Defining a Trade and implementing it’s settlement

in just a few pages of DCM code

This section shows how a trade settlement process can be implemented in software by specifying only a minimal amount of meaningful information about it.

By means of DCM, we are essentially formalizing a fragment of the target domain of trade processing — constructing an executable model of it (a DCM implementation that stands in a modeling relation to that fragment of the target domain).

With just a few pages of DCM code — which can also be presented through diagrams — the entire settlement process involving multiple parties can be orchestrated in a distributed manner without writing a single line of traditional PL code.

None of the traditional artifacts of software development — such as services, messaging, databases, or APIs — need to figure in the solution; they are essentially at the wrong level of description when dealing with the automation of the business process itself.

The settlement example presented here is a simplified version of a real trade processing and may differ in some details—or lack thereof—from the specific trades handled in various trade processing systems. For instance, we do not include a CCP in the settlement process here.

Nevertheless, the main point of this example is to demonstrate that the approach scales well to real-world levels of complexity.

Trying to capture every detail of a specific trade processing system would only make the example unnecessarily long and complex.

Note that this version of the DCM language is a prototype and therefore contains a number of idiosyncrasies that will be eliminated in later versions. This, however, does not undermine the main argument of this demo: it demonstrates the inferential power of a formal conceptual description of the business domain, making traditional methods of coding (for this domain) directly in programming languages redundant and highly inefficient.

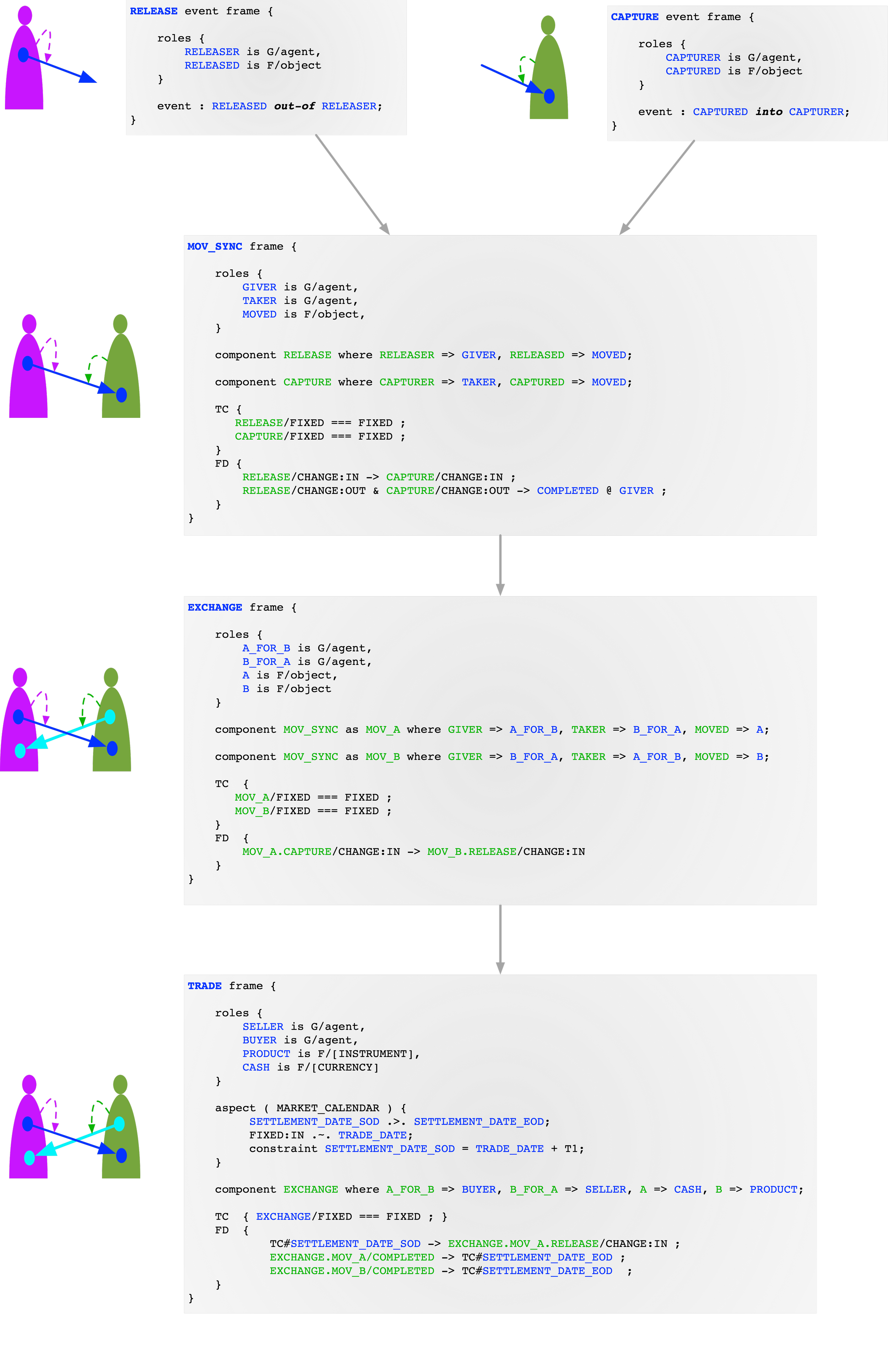

Building a TRADE through composition

A TRADE is a composite frame - a schematic structure made out of elaboration of even more schematic ones.

Here, we present a specific composition path, justified not only by existing models of construal (in cognitive linguistics) but also by the general morphology of perception.

This composition path (having a structure of a tree) has 4 levels and is displayed on the left.

The first level of the composition path consists of the RELEASE and CAPTURE frames. RELEASE represents a figure leaving an agent’s dominion, while CAPTURE represents a figure entering it.

These are irreducible primes. Even at this most basic level, the building blocks already carry figure–ground construal, along with dynamics, causal structure, and temporal structure—intrinsic dimensions of any frame.

The second layer in the hierarchy is the MOV_SYNC frame, representing a movement. It is the first frame analyzed into components—RELEASE and CAPTURE—but it cannot be reduced to them alone. What defines MOV_SYNC is the linkage between their dynamics: the start of RELEASE triggers the start of CAPTURE.

