Relation is not a Thing

Evolution didn’t give us minds to mirror the world objectively, but to act within it in pursuit of our goals. An objective view of the world is, at best, a byproduct.

The strength of the mind lies in its ability to bend the world to fit the needs of the cognizer through an extensive repertoire of perceptual and cognitive operations. The larger the brain of an organism, the more it can afford to detach from what is immediately given in its perceptions of the here and now.

At the same time, evolution has pressured the mind to conserve resources and minimize risk. Holding onto information is costly—not only in energy, but also in interference. Thus, the natural tendency of the mind is to reduce and simplify. Forgetting, in this sense, is not a flaw but a feature.

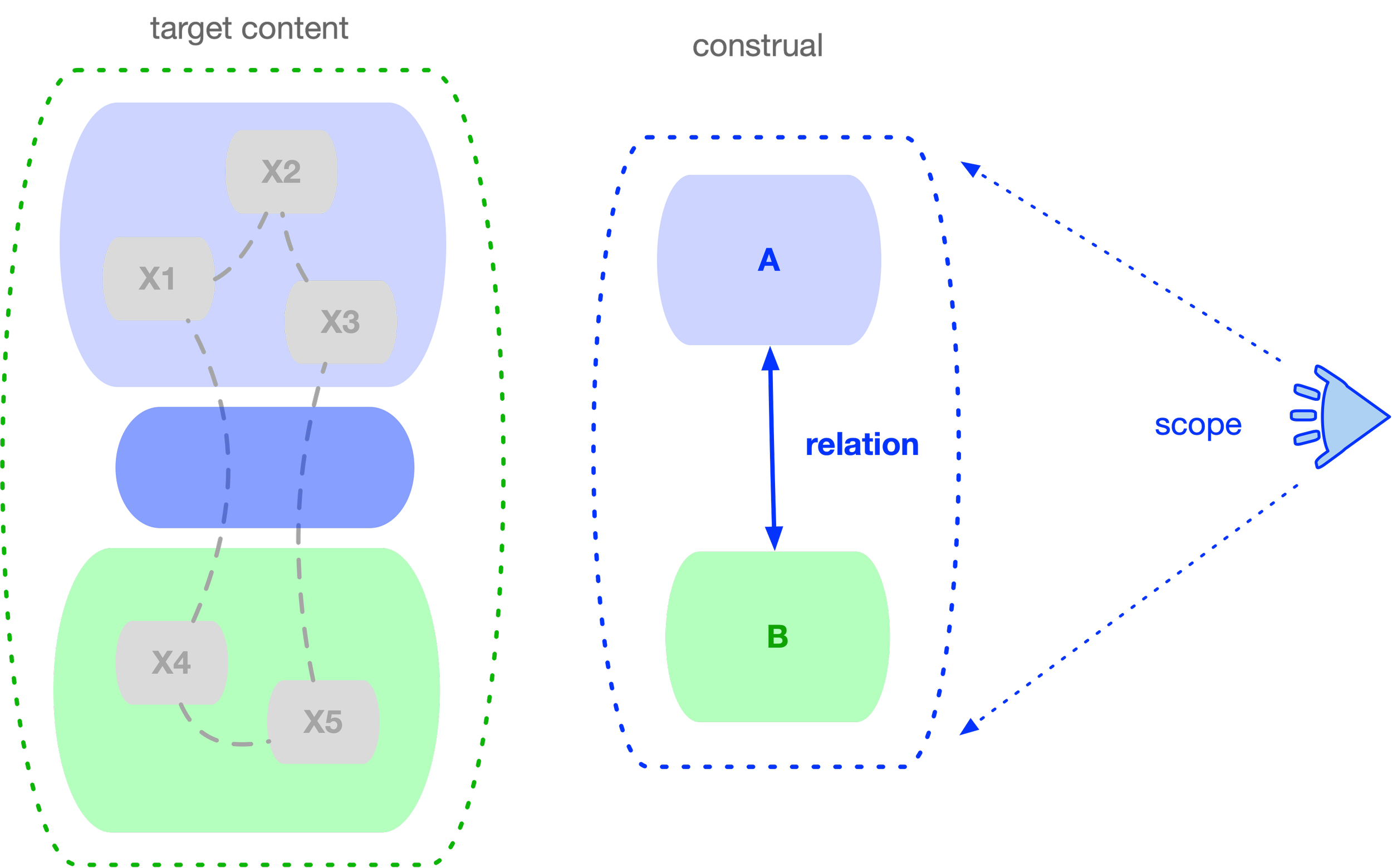

Attention depends on managing the scope of the content being cognized—much like the field of view in a camera. Bringing something into scope pushes other things out.

