions and true beliefs—appears to rest heavily on mere correlations in nature rather than necessities, on partial rather than full regularities. In line with this, it has been suggested that we recognize a kind of natural information—Nicholas Shea (2007) calls it “correlational information”—that is produced when there is a non-accidentally continuing correlation between one kind of state of affairs and another, such that the probability of the one kind is raised given the other (Lloyd 1989, Price 2001, Shea 2007)"

Ruth Millikan, "Beyond Concepts"

Put simply, instead of trying to figure out cause–effect chains and then separately looking for causes to predict effects, it’s often much easier to capture correlations between effects. If there is a signal S appearing in the environment every time a certain desired outcome O occurs, an organism can take a shortcut and treat S as the cause of O, even though S might merely be an environmental side effect accompanying the manifestation of the causal chain, while the actual cause C is ignored by the organism.

If we ignore causality entirely, we can’t even meaningfully refer to S as a “cause” or O as an “effect” — we’re left only with a correlation between two signals (observables) S and O. But that correlation is only reliable under specific environmental conditions — namely, those in which O appears as a side effect of the causal chain C → O. If environmental conditions change, the correlation breaks down.

And if an organism does not distinguish these changing conditions and fails to register the shift, it will continue to erroneously rely on the correlation that no longer holds, anticipating effect O upon the appearance of S, even when S is no longer linked to O (or E).

Returning to our example: Component A relies on such a shortcut, as long as its immediate environment remains N.

Within N, the correlation is stable—as long as A responds to a specific input signal with a specific output, the desired effect (e.g., a trade being processed) occurs. This happens without component A having to know why or how the result comes about.

However, if we re-code component B, thereby changing the environment from N to M, the correlation that A relies on breaks down. The "hardwired" shortcut in A now leads nowhere—attempting to jump from input to output no longer lands on the desired effect (processing a trade), but instead results in a free fall, causing the combined A + B system to malfunction.

The accidental correlations on which component A was built have changed, and A has lost its function—just as a building collapses if the structural pillars it depends on are removed.

Now note the difference between the kinds of correlations that brains rely on and the correlations that software components rely on.

The former are rooted in correlations in the physical world, which are often stable enough because they arise from the laws of physics (e.g., dark clouds correlate with wet streets).

By contrast, the latter are correlations created by the encodings of software components that constitute the immediate environment (Markov blanket). These correlations are idiosyncratic rather than universal. While such encoded correlations may remain stable if no software ever changes, in practice they can abruptly disappear when some of the components in the environment are re-coded or when the target domain itself changes.

In the example, if a single element of the immediate environment of a piece of code is re-encoded, that piece may stop functioning entirely—it breaks.

This phenomenon is typically referred to as a “bug” that requires a “fix” (i.e., re-coding component A to align with the new encoding of its immediate environment).

Note that these encodings are largely conventional and idiosyncratic, and therefore essentially random from the POV of the target domain. Neither the business nor the computer are participants in establishing these conventions. The choice of encoding thus introduces what Deleuze calls haecceity into the system — something external to both the implementation domain (software) and the target domain (business)..

The root cause of this problem lies in the necessity of encoding choice in the first place: encoding bridges two very distant domains and is inherently one-to-many.

None of the specific encodings is more fundamental than the others—they are all equivalent from POV of target or implementation. Yet, a choice still has to be made.

When such choices are made repeatedly—across different locations, by different people, and at different times—it becomes highly unlikely that the same choice will be made (the same encoding will be selected) consistently under all of these varying circumstances. This makes re-coding an inevitable artificial overhead, introducing unnecessary complexity and making software more complicated than it needs to be.

Chain Reaction Machine analogy

Exactly the same shortcut is taken by cognition when it skips the cause-and-effect network between one observable and another, and instead binds the two directly relying on a simple correlation.

An anecdotal example of this is cult cargo—where a superficial correlation between observables is detached from its context and mistaken for simple causation (believing that the presence of an object that looks like a plane should cause cargo to appear).

This kind of context-stripping and shortcut-taking avoids the need to build a model—a causal network underlying the observed phenomena. It serves as an efficient heuristic when one does not have the need or resources to build a model and wants “a quick and dirty first guess”.

In many cases, the effort required to build a model is simply not justified by the benefits of using it. Model-building is worthwhile only when the model can be fully utilized—for example, to anticipate future events, or to adapt behavior in the face of changes, especially when trial-and-error learning would be risky, costly, or too slow. (Consider, for instance, the risks and testing efforts involved after each code change in software development cycle)

The choice between building a model and memorizing a shortcut also corresponds closely to levels of comprehension. Faced with time pressure—such as during an exam—a student might skip the effort of understanding a long explanation that shows how to causally derive a result, and instead memorize the result directly, hoping that nothing changes in the ignored material (i.e., the causal path leading to the solution) by the time the exam question is asked.