Furthermore, there is a point where the GIVER ‘knows’ that not only has the RELEASE action been completed, but the CAPTURE action has been completed as well (that is why it is called MOV_SYNC and not just MOV).

Note the binding that the MOV_SYNC frame imposes on its component frames: the agent acting as GIVER in MOV_SYNC is the same agent acting as RELEASER in RELEASE At this level, we already begin to observe a superposition of two POVs—a collage model of building large constructs from smaller ones.

The third level in the composition hierarchy is the EXCHANGE frame.

It is composed of two instances of the MOV_SYNC frame from the previous level. While both share the same underlying structure, they are bound to different elements within the composite frame—overlapping in some content while diverging in others. The EXCHANGE frame thus arises by “copying and twisting” MOV_SYNC.

Note that we can choose to skip this level altogether and compose TRADE directly out of MOV fibres. In this case, the MOV fibres will be equally accessible in either construction, and the user does not need to worry about the specific compositional hierarchy being employed. In this sense, the compositional hierarchy is transparent.

The fourth level is where we define the TRADE frame.

A TRADE frame is analyzed into a single component — the EXCHANGE frame.

Thus, the TRADE frame is a direct elaboration of the EXCHANGE frame.

It elaborates two figures into an INSTRUMENT and CASH.

The TRADE frame adds additional temporal coordinates corresponding to the start of the trading day and the end (closing) of the trading day.

It also introduces an additional causal structure: the release of cash is triggered at the start of the settlement date, and the movement of both cash and stock is expected to be completed by the end of the settlement date.

The next step is to contextualize the TRADE frame in order to make its settlement possible.

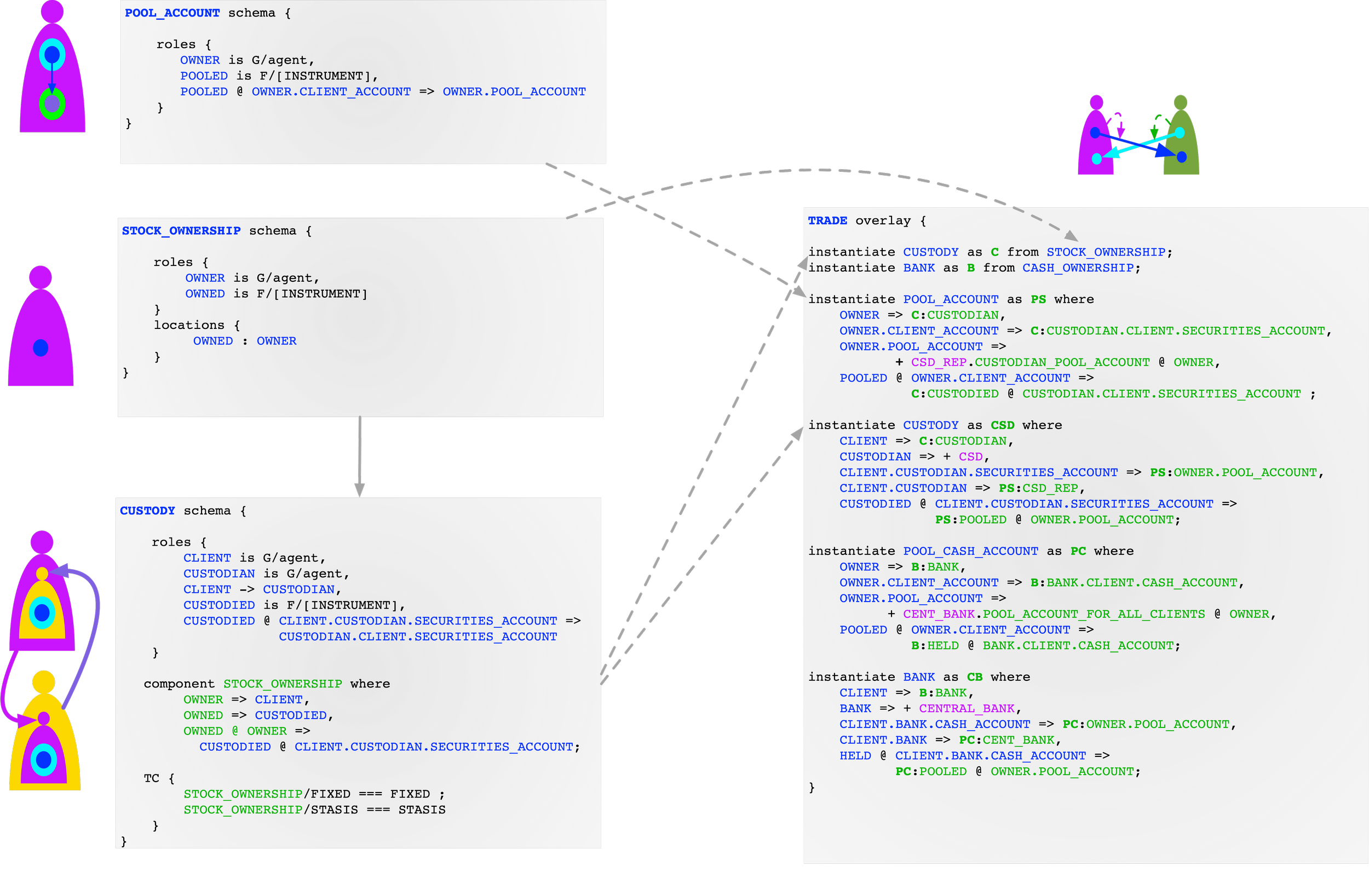

The fact of owning a stock can be represented by a STOCK_OWNERSHIP frame, whose semantics are: a figure of type INSTRUMENT (called OWNED) is located within the dominion of some agent (called OWNER). However, the instrument is not directly held by the parties involved in the trade. Instead, each party employs the services of an additional party to hold the instrument on their behalf.

Here, we are focusing on the instrument dimension, but a similar construal applies to the cash dimension.

This arrangement is represented by another frame — CUSTODY — which models a contract between two parties: one playing the role of CUSTODIAN, the other the CLIENT.