Language often relies on these detachment and scoping mechanisms. They are what make the world graspable at a human scale.

One common operation is reduction of scope of the content (the narrowing field of view) while simultaneously replacing identity of the complex construction with identity of one of its parts. A part now stands for the whole —a case of metonymy in linguistics.

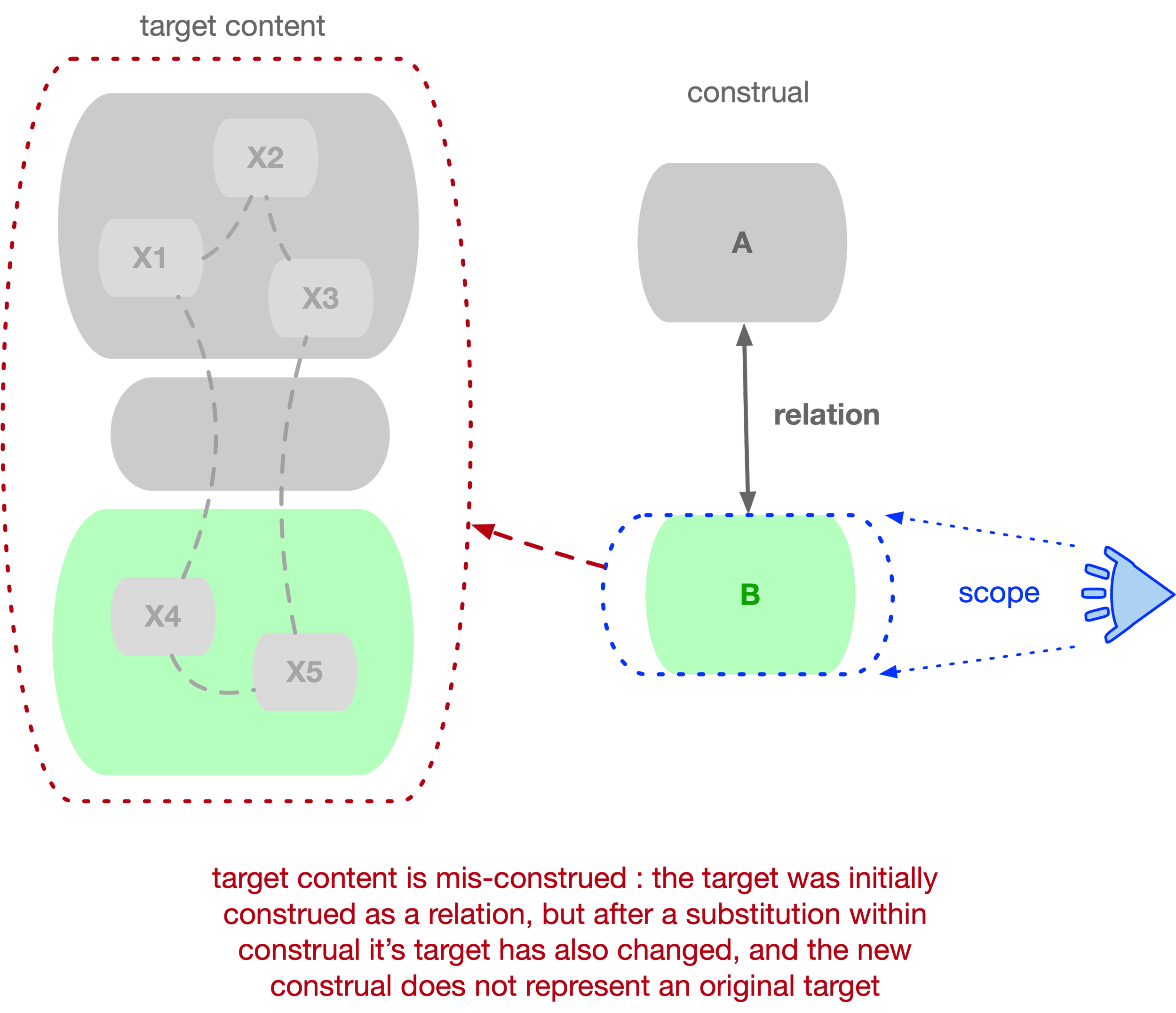

But the flexibility of these mechanisms comes with the risk of misconstruing the world: sometimes the mind detaches and then oversimplifies in the wrong way, losing critical information about the subject matter.

One example is replacing a relation with a thing—usually by substituting the relation with one of its participants.

Objects are easier to hold in mind than relations: an object is one unit, while a relation requires individuating three (two participants plus their link). Whether each unit