None of these underlying entailments are typically encoded in a programming language (PL) component that implements a settlement system. What is encoded is the receipt of a specific dataset from one software component—requiring a particular format and content—which then triggers the sending of another dataset to a different component, with its own expected format and content, often partially copied from the original input.

This sequence says nothing about the movement of stock or the role of the custodian. In fact, the same sequence could just as easily describe a system checking the availability of an item in the inventory of an online store.

The same code can be reused across vastly different domains precisely because it does not encode their domain-specific structures.

What is actually encoded is a linkage from input code to output code: a reaction to a signal from the immediate environment (the input), and the generation of an output back into that environment—where both the input and output are semantically empty. It is up to the surrounding environment to assign interpretation to these signals or to map them into elements of a specific target domain.

People dimension

When considering a single act of encoding in isolation, being forced to make an encoding choice inevitably creates a situation in which one encoding—out of many equally valid alternatives—is treated as the encoding (i.e., the working one), while all others are effectively degraded to non-working.

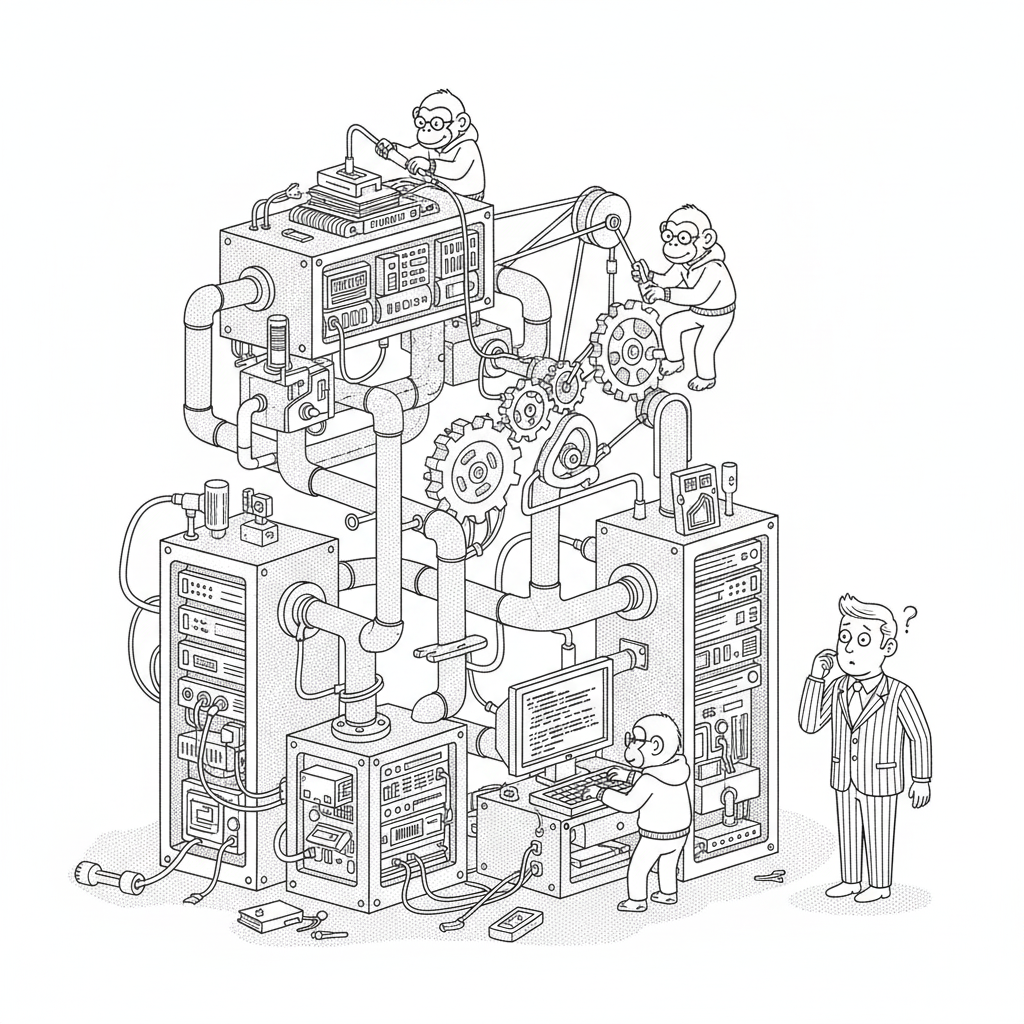

Let’s define a person whose knowledge is limited to a specific domain as an insider to that domain and an outsider to others. A prototypical example is the so-called “coding monkey,” who is an insider to the implementation domain but an outsider to the target domain. Conversely, a businessperson or analyst is typically an insider to the target domain but an outsider to the implementation domain.