The arrow from the STOCK_OWNERSHIP frame to the CUSTODY frame represents the fact that the former is a component of the latter.

This makes the CUSTODY frame an elaboration of the STOCK_OWNERSHIP frame.

This relationship is exploited when we use these frames to add additional contextual structure to the TRADE frame defined earlier - to extend the scope of TRADE construal to cover content which is required for settlement of the trade (extending the Field of View of the TRADE construal).

The way an elaboration is created from a baseline is topology-preserving: what the baseline specifies (i.e., the stock figure being within the dominion of its owner) remains true in the elaboration.

The stock is still within the dominion of an owner — only the structure of the dominion itself is elaborated.

The ability to create topology-preserving elaborations enables “structural multiplication” — a concept analogous to a semi-direct product in abstract algebra — allowing us to describe independent aspects of reality separately (thus preserving human-scale descriptions), while still being able to compose these aspects into a single and coherent reality (along dimensions where they minimally overlap, i.e. respecting how one component of a product is linked to another).

We can write something akin to a mathematical formula for a TRADE using this ‘structural multiplication.’ This illustrates the concept of a generating kernel, on which DCM is based: a DCM model captures semantic and causal relationships between its components, allowing a small description to generate a large configuration—like a tree growing from a small seed, or a 3D shape generated by its geometrical formula.

Building Context required for Settlement

Now, we can apply the elaboration of STOCK_OWNERSHIP into CUSTODY to the TRADE frame — meaning that any instance of the STOCK_OWNERSHIP frame (as a pattern) found in the TRADE frame can be elaborated into an instance of the CUSTODY frame.

The STOCK_OWNERSHIP frame can be captured within the TRADE frame just as a pattern in being detected and captured in a target structure. For each captured (STOCK_OWNERSHIP) instance, we aim to instantiate its elaboration (CUSTODY) at the same level of reality as it’s baseline. Thus, the CUSTODY frame must be instantiated within the TRADE frame’s level of reality.

At this point, we have a choice regarding how to ground the additional structure in the CUSTODY frame — structure that is absent in the STOCK_OWNERSHIP frame acting as a baseline.

If we provide no additional constraints, the only constraints that apply will be those defined by the elaboration relation itself — e.g., the fact that the CUSTODIAN agent is individuated by the CLIENT, introducing a functional dependency of the CUSTODIAN's identity on that of its CLIENT.

This is how the CUSTODY frame is instantiated in the TRADE frame for the first time (the first line code below) — as an overlay fibre — a fibre that is laid over an existing construal just like in a collage.

When the CUSTODY frame is instantiated a second time, there are additional constraints specified on how to bind it’s elements - by binding into an already existing elements or individuating new element (the ‘+’ sign).

Each instantiation statement in the TRADE overlay code (on the right of the picture below) adds a fibre to the TRADE construal.

However, these fibres are not components of TRADE in the same sense as EXCHANGE is.

Rather, they are laid over an already existing structure — much like layers in a collage.

We have now built a construal that is sufficient to execute the settlement of a trade at the conceptual level. The part relating to the cash side is not shown here, as it is similar to the instrument side.

At this point, individuals (e.g. business analysts) concerned purely with the business domain can step away from the process, as the formalization of the TRADE example for that domain has been completed.

However, this construal is not sufficient to execute a settlement at a more concrete level — that is, to run it across distributed software systems involving multiple parties to the contract.

Continuing elaboration of a TRADE construal at the technical level

This additional implementation layer — for which what we have built so far serves as a model — will be discussed separately, as it requires its own (theoretical) treatment beyond the scope of this example.

This layer consists of overlaying instances of frames that implement communication between agents: instances of COM (communication), and REQUEST_REPLY (which includes COM as a component). The COM frame itself consists of RELEASE and CAPTURE component frames (which involve a specific kind of figure).

In this way, the same mechanisms are used consistently all the way down when building with DCM — layering new fibres over the TRADE construal we have built so far, like adding flesh onto bone.

Feeding DCM code into compiler

Given that we have elaborated the TRADE construal to a level specific enough to be executed by software, we can now feed all the DCM code we have written into the DCM Compiler. The compiler will perform extensive inference — filling in the gaps, reconstructing space-time and trajectories of moving objects, like connecting the dots into a smooth curve — and will produce an internal representation of the TRADE construal.

If the description we have provided is incomplete or contains contradictions (errors), the compiler will not be able to generate that output, indicating that the construal itself is invalid.

In the construal we have built, however, we do have a coherent description of the TRADE, allowing the compiler to generate the full form out of the fragments we provided.