corresponds to a dedicated neural assembly that is then bound together temporally, or whether the brain implements this in another way, is not of particular importance here.

When such a substitution happens, a construct that originally referred to a relation loses its initial meaning. Yet the mind may not detect the substitution and may continue to rely on the construction as if it still carried its original meaning.

Below, we will argue that this tendency to substitute a relation with one of its objects underlies many dogmas in software development.

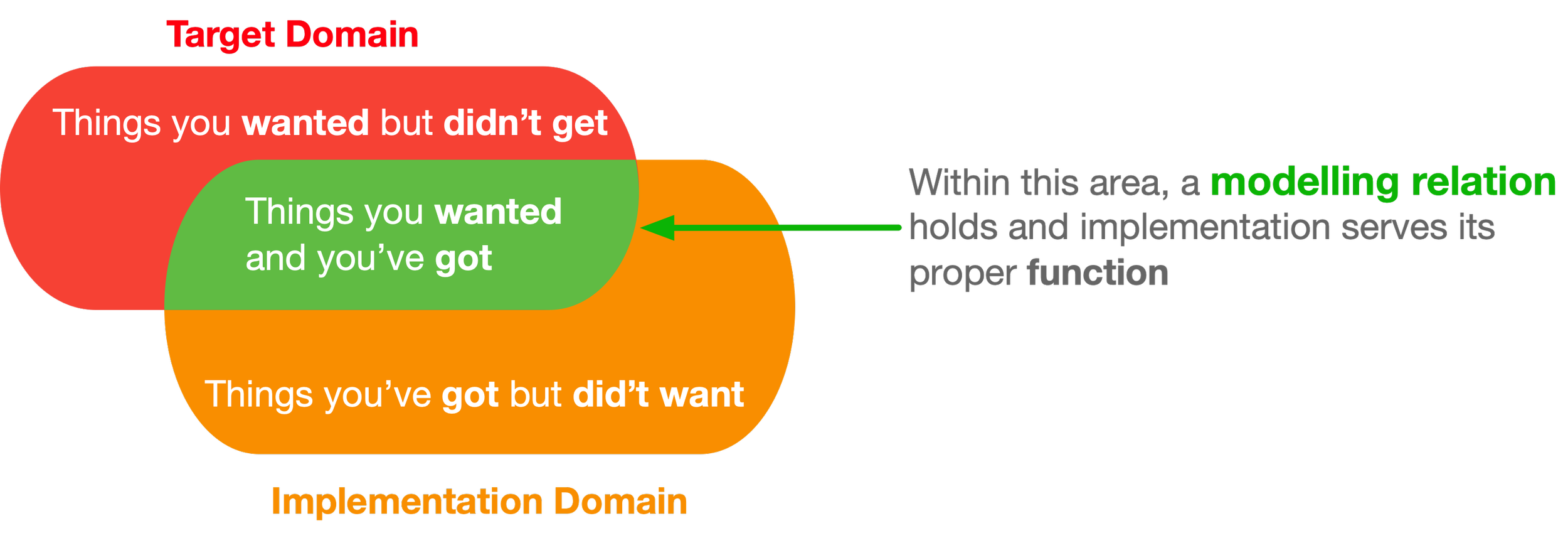

With the modeling relation out of sight, an implementation may lose its proper function, and all the usual problems in software development arise, as noted elsewhere on this site: some structure inherent to the target domain may be lost, while additional structure inherent to the implementation domain may be imposed onto the solution.