To an outsider of the implementation domain, the encoding choice appears arbitrary and idiosyncratic—meaning it cannot be predicted without access to additional knowledge that does not exist within the target domain itself. That “knowledge” originates from the source that made a particular choice among many possible encodings.

As a result, making a piece of software work does not require understanding the semantics of the target domain. Instead, one must know in advance which (otherwise arbitrary) encoding decisions were made. To an outsider, this often appears as if a magician were “casting a spell” to make the software suddenly work—by altering something that seems irrelevant or invisible from the perspective of the target domain (e.g. "fixing a bug").

At the same time, a coder may have no knowledge of the target domain at all (i.e., the “coding monkey”)—meaning they may not understand what the software is actually about.

In such cases, the coder doesn’t need to understand the target domain, as long as they possess the “secret knowledge” of the encodings themselves. As long as the coder knows which encoding choices are correct, they don’t need to understand what the code actually encodes in order for it to produce the desired effect in the target domain.

As a result, functioning software may appear almost magical to individuals confined to their respective domains. Consider, for example, a scenario where executing a set of programming language instructions—altering memory values and sending a datagram over the network—somehow causes a stock to change ownership.

To the coder, who lacks understanding of the target domain’s entailments: “I just know which button to press, and the effect happens—like magic.”

To the business analyst, who doesn't understand the inner workings of code: “I know what needs to happen, but I have no idea what ‘spell’ to cast to make it so.”

In both cases, the actual causal chain remains opaque—hidden beneath layers of arbitrary encodings that must be memorized or preserved rather than understood.

The cost of this ignorance is substantial: systems built in this way do not scale effectively, become highly fragile (a single re-encoding can break the entire system), and often devolve into opaque black boxes. In essence, when they do function, it is more by frozen accident than by design.

Navigating a labyrinth of dispositional encodings

How large is the labyrinth? How long is the path? How can someone who didn’t build it possibly know the answers?

This is also why it's nearly impossible for an outsider to produce accurate estimates when implementing a change to a software system.

How could one know how long it will take to traverse the labyrinth and dig a new tunnel connecting one part to another—just to enable a new feature or modification in the target domain?

Furthermore, insiders in each domain are often discouraged from learning about the other. For a business expert, learning to navigate the implementation labyrinth—even if they are as technically savvy as the coders—may not be worth the effort. Each labyrinth is unique, shaped by idiosyncratic encoding choices, so the knowledge gained may not transfer. The next software system built for the very same domain is likely to present an entirely different labyrinth, requiring the path to be rediscovered from scratch.

For a coder, gaining deep understanding of the target domain—even if they possess the some business expertise—can seem unnecessary or impractical. This is because the software doesn’t model the domain itself; it functions through its placement within a technical environment that obscures business meaning behind layers of encoding. To implement a feature, the coder doesn’t even need to understand the full labyrinth—only a small part of it where a new branch has to be added.

Having to make encoding choices repeatedly when building software is analogous to navigating a branching labyrinth—where only one specific path leads to a functioning system.

A person who possesses knowledge of this correct path is like Ariadne, the mythological guide who helped Theseus escape the labyrinth.

Because of this, any change to the system must “follow the thread”, the path, meaning that instead of focusing on the actual nature of the change in the target domain, most of the effort is spent discovering and following these paths—and extending them to accommodate the new change.

As software grows in size and complexity, these paths become deeper, develop additional branches, and accumulate layers of noise introduced by implementation domain alone. Navigating the encoding labyrinth—following paths that are unpredictable from the outside—makes the implementation opaque and non-transparent: a black box.

These encoding labyrinths obscure the structure of the target domain. For outsiders to the implementation, there is no direct access to target domain meaning.

To reach something meaningful—an element of the target domain—one must know or rediscover the path through the labyrinth. This process imposes a significant cognitive load and consumes time, with the scale of this overhead being unpredictable from the outside.