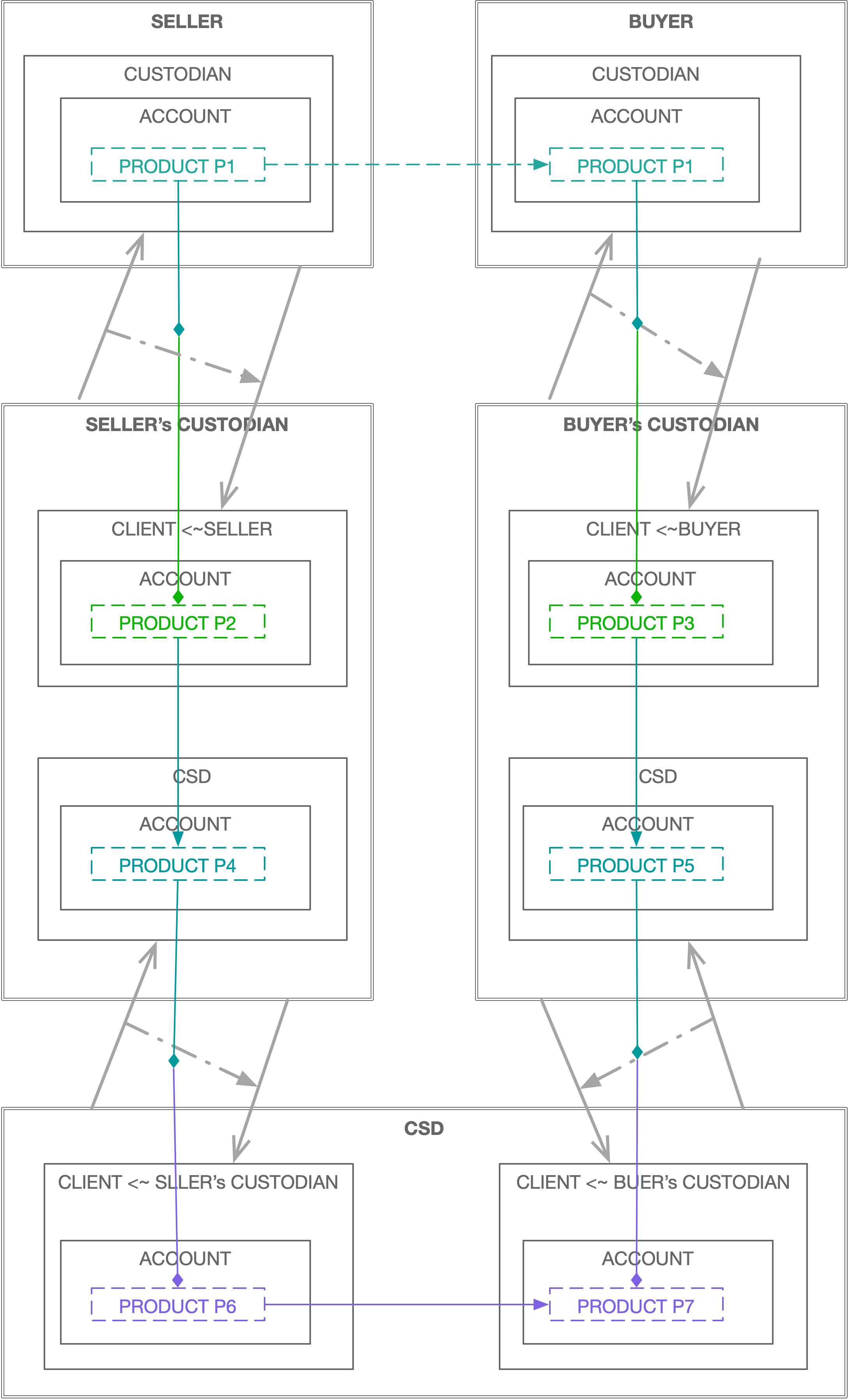

Part of the output generated includes the action plan for each agent involved. Because different agents participate in different contracts, there will be a specific set of contracts associated with each agent — outlining that agent’s contractual obligations.

In our TRADE example, the BUYER and SELLER agents must be aware of the TRADE contract by definition, since both are defined within the TRADE frame. However, the BUYER’s CUSTODIAN, for example, does not need to be aware of the existence of the TRADE contract. Its involvement in executing the TRADE (i.e., the settlement) will be fully governed by its CUSTODY contract.

TRADE contact at different levels of reality

This is an example of instantiating a frame to the runtime level of reality — the definitive or terminal level in the path from abstract/schematic to concrete/specific.

In any non-trivial case, we will have multiple levels of reality embedded within one another, like a Russian doll — where a more abstract level is embedded into a more concrete one. For example:

RELEASE is embedded into MOV_SYNC

MOV_SYNC is embedded into EXCHANGE

EXCHANGE is embedded into TRADE

TRADE is contextualized with many other frames to form a specific construal, which itself is eventually embedded into the runtime level of reality when an actual trade made at the exchange is settled.

Another important point is that everything we have done so far does not deal with actual parties in the real world, but rather with agential roles in a frame — which are abstract. In other words, the TRADE frame describes the type of contract, not an instance of a contract.

When a trade is generated by an exchange — by matching orders from both sides — we obtain an instance of a TRADE contract. At this point, the trade at the exchange must specify concrete values for all the relevant coordinates of the TRADE frame that are required to instantiate it — for example:

binding the BUYER agent to an actual party (e.g., a company that is buying or selling),

resolving the product being traded into a concrete stock (e.g., by specifying an ISIN and quantity),

and possibly inferring the settlement date from the trade date, among others.

It is important to note that whether something is "abstract" or "concrete" depends entirely on the point of view (POV). These are simply two poles of a relation. This is yet another example of a relational concept that often gets mis-objectified — where terms like abstract or instance begin to be used as if they refer to stand-alone entities, rather than representing only one side of a relation.

The binding of a frame's coordinates to runtime values creates a runtime instance of the frame. However, this process does not only happen at a single moment when the frame is first instantiated. Rather, instantiation is a process that stretches over time — because a frame spans a temporal dimension and is durative. As different actions unfold over time, different coordinates may need to be fixed at different points in time.

Compare this to the simplistic concept of instantiating a class in programming languages like Java, which illustrates that the latter represent static things rather than dynamic processes, as discussed in more detail in the section comparing PL with DCM.

Thus, the initial instantiation of a contract like TRADE might not include all the information required to execute it through to completion. Instead, it contains sufficient information to start execution, while other required details can be resolved later — either because they are not yet known at the time execution begins, or because they are not yet needed and can be deferred (resolved on demand).

We provide only a brief sketch of this topic here, without going into detail, as the aim is to focus on the concrete example rather than the theory, which requires separate treatment.

Now, the DCM compiler can automatically generate all the actions for all agents, which, once executed, will result in a distributed settlement of a trade without requiring any additional coding or effort.