Relations mistaken for Things

Examples in Software Development

Coding

The process of software development is often referred to as coding (writing code in a programming language).

A substantial portion of this site is dedicated to arguing that writing code is not an independent activity—it always serves a purpose.

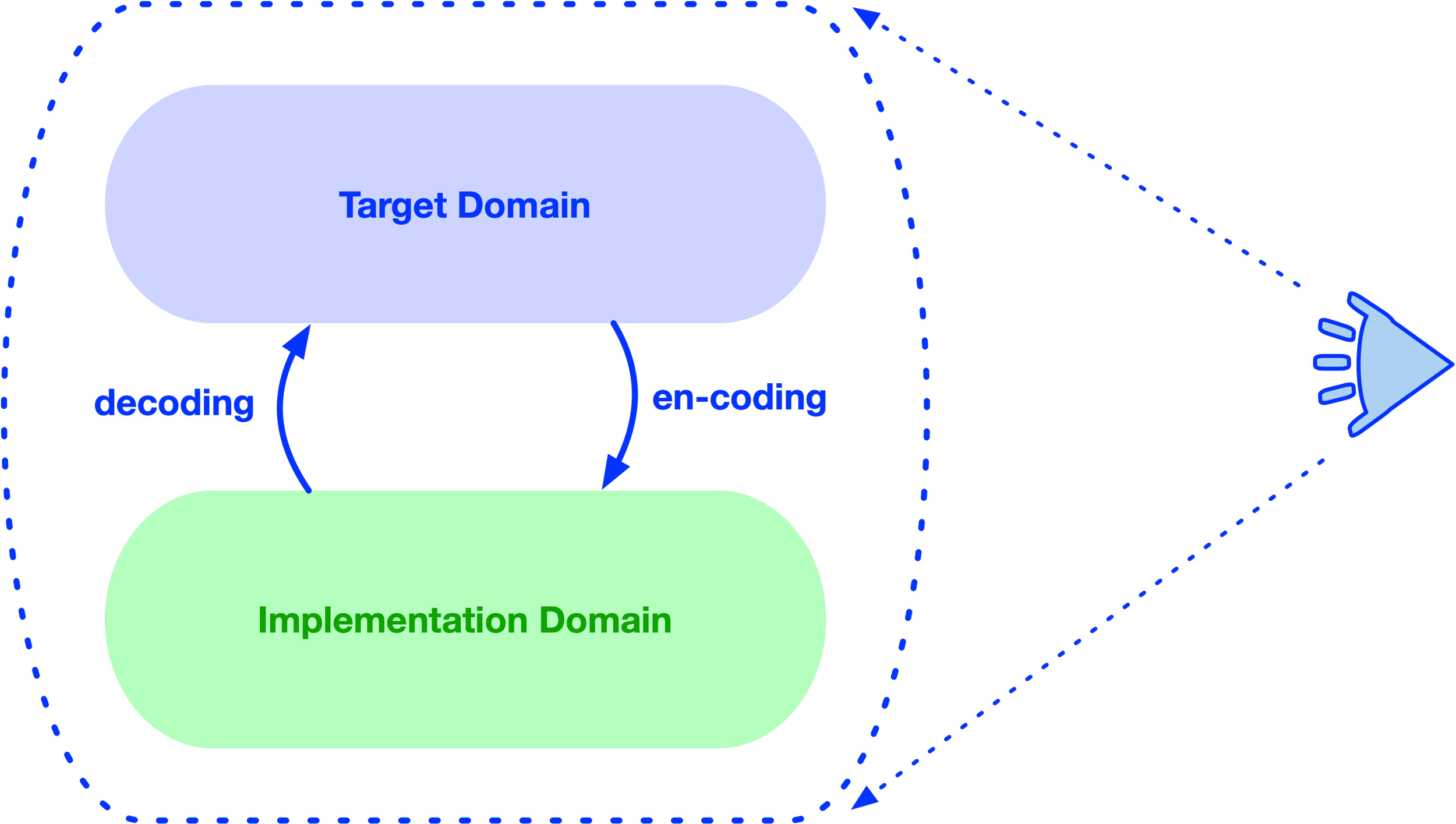

The code being written constitutes an implementation of some target domain.