Correlations as shortcuts

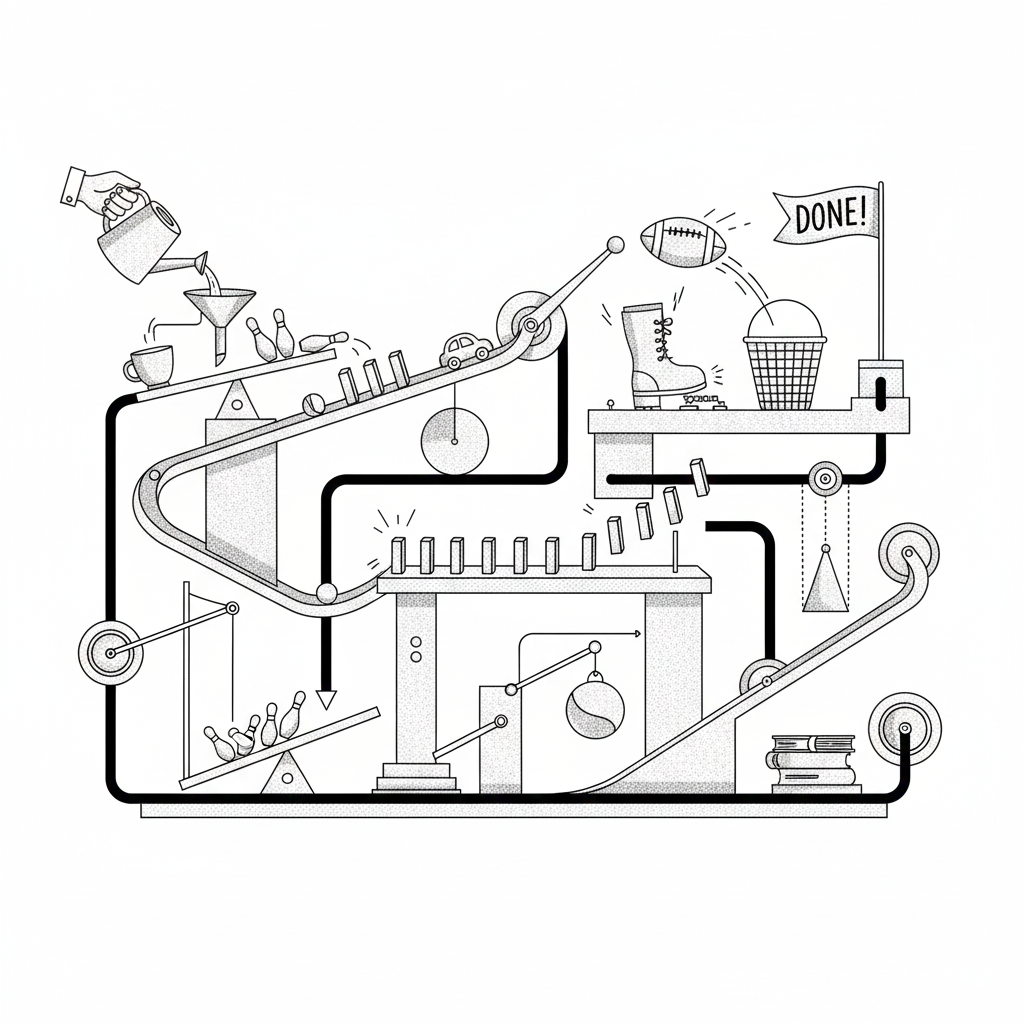

A chain reaction machine is a good visual analogy for how typical PL code works: it does not encode the structure of the target domain, whether causal or topological. Instead, it encodes reactions to the encodings of its immediate environment.

These encodings are not treated by a software component as representations of something in the target domain but are taken at face value—just as when an apple in a painting is mistaken for an actual apple, with the brushstrokes attributed to the fruit rather than its depiction.

It is only the human coder who possesses the link between those strokes of code and memory cells and something in the target domain (such as a trade), and who can decode them back — for whom the code represents something beyond mere characters and numbers. The programming language itself, however, lacks this link and can only process characters and numbers within its syntactic and hardware constraints — much like a link in a chain reaction machine that simply connects the preceding and following nodes without any understanding of the final outcome.

The encodings of a software component’s environment, which together form its Markov blanket, allow the component to shortcut directly to reacting to specific input by producing its own specific output, which is then passed to other components downstream in the reaction chain.

So why be forced to make a choice that doesn't need to be made?

The approach taken by DCM is to avoid building the labyrinth in the first place—to minimize the distance between domains and to make encodings as simple as possible, ideally one-to-one (isomorphic). It eliminates arbitrary encoding decisions by ensuring that the implementation domain closely mirrors the target domain—in other words, by making the implementation a model of the target domain.

The trade-off is that the target domain must be formalized, i.e. expressed as a formal system, which has to be executable (eventually via the very same layer of programming language implementation).

Simply encoding the target domain directly in a programming language—or using low-code tools or frameworks—will not be effective, as the preceding discussion has demonstrated.

Once a modeling relation is established between the target and implementation domains, one can directly express the desired feature or change in target-domain terms—without having to supplement target domain knowledge with the extensive, often disposable knowledge required to navigate the encoding labyrinth.

Suddenly, the implementation becomes transparent—revealing its structure and logic—which in turn opens up new possibilities for changing or extending the system, possibilities that were previously prohibitively complex or completely inaccessible.