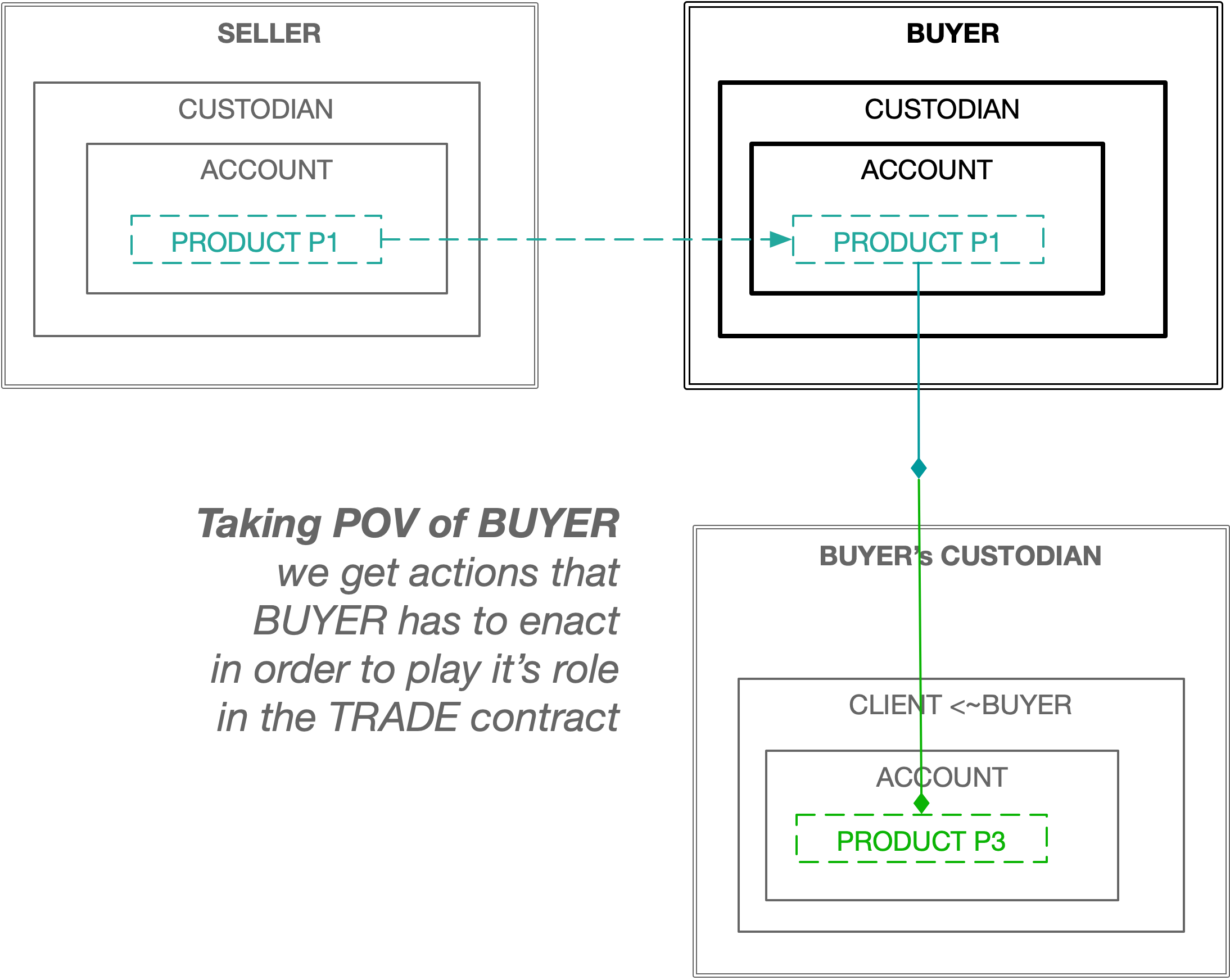

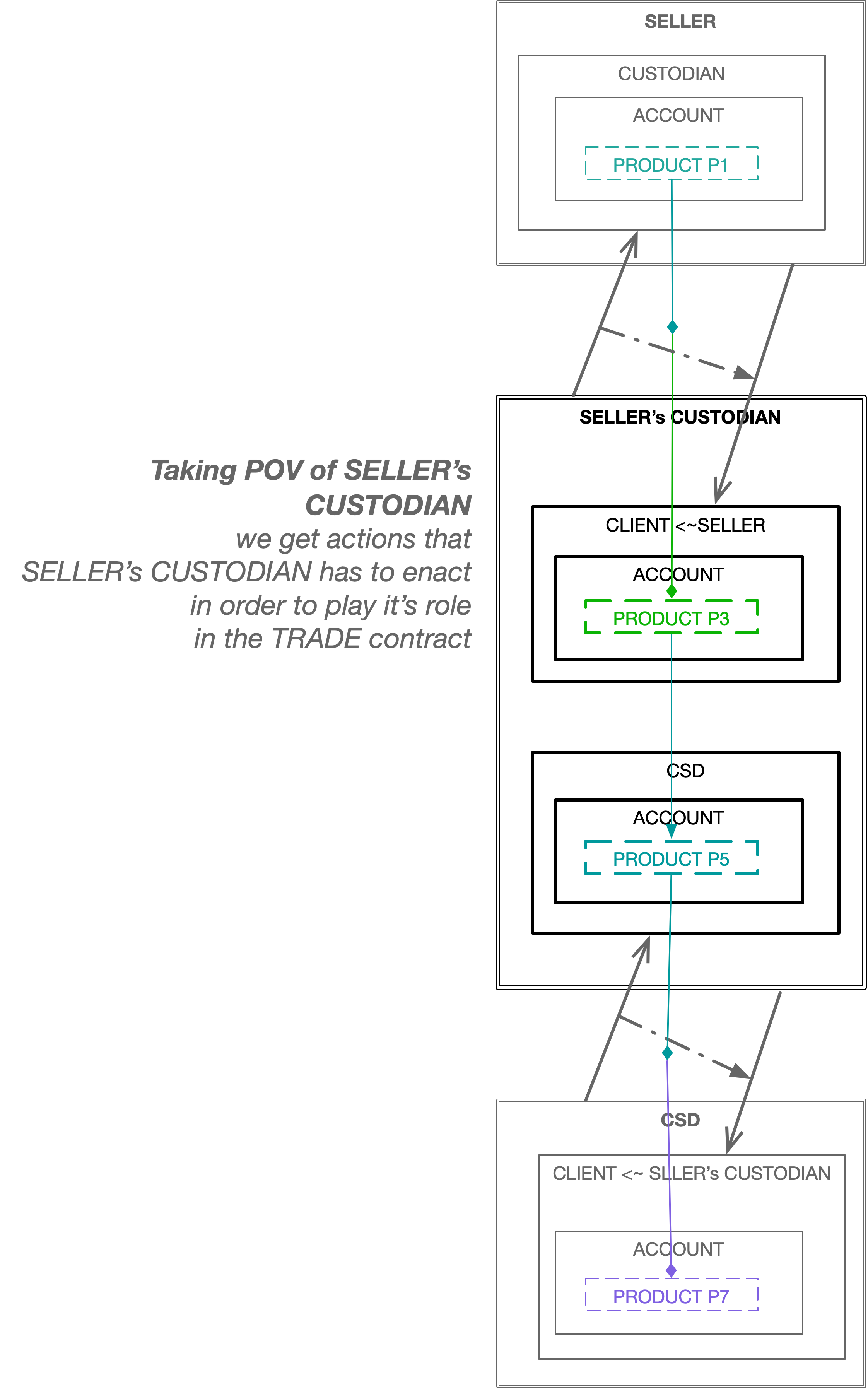

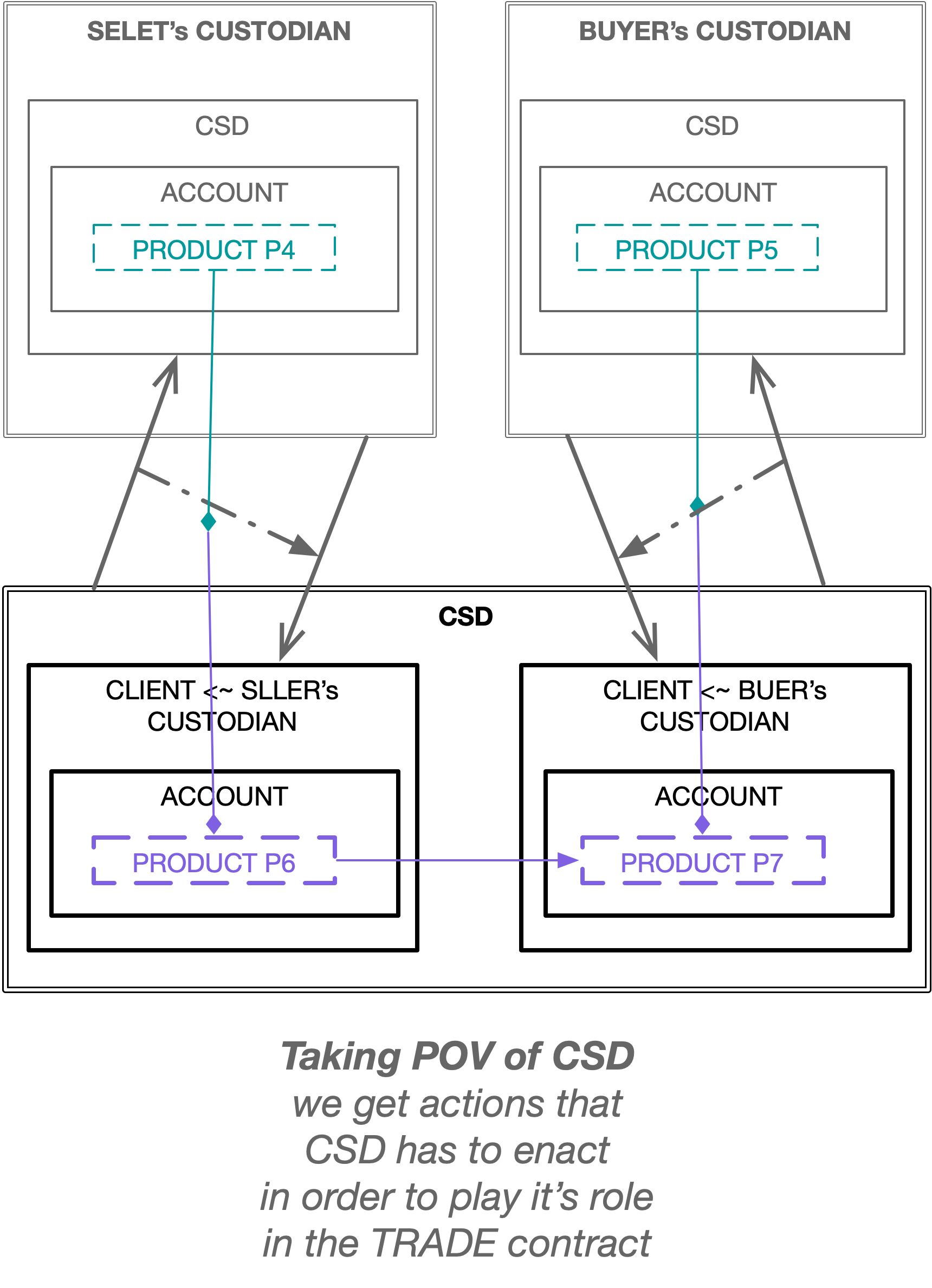

Just as framing is, in essence, adopting a certain POV (as formally described in Frame-Vantage Theory, which will be addressed separately), so is action generation.

To derive which actions each party should execute in order to fulfill its roles in all the frames where it appears as an agent, we need to adopt the POV of that agent in each frame.

Here, we outline the action plan for a few parties involved at different levels of the construal in making the settlement happen. The actual output generated by the DCM compiler includes a plan for each agent involved.