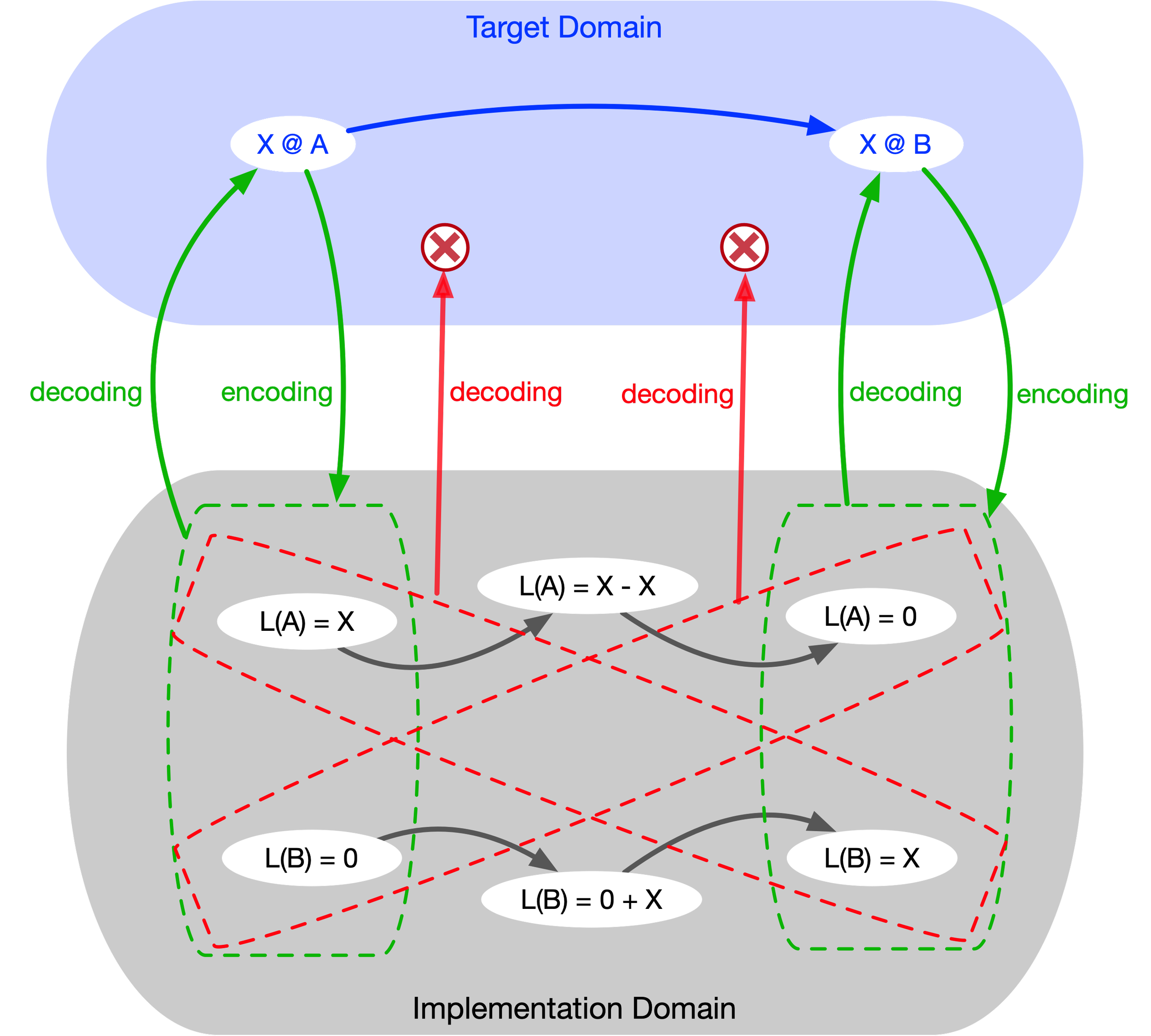

If the code serves its function perfectly, there will be a modeling relation established between the software system and the target domain. The (relevant part of) target domain is thus encoded into the implementation domain. Conversely, when we look at elements of the implementation domain, their meaning is revealed by decoding them back into the target domain.

Hence, the process of writing code is more accurately construed as a relation between elements of the implementation domain and those of the target domain.

Strictly speaking, it should be called en-coding rather than just coding.

What is often called reverse engineering is simply following the same encoding relation, but in the opposite direction—a decoding.

Coupling / Decoupling

One of the most widespread dogmas in software development states that coupling is bad and decoupling (or loose coupling) is good.

But the term coupling denotes a relation, not a thing. Without being explicit about the participants in that relation, the term is meaningless.

Coupling can also be presented as a matter of degree—it can be tight or loose. This spectrum is then projected onto the normative scale of bad-to-good.

By now, a reader may notice that the modeling relation discussed on this site is at the core of what is actually going on here. Consider the “things you’ve got but didn’t want”—the additional constraints that exist in the implementation domain but not in the target domain. If we restrict our view to this side of the modelling relation, we get the “loose coupling is better” story.

This area resulting from domain intersection, represents the noise of implementation—unwanted constraints imposed on the target domain—which should be minimized. It is in this sense, that the statement “loose coupling is better” has a legitimate meaning.

But that is only one pole of the relation.

On the other side of the domain intersection diagram, we have the “things you wanted but didn’t get”—constraints of the target domain that are missing (lost in translation) in the implementation domain.

The most foundational example is the absence of space-time topology in computers, which leads to the loss of the notion of a continuous trajectory of an object.

In the real world, an object moving from place A to place B cannot be in two places at the same time, nor can it be nowhere. But in programming languages, where there is no space-time—only independent memory cells with stored values—that constraint is absent.

Thus, a PL implementation of a financial transaction decouples credits from debits by breaking space-time topology - decoupling “being in place A” from “being in place B”.

Compensating for this decoupling by "glueing broken pieces back together" comes at a huge cost—in software complexity, potential errors, and the sheer time and effort required for implementation.

This kind of decoupling is an example of the implementation domain losing constraints inherent in the target domain—i.e., loss of information during encoding.

Obviously, from this perspective, tight coupling becomes synonymous with “good” and loose coupling with “bad.”

Another rather extreme example is the powerful “decoupling device” invented during the French Revolution—the guillotine. For some reason, nature decided it was a good idea to couple one’s head to one’s torso. The guillotine was designed to rectify that situation though bearing some side-effects.

To sum up: imputing “good” or “bad” to coupling makes no sense unless we’re clear about which relation is under discussion. As this case suggests, software development theory often oversimplifies things—throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

Microservices / Monolith

A related dogma is “microservices everything”—where breaking down an implementation into smaller, technically independent pieces is taken as good practice, while larger software pieces are labeled a monolith and dismissed as bad. This is an example of an artificially introduced Humpty Dumpty problem, analyzed elsewhere on this site.

At this point, the reader may already see that this is just another case of the same misunderstanding of coupling.

The question of size, in itself, is meaningless when taken out of context. Is small always good and big always bad?

Normative evaluation is always the result of measurement, and it always depends on context.

What is more concerning is that the size question is often posed as if it were a purely technical design choice. But as the modeling relation makes clear: the implementation should try to match the target domain in its degrees of freedom or constraints. Any deviation in either direction is an implementation defect.

From this perspective, the size of things in the implementation domain should be a function of the size of things in the target domain.

So, if there is a constraint (a coupling, in the sense of the previous section) in the target domain, it should be present—or, if necessary, reproduced artificially—in the implementation domain.

Hence, what is micro or macro is not a free parameter subject to the developer’s methodology or preference. That parameter is already fixed in the target domain. The implementation’s job is simply to align with it as much as possible.