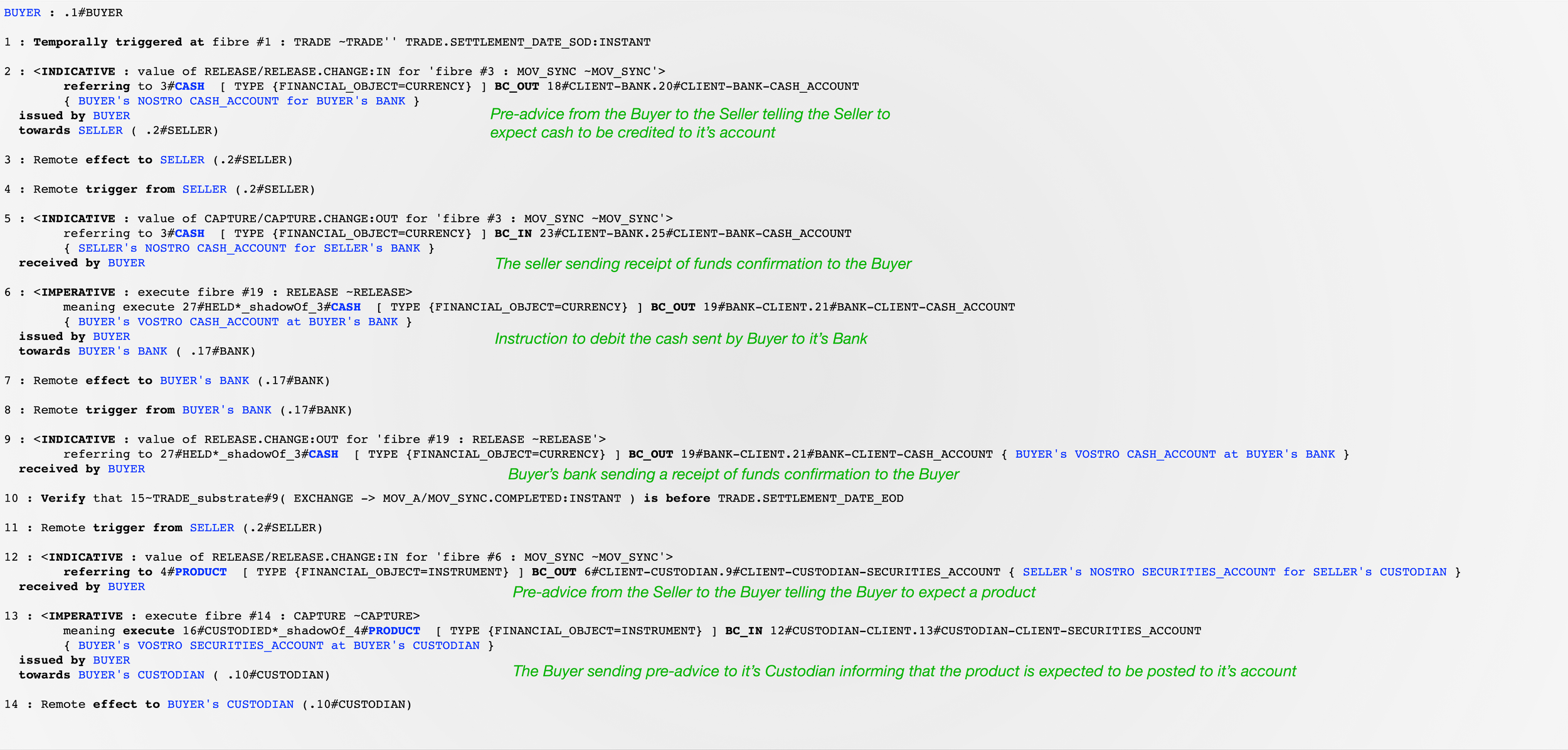

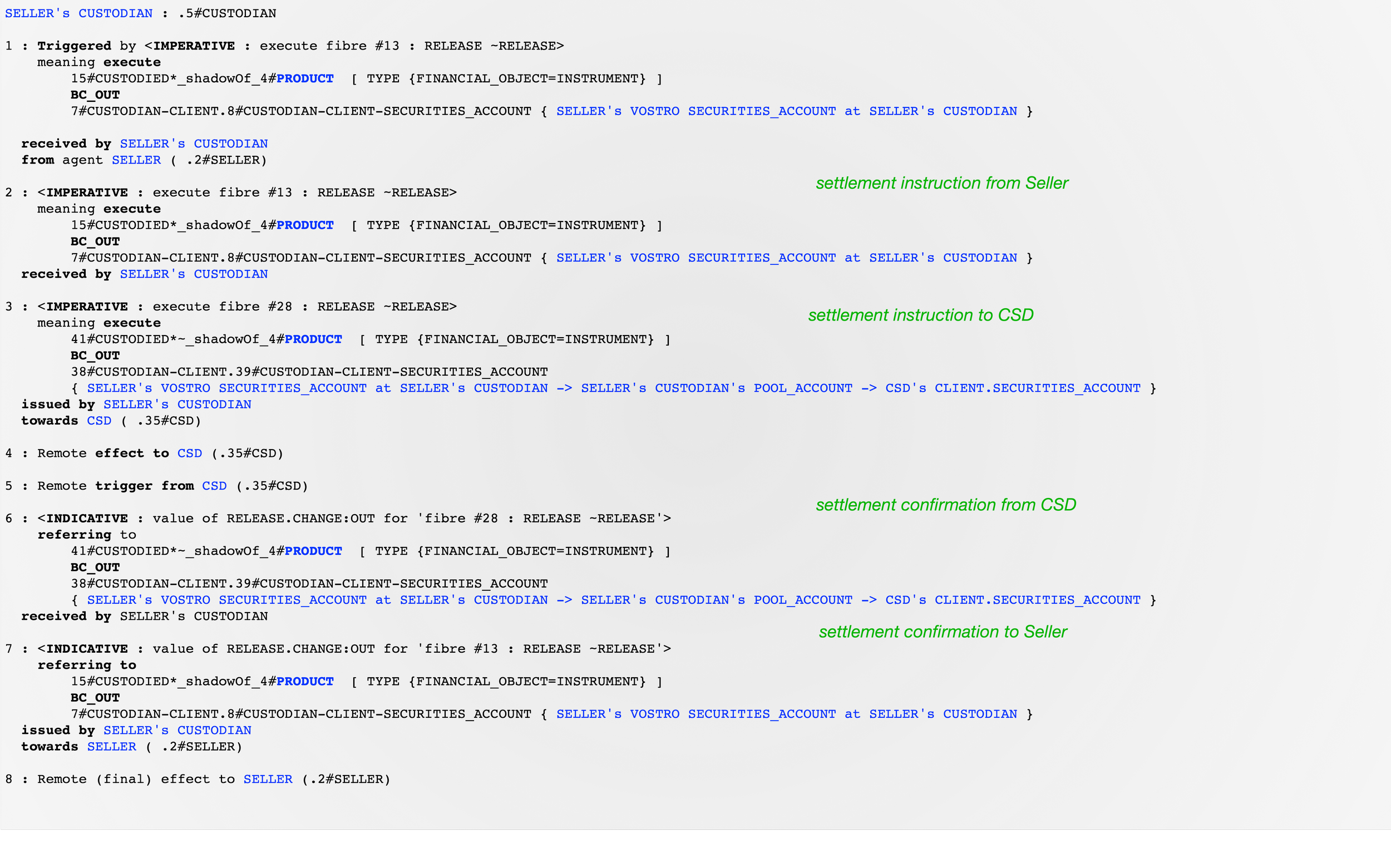

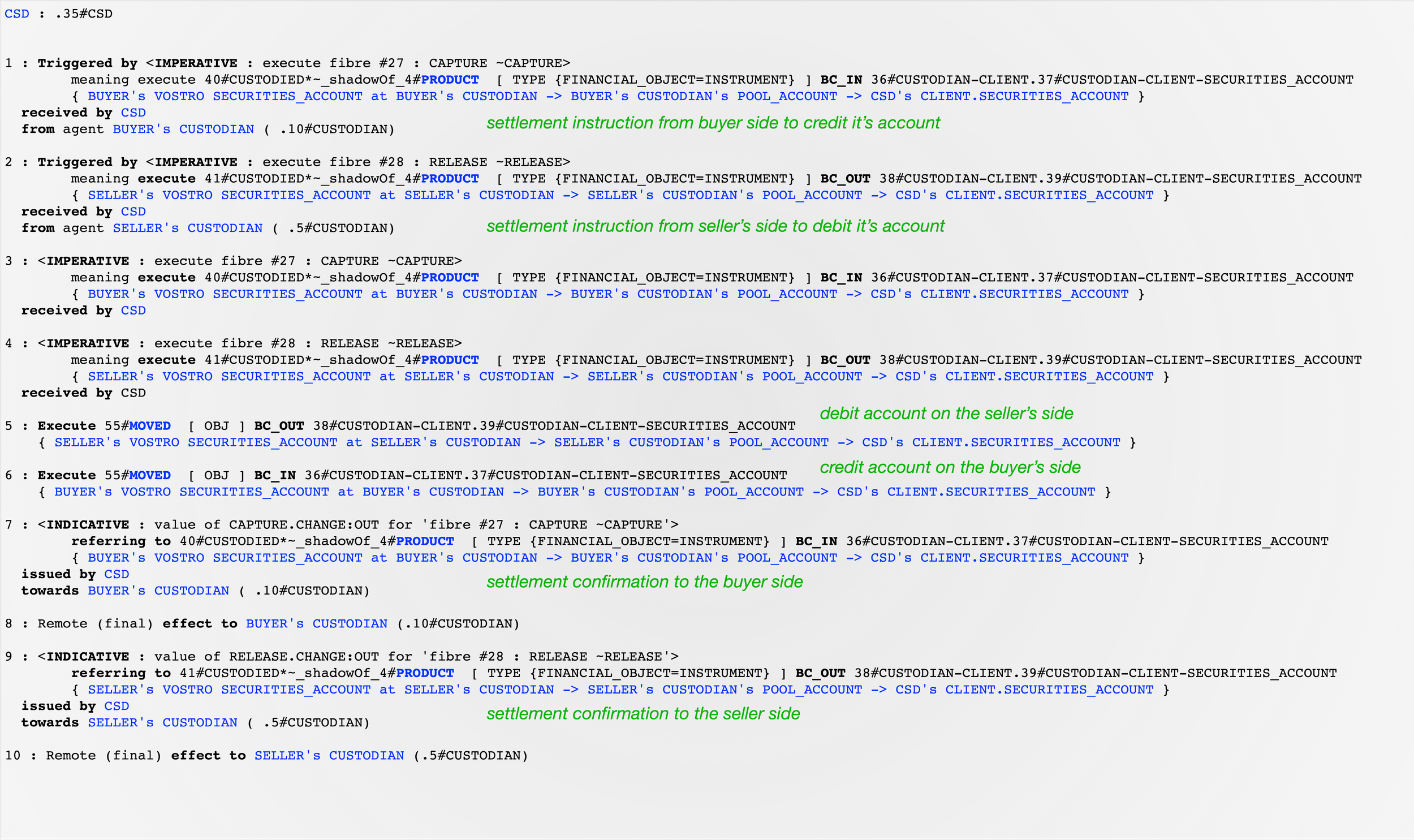

The target domain interpretation is highlighted in green next to each action step in the action plan specification that DCM generated for the TRADE contract.

Generating an execution plan for the settlement

Actions of a BUYER

Actions of a CUSTODIAN

Actions of a CSD

Also note how we ended up with a specification capable of executing a distributed settlement of a trade without writing a single line of programming language code. There are no variables being read from or written to, no function or subroutine calls, no database tables or queries, no data flow diagrams, no coding of sending or receiving messages, no message schemas and registries etc.

This is exactly the point of the example: to show that problems in contract management domains such as post-trade processing—where frames like TRADE and CUSTODY are central—can be addressed purely on the level of cognitive modelling, without dealing with "low level" technical artifacts typically imposed by programming languages (or "low code" platforms for that matter).

The encoding we obtained in the form of DCM source code is therefore almost one-to-one and stands in a modelling relation to the target domain (trade processing). In terms of domain overlap, our goal was to preserve the maximum relevant semantics of the target domain—retaining its inherent information—while adding minimal noise (i.e. avoiding technical idiosyncrasies and irrelevant semantics).

Notice how DCM, despite knowing nothing specific about the domain of trading, generates logic that maps one-to-one onto the trading domain—for example, how sending an imperative command to execute a release of a figure with the nominal construal of cash from a certain location translates to a debit instruction sent to a bank.

DCM already generates human-readable interpretations of locations by using terms like VOSTRO and NOSTRO—domain-specific labels for a very general spatial topology that appears whenever two agents interact and must represent each other.

To sum up, we started with a set of contracts established between different parties. Contracts are essentially commitments to execute certain actions in the future, specified for a particular role that a given party undertakes. A CUSTODY contract engages the party “ABC Trading” as a CLIENT, while another contract, TRADE, engages the same party as a BUYER, and so on.

If each party plays its role in each contract, then each contract is enacted in a distributed manner. Thus, the overall orchestration — such as that required for settling a TRADE — is a direct inference from a set of interlinked contracts.

There is nothing that IT systems need to know beyond the DCM specifications of these contracts in order to execute them.