In other words, the “size of services” is not a decision to be made at the level of implementation; it is determined by the target domain. The job of the implementation is to identify the latter and link to it.

Similarly, “the number of microservices“ is a meaningless parameter in itself. If a service does something meaningful, it must originate from the target domain, where the individuation of services has already been made prior to implementation. The implementation should attempt to minimize any deviation from that individuation.

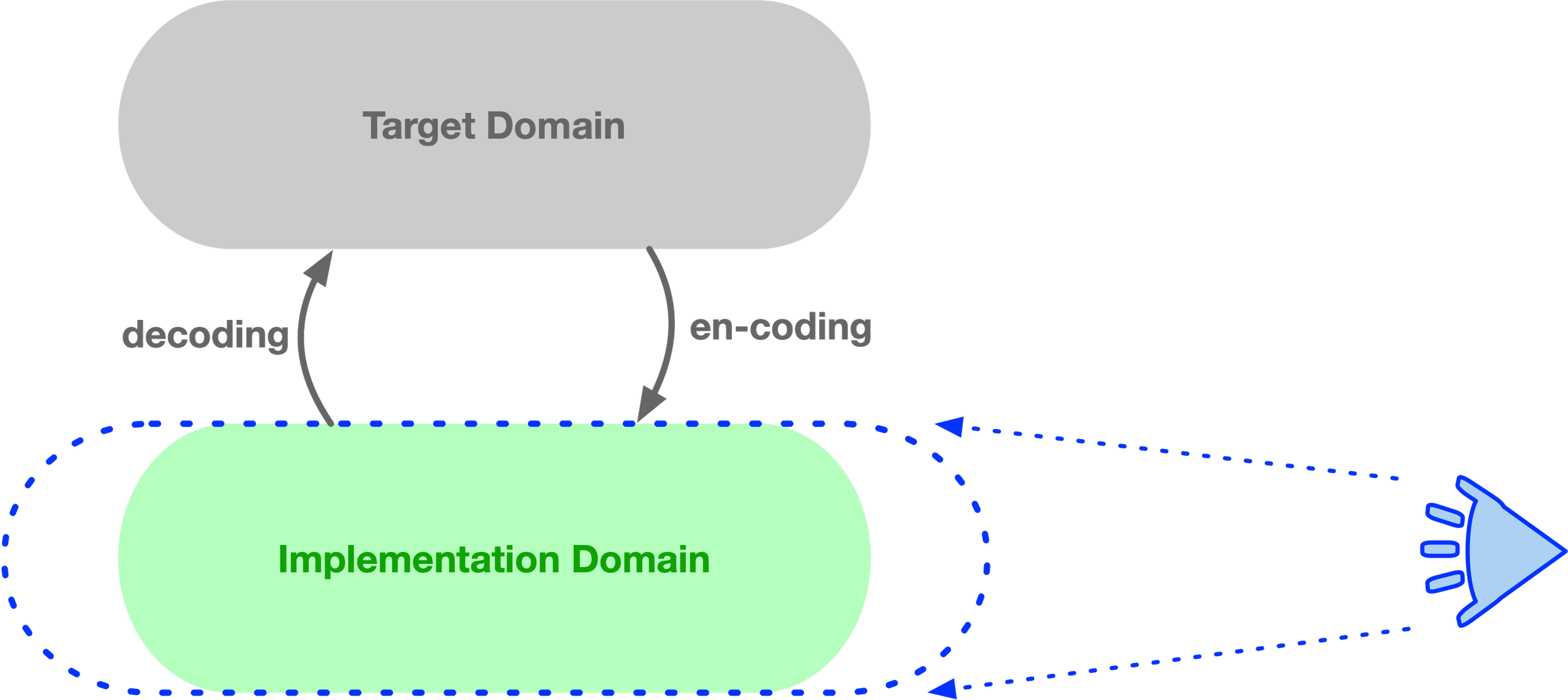

If all we are focused on is just the implementation domain forgetting its relation to the target domain, we risk loosing modelling relation.

The implementation domain can now forget the structure of the target domain—it loses information and presents only a part of the target as if it were all there is.